- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Frisian verbal inflection is dependent on the type of verb involved. The main distinction is between regular inflection (the so-called weak verbs) and irregular inflection. Regular verbs keep their stem intact; the expression of features like tense and agreement is solely done by way of suffixation. With irregular verbs we typically observe stem alternations. For tradionally strong verbs this is the way of marking the preterite, for instance.

Within the Germanic languages, Frisian is rather peculiar in that it has two weak classes at its disposal. What is traditionally called class I has an infinitive ending -e, where the infinitives of class II show the suffix -je. The paradigm of class I resembles the weak verbs of related languages. For instance, it has a preterite suffix with a dental consonant, in the Frisian case -de or -te. The paradigm of class II is rather different. The distribution of the two classes seems mainly a matter of accident. However, at least one phonological and morphological dependency may be observed. Verbs with a stem ending in a schwa plus sonorant are always je-verbs, e.g. timmer-je to hammer. Also, verbs that are built by way of conversion heavily tend to be a member of class II. Thus from the noun keal calf we can derive keal-je to calve, and the adjective koel cool may thus result in kuol-je to cool.

Membership of a class is not always stable over time. There is a natural pressure to give up irregularity. Transition into the opposite direction is rare, but does occur. Influence of Dutch also causes a switch of the weak class II to class I.

Frisian not only has two classes of weak verbs at its disposition, but in addition there is a great deal of variability within them. This is due to dialectical differences, residues of older forms and effects of phonological processes. We also see interparadigmatic crossovers, in that certain suffixes may show up in another class. Special sections have been devoted to remarkable forms for the second person singular and the imperative.

Frisian has two classes of weak verbs at its disposal. Class I is commonly referred to by its infinitive, whichs ends in the suffix -e, hence the name e-verbs. It resembles closely the system that may be found in other Germanic languages like Dutch, German and English. Its main characteristic is the formation of the past thense, which is by way of a dental suffix, i.e. -de or -te in the singular. Also the suffix of the past participle is dental: -d or -t.

The second class of Frisian weak verbs behaves very differently. Conspicuous is the infinitival ending -je, hence this class is commonly referred to as je-verbs. The ending returns in the present tense in first person singular, in the plural and in the imperative. The second and third person singular also show a schwa. This has the effect that the suffixation in the present singular builds an extra syllable, which is not the case in Class II. The suffix of the past tense stands out in that it lacks a dental ( /d/ or /t/). This, however, is a feature of Modern West Frisian, where Old Frisian /d/ was deleted (see Meijering (1980)). As is mentioned in the section on Weak verb classes in East and North Frisian below, the situation in East- and North Frisian dialects can be different.

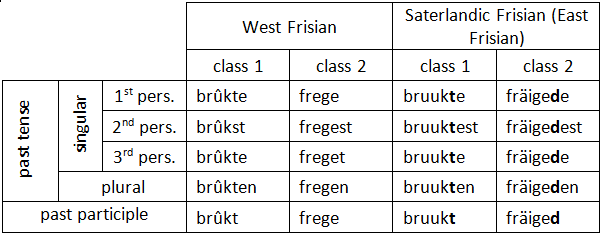

The Old Frisian two-class-system of weak verbs with its infinitive endings in -a and -ia, occurs in West Frisian as two classes of -e and -je. In East Frisian and North Frisian, it has been preserved differently throughout the varieties. Bosse (2013:7-25) gives a detailed overview of the different developments. The only variety of East Frisian left today, Saterlandic Frisian, preserved the system just like West Frisian did, with the single exception that the -je class did not lose its dental in past tense and past participle (table according to Bosse (2013)):

Inflection of brûke/bruke to use; to need and freegje/fräigje to ask

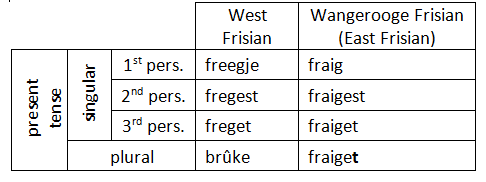

The extinct variety of the island Wangerooge had two weak verb classes as well, but its distribution differs from that of the Old Frisian system and is only phonologically based (see Bosse (2012), Bosse (2013) and Versloot (2001:428-429)).

The North Frisian varieties preserved the system in Insular North Frisian, though phonologically different. Due to schwa apocope in Island North Frisian, Old Frisian -a became Ø (null morpheme), while Old Frisian -ja became [ɪ] (-e or -i, spelled differently) in the variety of the islands Föhr, Amrum and Sylt and [ә] in the variety of the island Heligoland. The dental in past tense and past participle has been preserved, too.

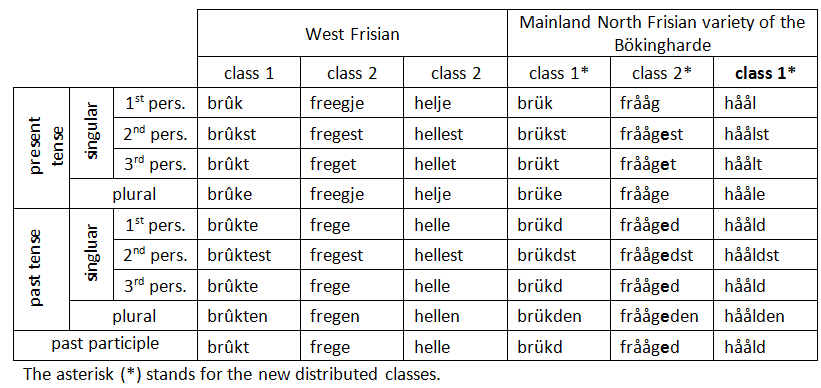

As Bosse (2013:16-24) shows, the Mainland North Frisian varieties can be separated into a (now mostly extinct) southern part (the Südergoesharde and the Mittelgoesharde) which preserved the Old Frisian two-class-system, and a northern one (the Halligen, the Norderdoesharde and everything north of it) which reorganized the distribution on a phonological basis and distinguishes two classes, based on the ending of the verb's stem. If the verb stem ends with a sonorant or a vowel, there won't be any vowel between verb stem and inflectional suffix (class 1*), whereas there will be an -e- in all other cases (class 2*). See Hoekstra (2001:778) for a brief overview. As there are exceptions from this rule (see brüke in the table below which won't fit in the schema), Bosse suggests that there could be some relics of the old distribution of classes Bosse (2013:20).

Inflection of brûke/brüke to use; to need, freegje/frååge to ask and helje/hååle to fetch

The reason for this system of distribution (Insular North Frisian and southern Mainland vs. northern Mainland North Frisian) is not quite clear, yet. Bosse sees a possible explanation in schwa apocope, which basically also took place in the variety of Mittelgoesharde and might have forced a development similar to that on the islands. The variety of the Südergoesharde might hence have been isolated from the developments in the north. There might as well have been other factors, see Bosse (2013) for a detailed analysis.

The Old Frisian plural ending -ath in present tense has been replaced in all Frisian varieties by an ending -e (or apocope where it took place). Only the varieties of Wangerooge and the Südergoesharde have both kept an ending -(e/i)t:

Inflection of freegje/fräigje to ask

Hoekstra (2001:778-779) assumes a supportive influence from neighboring Low German varieties, which also have got a plural ending -t in present tense.

[This extra is written by Hauke Heyen (Kiel)]

In general, it is hard to tell beforehand which verbal stem takes which suffix, -e or -je. Both classes already existed in the Old Frisian period, with the corresponding endings -a and -ia. In general, it seems that the membership of a class remains relatively stable over time. Thus Old Frisian sitta to sit is sitte nowadays, and Old Frisian folgia to follow is modern folgje. There are exceptions, however. So libje to live nowadays belongs to class II, but in Old Frisian the verb was libba and hence belonged to class I. The Renaissance poet Gysbert Japicx had relatively often je-verbs where these nowadays belong to class I. Examples are bruwckje to use, nowadays brûke, or rêstje to rest, which is modern rêste.

Both classes can be found in all dialects. Some individual verbs have dialectical variants, but it is hard to discern a pattern in the facts. Possibly, there is a slight tendency that -je can be found more often in the south. Examples are the verb passe to fit, which is pasje in the deep southwest, and northern damme to play checkers vs. southern damje.

Despite these uncertainties, there is a phonological criterion that does not allow exceptions. If a stem ends in a syllable that contains a schwa, then it unequivocally opts for class II. Examples are skarrelje to rummage, hoffenje to clean, timmerje to hammer and itigje to calibrate.

There is also a morphological generalization. Conversions of other lexical categories to verbs heavily tend to result in a verb belonging to class II. Thus the adjective grien green becomes grienje make/become green, the noun ferve paint results in fervje to paint. From the cardinal number ien one we can build ienje to bring at one, i.e. to thin out (of sugar beets) and from the now obsolete interjection moart we still have the verb moartsje to yell. Of course, in many cases this morphological generalization combines with the phonological rule. All such products of conversion probably contribute to the fact that the majority of the Frisian verbs belong to class II.

The existence of the two classes can sometimes bring about semantic differences. For instance, the verb hurde to bear, stand is opposed to hurdzje to harden. And the verb sichte to determine the height of an unknown point on the basis of two others is semantically different from sichtsje to cut down with a sickle.

Some information about the two classes in older stages of the language may be found in Tamminga (1963:142-145). He also mentions the effect of conversion. The existence of southern je-varieties of the verbs brûze to foam, sûze to rustle and a few others with the same rhyme are mentioned in Hof (1933:20).

Weak verbs of class I obey the following paradigm. First the schema of the finite forms is given:

| Tense | Number | Person | Ending |

| present | |||

| SG | |||

| 1 | - | ||

| 2 | -st | ||

| 2 polite | -e | ||

| 3 | -t | ||

| PL | |||

| 1 | -e | ||

| 2 | -e | ||

| 3 | -e | ||

| past | |||

| SG | |||

| 1 | -de/-te | ||

| 2 | -dest/-test | ||

| 2 polite | -den/-ten | ||

| 3 | -de | ||

| PL | |||

| 1 | -den/-ten | ||

| 2 | -den/-ten | ||

| 3 | -den/-ten |

Note that the endings of the past tense actually consist of two suffixes. Firstly, we have -de or -te indicating the past tense, and secondly there are the agreement suffixes, zero -∅, and -st and -en. Furthermore, it has to be mentioned that the polite pronoun jo you is semantically singular, but that it takes plural verbal morphology.

The non-finite forms, the past and present participle, both forms of the infinitive, and the imperative, are as follows:

| Category | Subcategory | Ending |

| participle | ||

| present | -end(e) | |

| past | -d/-t | |

| infinitive | ||

| I | -e | |

| II | -en | |

| imperative | - |

To be a bit more concrete, see the following forms of the verb wenne get used to (which will be contrasted below with the class II verb wenje to live). First the present tense:

Here are examples with the past tense:

Finally, examples of the non-finite forms:

The paradigm of class I gives two possibilities for the suffix of the preterite, and also for the past participle, viz. a form with /d/ or /t/. The choice fully depends on the voicing of the final segment of the stem. If this is voiceless, i.e. ending in /p/, /t/, /k/, /f/, /s/ or /x/, then the first element of the suffix is also voiceless, hence with a /t/. This results in the suffixes -te(n) for the finite forms and -t for the past participle. If by suffixation two identical segments follow each other, then by degemination only one of them is actually heard. Thus if for example of the verb sette to set the stem set [sɛt] combines with the past tense ending -te, then the result is [sɛtə], pronounced with a single [t].

Some general orthographic conventions also apply to the spelling of verbs. In stems with short vowels, we have a doubling of the following single consonant, for instance wy wenne we get used to in the examples above. Long vowels in the stem are doubled in a closed syllable, and get a single notation if the syllable is open. For instance, we have ik praat I talk vs. wy prate we talk. The suffixes of the past tense are simply added to the stem, without change in the orthography. Stems with a long vowel followed by a single consonant consisting of <d> or <t> ar an exception. In this case, this consonant remains single after adding the suffix. So we have the form wy praten we talk.PRET we talked. This is different from Dutch, which explicitely reflects the addition of the suffix to the stem in the spelling. Hence, in Dutch we have the spelling wij praatten, although the meaning and the pronunciation compared to Frisian wy praten is exactly the same. On this issue, Dutch orthography takes a morphological stand, where Frisian has a phonological position. The Frisian solution is in line with other instances where the last segment of the stem and the initial consonant of the suffix are identical. Hence, of the verb passe to fit we have the second person singular present tense do past, and not *passt. Also, it is not hy *sitt, but hy sit he sits.

Knop (1954:243-247) reports that the first segment of the preterite suffix -de(n) may delete after stems consisting of a long vowel which is followed by a consonant. The deletion is more often found in the singular affix -de than in plural -den. So we get forms like dele (cf. standard Frisian deelde parted), keare (cf. standard kearde turned) and klime (cf. standard kliemde stained).

Weak verbs of class II follow the following paradigm. Again, the finite forms are presented first.

| Tense | Number | Person | Ending |

| present | |||

| SG | |||

| 1 | -je | ||

| 2 | -est | ||

| 2 polite | -je | ||

| 3 | -et | ||

| PL | |||

| 1 | -je | ||

| 2 | -je | ||

| 3 | -je | ||

| past | |||

| SG | |||

| 1 | -e | ||

| 2 | -est | ||

| 2 polite | -en | ||

| 3 | -e | ||

| PL | |||

| 1 | -en | ||

| 2 | -en | ||

| 3 | -en |

The non-finite forms of the verbs of class II are suffixed as follows:

| Category | Subcategory | Ending |

| participle | ||

| present | -jend(e) | |

| past | -e | |

| infinitive | ||

| I | -je | |

| II | -jen | |

| imperative | -je |

The difference in suffixation between class I and II would reduce significantly if it was assumed that class II contains a thematic element, consisting of -j(e)- or -e-. For instance, an abridged present tense singular would then be -je- ø, -e-st and -e-t. The present plural would be -j-e . This array of (final) suffixes thus boils down to ø-st-t-e, which is exactly the same as the set displayed in class I. A suggestion by Jarich Hoekstra for such an analysis is mentioned in Werner (1992:183) and slightly elaborated in Hoekstra (2001:90-91). See also Werner (1993).

For concreteness' sake, full forms are presented below, and in order to compare optimally with class I, these will be instances of the verb wenje to live (reside). First, the forms in the present tense:

Likewise the past tense of class II verbs:

Finally, the non-finite forms of class II:

Also in this class the usual orthographic rules apply. See the doubling of a consonant after a short vowel, as in wenne. Or the double spelling of a long vowel in a closed syllable, as in traapje to kick, which shifts to a single spelling in an open syllable, as in (ik) trape (I) kicked.

The Frisian dialect of the island of Schiermonnikoog shows a unique difference from the standard pattern of the paradigm of je-verbs. In the third person of the present tense, the /t/ of the suffix -et is lacking. Thus of the verb winje to live we get he wene he lives. This is probably a feature that had a wider spread once than it has today. Hof (1919) notices that it also occurs in a collection of proverbs dating from the middle of the 16th century. Its author Reyner Bogerman originated from the Dongeradielen, the part of the mainland directly opposite to the island. A comparable phenomenon is the loss of -t in a few irregular verbs.

In Old Frisian the preterite and the past participle showed a /d/ in the suffix (see Bremmer (2009:80)). For instance, of the classical Old Frisian verb folgia to follow the respective forms were folgade follow.PRET.SG followed and folgad follow.PP followed. Later we see a reduction of the vowel /a/ to schwa, and already at the end of the Middle Ages the /d/ of the preterit tends to get lost. Soon after, the participle followed, but in the peripheral Frisian dialects a residue of the old situation may still be found, although this is restricted to the participle. For the historical process, see Meijering (1980).

The dental is still alive verbally in the grammar of the Frisian dialects of the island of Skylge (Terschelling). According to Knop (1954:242), the suffix of the past participle in these dialects is -ed. Hence forms like kleaged complained and korted shortened. We find the same ending -d in the dialect of Schiermonnikoog, but here it is restricted to past participles used attributively. Among others, Fokkema (1969:24) gives the following examples:

Likewise as on the island of Schiermonnikoog, in the dialect of Hindeloopen the suffix -ed is only found if the participle is used as an adjective. Examples like in lobbeden hûnd a castrated dog or in wyteden moere a whitened wall have been encountered, but nowadays, the suffix is obsolete. Within the written inheritance of the dialect, its greatest spread is in the form of nominalized pseudo-participles, indicating the various patterns of textile for the tradional costume of the small town. Hence assignments as aig-ed-e eye.PP.NOM pattern with eyes or raa-ryng-ed-e red-ring-PP-NOM pattern with red rings. See for this pattern in the part on synthetic compounds.

Superficially, it seems that old forms with /d/ even may be found in the past tense. In the western dialect of the island of Terschelling forms like maked made, drigede threatened, sâltede salted have been encountered. Jongkind and Van Reenen (2006:120-121) suppose, however, that these are not old but rather younger forms, to be analysed as a reinforcement of the past tense by borrowing the past tense suffix of the paradigm of class I. In an older description of the dialect, Knop (1954), such forms fail altogether.

The verbs of class II with a stem ending in /d/ or /t/, respectively, show the insertion of a /z/ and an /s/, thereby respecting the [+/- voice] of the stem. Note that the sibilant only shows up before -je. We thus have an infinitive wedzje to bet, and subsequently also forms like ik wedzje I bet, hja wedzje they bet and wedzjende bet.PRS.PTCP betting. An example with a stem ending in /t/ is rotsje to rotten, with comparable inflectional forms. Hence, the present tense of a verb like fetsje to grasp is as follows:

The original phonological change, the insertion of a sibilant between /d/ or /t/ and /j/, took place in the 18th century, but it did not affect the peripheral dialects of Hylpen (Hindeloopen), Skiermûntseach (Schiermonnikoog) and the eastern dialect of the island of Skylge (Terschelling). There the clusters /djə/ and /tjə/ remained intact. In the western Frisian dialect of Skylge this assibilation did occur, however, with the subsequent loss of /j/ (which can also be observed in diminutives). In Westerschelling we thus have forms like fetse to grasp and wedze to bet, which are fetsje and wedzje in standard Frisian. In contrast, we encounter the forms fatje and wedje on the island of Schiermonnikoog, representing one of the three dialects that were not affected by the assibilation.

However, also in the Frisian heartland this insertion does not occur in the particular phonological context after a stem final consonant cluster -st. At least, superficially this seems to be the case. So we have a verb which is spelled treastje to comfort, and not *treastsje. The stem of this verb is treat. Other examples are ferwoastje to destroy, dwêstje to extinguish, fertoarstje to have a thirst and kostje to cost. In order to see what is really going on here, we have to take as closer look at the pronunciation. The last example kostje is pronounced as [kɔsjə]. This surface form is best explained if we assume that insertion of /s/ really took place. This would yield a form /kɔstsjə/. A rule of t-deletion in the context /sts/ would result in the sequence /ss/, which after degemination becomes the single /s/ of /kɔsjə/. In some verbs, and for some speakers, such a form may be the impetus to reanalyze the stem in its entirety. We can then come across forms like the third person singular present tense kosset /kɔsət/ or the past participle kosse /kɔsə/. Such a reanalysis seems to be restricted to verbs with a relative high frequency. A form like [trIəsət] for treasted does not occur. Moreover, the reanalysis is not reflected in the spelling, which always retains <t> here.

The phonological exception on the insertion of /s/ is analyzed in Visser (1993). He also points to the effect that speakers try to compensate for the decrease of transparency of the stem. This can be done by taking recourse to the paradigm of the weak verbs of class I. Here Visser mentions the infinitive liste, instead of listje to frame. Another strategy might be the insertion of an augment -(i)g-. We then get verbs like hastigje to hasten (instead of haastje, with shortening) or dwêstgje to extinguish instead of dwêstje.

In the unmarked case, it could be expected that the stem remains intact throughout the paradigm. This is not true, however. A process as final devoicing applies automatically. For instance, it affects the first person singular of the present tense and the imperative of class I. Thus a form ryd of the verb ride to ride is phonetically [rit]. Assimilation applies in the third person rydt, which is also pronounced as [rit]. With respect to the second person, the final segment even deletes, as a consequence of t-deletion before -st. The form rydst then becomes [rist].

In the dialect of the island of Schiermonnikoog we see an interesting allomorphy on the edge of the stem of class I verbs and the suffixes of the past tense and the past participle. In this dialect, clusters of /r/ plus /d/ turn to /z/ (with a hypothetical historical intermediate stage /dz/). In the past tense, this resulted in a form ik hieze I rented (from ik hierde). In combination with final devoicing, the past participle became hies rented, derived from the form hierd. Later, the full form of the suffix became reintroduced in order to make the paradigm of class I more regular, with /z/ remaining, however. Most speakers nowadays say ik hiesde and hiesd.

For this change see Dyk (2006).

With respect to vowels, we only rarely find effects of breaking and shortening. Although widely available in the verbal paradigm of class II, we never see these processes effected in their canonical context, i.e. theaddition of a syllable. Quite marginally, we see these changes operating before consonant clusters, typically occurring in the paradigm of class I. The only verb that shows traces of breaking is sliepe to sleep. Thus for several speakers, the three persons of the present tense are sliep sleep.1SG.PRS [sli.əp], sliepst sleep.2SG.PRS [sljIpst] and sliept 3SG.PRS [sljIpt]. Hence, the second and third person are broken before the clusters [pst] and [pt], respectively. In the same way, the forms of the past tense and the past participle are broken; in all these cases, we see a cluster [pt]. Historically, in other dialects this verb has been affected by shortening, see strong and other irregular verbs.

Synchronically, shortening occurs in the same paradigmatic contexts in the area of Dongeradiel, which geographically is in the far northeast of the language area. As far as is known, this only takes place in stems ending in a voiceless stop. So, with the verb slepe to drag we have the regular first person singular ik sleep I drag in the present tense. But shortened forms are do slipste you (SG) drag, hy slipt he drags, ik slipte I dragged and ik haw slipt I have dragged. Other verbs that show this behaviour are for example slope to demolish /slo:pə/, smoke to smoke /smo:kə/ and stoke to heat /sto:kə/. In the dialect of the neighboring island of Schiermonnikoog the same kind of shortening occurs, again with long stems ending in /p/ or /k/. Correspondingly, the shortening vowels in that dialect are /e:/ and /ø:/ (original /o:/ has been fronted). One might therefore tentatively conclude that only mid vowels are involved in this type of shortening. The driving force seems to be a complex consonant cluster. That will be the reason why we only find it with the voiceless stops /p/ and /k/, and not with their sibling /t/. After suffixation the final /t/ of the stem deletes by degemination (for the suffixes -t and -te)n) or t-deletion before the suffix -st. In this case we do not get a complex cluster.

The shortenings in the Dongeradiel dialect are observed in Hoekstra (1990). The shortening on the island of Schiermonnikoog is shortly dealt with in Fokkema (1969:35-36). Shortening also took place historically. It left its traces in a few irregular verbs.

The dialect of Schiermonnikoog also shows the opposite of shortening, i.e. lengthening, and this even on a much larger scale. Lengthening occurs in class II with stems having a short vowel when followed by one consonant, and if this stem is followed by a suffix beginning with a schwa. In that case, the stem vowel is in an open syllable, which is a condition for lengthening. As an illustration, take the verb winje to live, which is pronounced as [vInjə]. The present tense singular forms are: ik winje - dò weneste - hy wene. In the first person form winje we have a closed syllable, and the vowel remains short. In weneste and wene an open syllable is created, with subsequent lengthening to /e:/. It should be noted, however, that not all potential candidate verbs are affected by the process.

More on this type of lengthening in Fokkema (1969:38-40) and Visser and Dyk (2002:xxxvi).

Stems with a final syllable having a schwa as nucleus always belong to class II. In this class, various inflectional suffixes also contain a schwa. The schwa of the suffixes -est and -et may delete, then, which has the effect that a sequence of two schwa syllables is avoided and, hence, that the verbal form has one syllable less. As an example, do stammerest you.SG stammer.2SG.PRES turns to do stammerst, and hy stammeret he stammers becomes hy stammert. There is a restriction on this process, however. For the second person of the verbs of class II, the form of the present and past tense are similar: both are stammerest. Now, it appears that schwa-deletion only takes place in the present tense. Here is an example with the verb tekenje to draw that illuminates the contrast:

We thus see that this type of schwa deletion is used to discriminate between tenses.

This section is based on Hoekstra (1988).

Frisian has more than one paradigm for verbal inflection. Apparently, this circumstance may be used to make certain endings, or certain cells in the verbal paradigm, more transparent. It seems that certain suffixes are taken over from one of the other paradigms. Two cases may be relevant for such an analysis, one in the realm of past participles, and the other with respect to the form of the third person singular of the present tense.

Past participles of the verbs of class I end in /d/ or /t/, dependent on the final segment of the stem being voiced or voiceless. By final devoicing, /d/ turns to voiceless [t]. If, however, the stem of the verb itself ends in /d/ or /t/, then the phonetic effect is that the addition of the suffix is not audible. Thus the stem of the verb wjudde to weed is wjud, and the past participle is also spelled wjud; both forms are pronounced as [vjøt]. Likewise with the verb sette to set, which has a stem set and a past participle set, both pronounced as [sɛt]. Note that in Frisian both forms, in contrast to languages like Dutch and German, are not differentiated by the participial prefix ge-.

Apparently in order to distinguish the form of the participle, one may observe a tendency to add a suffix -en after the stem, yielding participles like wjudden weeded and setten set. It is quite probable that this ending is "loaned" from the paradigm of the strong verbs, where the standard ending of the past participle is likewise -en. This change is still going on: the addition of -en is more frequent among the younger generation. Its origin must be sought in the southwest. Dialect maps indicate that the change is already complete there. It is spreading to the northeast, where the result is variable at best, depending on the individual lexical item. There are even indications that verbs of class II are also vulnerable for the change. We then get participles like oppotten (from oppotsje to pot; to hoard up) or hoeden (from hoedzje to protect). A comparable change took place in the participles of strong verbs.

The phenomenon of the emergence of the ending -en after weak participles was first noticed (and explained) by Hof (1951). Tamminga (1985:90-91) gives several examples of the phenomenon, also from verbs of class II. Data about the dialectological spread and the intergenerational increase can be found in Van der Veen (1980).

As is the case with the participial suffixes -d and -t, verbs of class I with a stem ending in /d/ or /t/ also have problems to audibly express the ending -t of the third person singular of the present tense. This will be the reason that every now and then the insertion of a schwa may be heard, resulting in a suffix -et. The following quotes are from Frisian journalists:

The emphasized forms belong to the verbs melde to inform, betsjutte to mean and bestride to dispute, respectively. These are all class I verbs; according to the standard paradigm, the forms should have been meldt, betsjut and bestriidt. Again, it is quite plausible that the new endings have been "borrowed" from another paradigm, in this case the weak verbs of class II, which also show an ending -et after the stem. This phenomenon is not quite widespread yet. It is mostly restricted to the spoken language.

As can be seen in the paradigms above, the second person singular consists of two forms. These are related to two different pronouns. The unmarked one is do, dialectically also dû. As is also the case in German and in older English, it is always related to a finite verbal form that shows the cluster -st. Next to do there is a polite form jo. It has the remarkable property that it requires a finite verb that is identical to the plural forms of the paradigm, although the semantics of jo itself is singular. Frisian does not have a separate pronoun for a polite second person plural. The plural form jim(me) is applied in all circumstances. Thus jo is not allowed in a fragment like the following:

| Achte bestjoer. Yn jimme brief fan ... | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| dear board. in your.PL letter of ... | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dear members of the board. In your letter of .... | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Although in the paradigms above the ending governed by the subject do is always noted as -st, one may also encounter a longer form, viz. -ste (pronounced as [stə]. This longer form was much more frequent earlier, for instance in the works of the 17th-century poet Gysbert Japix, and it is still the common form in the Frisian dialect of the island of Schiermonnikoog (and, for that matter, also in the mixed Frisian-Dutch dialect of the neighbouring island of Ameland). On the main land its use seems to be variable. Some grammarians prescribe the use of the longer form for the past tense of class II, to distinghuish it from the present tense, which is otherwise identical. Thus the respective present and past forms wennest live.2SG.PRS lives and wennest live.2SG.PRET lived would then become wennest and wenneste, respectively. This is indeed the distribution as reported for the island of Terschelling. However, it seems that reality is more complex on the mainland, and that -ste also occurs in other contexts. Other grammarians indeed support this position; see the literature below.

The restriction to the past tense may be found in Van Blom (1889), Postma and De Clercq (1904) and Popkema (2006). This proposal is criticized in Hoekstra (2013:4-5). Long forms in present ànd past tense are mentioned in Colmjon (1863:89-90), Feitsma (1902:55-56) and Sipma (1913:69). For the forms of Gysbert Japix, see Epkema (1824:lxv-lxxviii). For the dialect of Terschelling: Knop (1954:216). For Schiermonnikoog: Fokkema (1969:33-51). For Ameland: Oud (1987). Hoekstra (1997:79-80) suggests that the origin of the long form should be sought in the addition of a clitical form de of the singular second person pronoun do.

The circumstance that the forms of the present and past tense of the second person singular are identical in class II also seems to have occured with respect to the verbs belonging to class I. At least, this is stated by some grammarians, and sometimes one can also find such forms in older texts. We encounter past tense forms as (in present-day orthography) do mienste you meant, do flokste you cursed or do praatste you talked. Nowadays such forms are obsolete: a dental suffix (-de/-te is always necessary for the present tense of class I.

The similar forms are mentioned in the grammars of Colmjon (1863:89-90), Feitsma (1902:55-56) and Sipma (1913:69), all of them with the common affix -ste. Common -st is mentioned in Sytstra and Hof (1925:149-152). Fokkema (1948) has both forms. Hoekstra (2013:5-6) discusses possible explanations for the emergence of a past tense form without a dental, such as assimilation after an inserted /s/ (in Sytstra and Hof (1925)) and haplology, as in hypothetical -teste>-ste. Maybe the solution should be found in metathesis: -test>-stte>-ste.

A final remark: Frisian finite verbs with singular second person inflection can occur without an accompanying subject. An example is:

| Hast it al sjoen? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| have.2SG.PRES it already seen? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Have you seen it already? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This so-called pro-drop is further dealt with in the part on Frisian syntax.

The form of the imperative of class I is similar to that of the stem whereas in class II the forms of imperative and infinitive are identical. In both cases, the form of the imperative is the same as the form of the first person singular present tense: compare ik pak I take with pak! take! in class I and ik himmelje I clean with himmelje! clean! in class II.

With respect to class II, there are two exceptions to this rule: hark! listen! and wacht! wait!. However, the regular forms harkje! and wachtsje! also exist. What is more, for most speakers the shorter forms only occur if used independently. Compare:

The distribution of these frequently used imperatives suggests that the short forms function as a kind of interjections. The form wacht! wait! might be due to interference of Dutch, but as the verbal stem *hark to listen does not occur in Dutch, interference of that language is no option in this case.

Versloot (2003) gives a global historical development of the forms of the imperative, especially of those of class II. He tentatively suggests that the forms hark and wacht are residues of older forms.

Although it may be the case that the majority of the weak verbs belong to class II, it is this class that is nowadays under a certain pressure. The reason may be the majority language Dutch which lacks such a class. It appears that especially verbs that have a great deal of formal resemblance to a Dutch counterpart run the risk of a transition of class II to class I. A classical example is hoopje to hope that becomes hope. For the record, it is not the case that the Dutch paradigm is taken over in full. For instance, the second person singular present tense of sakje to drop is, instead of do sakkest, then becoming do sakst, comparable to do pakst of the class I verb pakke to take. In the same vein the third person ending -et is vulnerable in that it is at risk to turn to -t. Apparently, it is the extra syllable of the present tense singular that is under pressure. Moreover, the ending of the preterite is easily replaced by the more conspicuous dental suffix of class I. We then get (hy) sakte instead of regular (hy) sakke (he) dropped.

The pressure in this direction also has a counterpart, i.e. the tendency in conscious language users to create a greater distance to Dutch. We can see this effect with those foreign words that once entered the language under the influence of French, especially the verbs ending in French -er. The corresponding loan in Dutch has an infinitive ending in -eren. Frisian has two, or actually three possibilities. The main choice is between -eare, a class I ending, and -earje, which belongs to class II. Especially in the written language we see a strong preference for -earje. Moreover, this class II suffix has two subvarieties, one broken and one unbroken. As breaking is a typical Frisian sound feature, it is the broken variant that is most popular among the group mentioned. See for more details breaking.

The transition of the verb hoopje to hope was already signalled in 1889 in Van Blom (1889:99). Breuker (1982:24-25) mentions several verbs that are also subject to the transition. Hoekstra (1993) reports on the various stages of transition within the verbal paradigm. De Haan (1990:105-108) represents the view that the change is a Frisian internal one in the first place, although he admits that it can not be separated from the Dutch-Frisian contact situation.

- 1889Beknopte friesche Spraakkunst voor den tegenwoordigen tijdLeeuwardenJ.W. Muller

- 1889In wirdke op 'e krityk fen Dr. Buitenrust Hettema oer de Beknopte Friesche SpraakkunstForjit my net1997-105

- 2012Wangeroogische i-Verben. Betrachtungen zum Verbsystem des ausgestorbenen ostfriesischen Dialekts der Insel WangeroogeUs Wurk61, 3-4125-141

- 2013Die Entwicklung der nordfriesischen schwachen Verben in den nördlichen Mundarten des nordfriesischen Festlandes, ausgehend vom nordergoesharder DialektMasterarbeit, Fach Friesische Philologie der Philosophischen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel

- 2013Die Entwicklung der nordfriesischen schwachen Verben in den nördlichen Mundarten des nordfriesischen Festlandes, ausgehend vom nordergoesharder DialektMasterarbeit, Fach Friesische Philologie der Philosophischen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel

- 2013Die Entwicklung der nordfriesischen schwachen Verben in den nördlichen Mundarten des nordfriesischen Festlandes, ausgehend vom nordergoesharder DialektMasterarbeit, Fach Friesische Philologie der Philosophischen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel

- 2013Die Entwicklung der nordfriesischen schwachen Verben in den nördlichen Mundarten des nordfriesischen Festlandes, ausgehend vom nordergoesharder DialektMasterarbeit, Fach Friesische Philologie der Philosophischen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel

- 2013Die Entwicklung der nordfriesischen schwachen Verben in den nördlichen Mundarten des nordfriesischen Festlandes, ausgehend vom nordergoesharder DialektMasterarbeit, Fach Friesische Philologie der Philosophischen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel

- 2013Die Entwicklung der nordfriesischen schwachen Verben in den nördlichen Mundarten des nordfriesischen Festlandes, ausgehend vom nordergoesharder DialektMasterarbeit, Fach Friesische Philologie der Philosophischen Fakultät der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel

- 2009An Introduction to Old Frisian. History, Grammar, Reader, GlossaryAmsterdam/PhiladelphiaJohn Benjamins Publishing Company

- 1982YnterferinsjesBreuker, Pieter et al (ed.)Bydragen ta de didaktyk fan it Frysk yn it fuortset ûnderwiisFrysk Ynstitút RUG & AFUK23-42

- 1863Beknopte Friesche spraakkunst voor den tegenwoordigen tijdZijlstra, Joure

- 1863Beknopte Friesche spraakkunst voor den tegenwoordigen tijdZijlstra, Joure

- 2006De oergong rd>z en rt>ts yn it SkiermûntseagerskUs Wurk5580-110

- 1824Woordenboek op de gedichten en verdere geschriften van Gijsbert JapicxLeeuwarden, Johannes Proost

- 1902De Vlugge Fries. Handleiding om zonder onderwijzer in korten tijd Friesch te leeren lezen, schrijven en sprekenKampenZalsman

- 1902De Vlugge Fries. Handleiding om zonder onderwijzer in korten tijd Friesch te leeren lezen, schrijven en sprekenKampenZalsman

- 1969Beknopte spraakkunst van het SchiermonnikoogsLjouwert/LeeuwardenFryske Akademy

- 1969Beknopte spraakkunst van het SchiermonnikoogsLjouwert/LeeuwardenFryske Akademy

- 1969Beknopte spraakkunst van het SchiermonnikoogsLjouwert/LeeuwardenFryske Akademy

- 1969Beknopte spraakkunst van het SchiermonnikoogsLjouwert/LeeuwardenFryske Akademy

- 1948Beknopte Friese SpraakkunstGroningenJ.B. Wolters

- 1990Grammatical borrowing and language change: the Dutchification of FrisianJournal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development11101-118

- 1988Miendest dat?Friesch Dagblad09-01Taalsnipels 59

- 1990Hy smokte in sigretFriesch Dagblad13-01Taalsnipels 133

- 1997Pro-drop, clitisering en voegwoordcongruentie in het WestgermaansHoekstra, E. & Smits, C. (eds.)Vervoegde voegwoorden: lezingen gehouden tijdens het Dialectsymposion 1994Amsterdam68-86

- 2001Comparative Aspects of Frisian Morphology and SyntaxMunske, Horst Haider, Århammar, Nils, Hoekstra, J.F., Vries, O., Walker, A.G.H., Wilts, O. & Faltings, V.F. (eds.)Handbuch des FriesischenMax Niemeyer775-786

- 2001Comparative Aspects of Frisian Morphology and SyntaxMunske, Horst Haider, Århammar, Nils, Hoekstra, J.F., Vries, O., Walker, A.G.H., Wilts, O. & Faltings, V.F. (eds.)Handbuch des FriesischenMax Niemeyer775-786

- 2001Standard West FrisianMunske, Horst Haider, Århammar, Nils, Hoekstra, J.F., Vries, O., Walker, A.G.H., Wilts, O. & Faltings, V.F. (eds.)Handbuch des Friesischen / Handbook of Frisian StudiesMax Niemeyer83-98

- 2013Do seachdest der idd aardig wasted út ja. De 2de persoan iental doetiid fan 'e sterke tiidwurden yn it Frysk fan 'e jongereinUs Wurk621-20

- 2013Do seachdest der idd aardig wasted út ja. De 2de persoan iental doetiid fan 'e sterke tiidwurden yn it Frysk fan 'e jongereinUs Wurk621-20

- 1993It feroaringsproses by de je-tiidwurdenTydskrift foar Fryske Taalkunde843-51

- 1919Dongeradielster en Skiermûntseager FryskSwanneblommen1161-167

- 1933Friesche dialectgeographieMartinus Nijhoff

- 1951Hjoeddeiske lûd- en foarmforoaringen 6. Lûdwiksel yn 'e pogge. (II.)De Pompeblêdden: tydskrift foar Fryske stúdzje2234-36

- 2006De je-werkwoorden in de Friese dialecten van het G(oeman)TRPTaal en Tongval58115-134

- 1954De spraakkunst der Terschellinger dialectenAssenVan Gorcum & Comp.

- 1954De spraakkunst der Terschellinger dialectenAssenVan Gorcum & Comp.

- 1954De spraakkunst der Terschellinger dialectenAssenVan Gorcum & Comp.

- 1954De spraakkunst der Terschellinger dialectenAssenVan Gorcum & Comp.

- 1980d(e) Deletion in the past tense of class II weak verbs in Old FrisianLinguistic studies offered to Berthe SiertsemaAmsterdamRodopi277-286

- 1980d(e) Deletion in the past tense of class II weak verbs in Old FrisianLinguistic studies offered to Berthe SiertsemaAmsterdamRodopi277-286

- 1987Woa'deboek fan ut AmelandsFryske Akademy

- 2006Grammatica FriesUtrecht/ LjouwertUitgeverij Het Spectrum BV Prisma Woordenboeken en Taaluitgaven/ Fryske Akademy

- 1904Lytse Fryske spraekleare, it Westerlauwersk om 1900 hinne oangeandeLjouwertR. van der Velde

- 1913Phonology and Grammar of Modern West FrisianLondon, New YorkOxford University Press

- 1913Phonology and Grammar of Modern West FrisianLondon, New YorkOxford University Press

- 1925Nieuwe Friesche SpraakkunstLeeuwardenR. van der Velde

- 1925Nieuwe Friesche SpraakkunstLeeuwardenR. van der Velde

- 1963Op 'e taelhelling. Losse trochsneden fan Frysk taellibben. IBoalsertA.J. Osinga

- 1985Kantekers. Fersprate stikken oer taal en literatuerStifting Freonen Frysk Ynstitút oan de Ryksuniversiteit te Grins (FFYRUG)

- 1980Praat my net fan pratenSikkema, K., Breuker, Ph.H. & Veen, K.F. v.d. (eds.)Coulonnade: Twa-en-tweintich FAriaasjes oanbean oan mr. dr. K. de VriesLjouwert122-130

- 2001Das WanderoogischeMunske, Horst Haider, Århammar, Nils, Hoekstra, J.F., Vries, O., Walker, A.G.H., Wilts, O. & Faltings, V.F. (eds.)Handbuch des FriesischenMax Niemeyer423-429

- 2003Werom yn de tiid foar de hitende foarmFriesch Dagblad23-8-2003?

- 1993In kwestje fan haastjen: oer hoe't yn it Frysk de sekwinsjes -sts en -tj mijd wurdeTydskrift foar Fryske Taalkunde8123-130

- 2002Eilander Wezzenbúek: woordenboek van het SchiermonnikoogsFryske Akademy Ljouwert

- 1992Komprimierung und Differenzierung in der Verbflexion des WestfriesischenPhilologia Frisica 1990, Fryske Akademy167-193

- 1993Schwache Verben ohne Dental-Suffix im Friesischen, Färöischen und im NynorskSchmidt-Radefeldt, J. & Harder, A. (eds.)Sprachwandel und Sprachgeschichte (Tübingen)TübingenGünter Narr Verlag221-237