- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

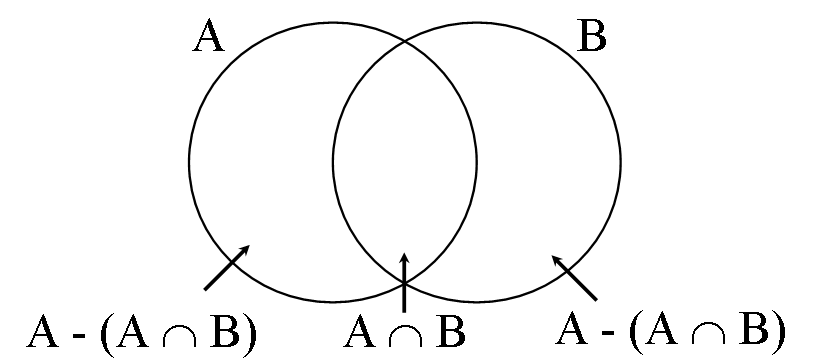

The easiest way of explaining the core meaning of the articles is by using Figure 1 from Section 1.1.2, sub IIA, repeated below, which can be used to represent the subject-predicate relation in a clause. In this figure, A represents the denotation set of the subject NP and B the set denoted by the verb phrase. The intersection A ∩ B denotes the set of entities for which the proposition expressed by the clause is claimed to be true. In an example such as Jan wandelt op straat, for example, it is claimed that the set denoted by A, viz. {Jan}, is properly included in set B, which is constituted by people walking in the street. In other words, it expresses that A - (A ∩ B) = ∅.

The core function of the determiners is to specify the intersection (A ∩ B) and the remainder of set A, that is, A - (A ∩ B). The definite article de/het'the' in (6) expresses that in the domain of discourse (domain D), all entities that satisfy the description of the NP are included in the intersection A ∩ B, that is, that A - (A ∩ B) = ∅. The singular noun phrase de jongen'the boy' in (6a) has therefore approximately the same interpretation as the proper noun Jan in the discussion above; it expresses that the cardinality of A ∩ B is 1 (for which we will use the notation: |A ∩ B| = 1). The only difference between the singular and the plural example in (6) is that the latter expresses that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1.

| a. | De jongen | loopt | op straat. | |

| the boy | walks | in the.street |

| a'. | de/het Nsg: |A ∩ B| = 1 & A - (A ∩ B) = ∅ |

| b. | De jongens | lopen | op straat. | |

| the boys | walk | in the.street |

| b'. | de Npl: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 & A - (A ∩ B) = ∅ |

The semantic contribution of the indefinite articles in (7a&b) is to indicate that A ∩ B is not empty; they do not imply anything about the set A - (A ∩ B), which may or may not be empty. The difference between the singular indefinite article een and the (phonetically empty) plural indefinite article ∅ is that the former expresses that |A ∩ B| = 1, whereas the latter expresses that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1.

| a. | Er | loopt | een jongen | op straat. | |

| there | walks | a boy | in the.street | ||

| 'There is a boy walking in the street.' | |||||

| a'. | een Nsg: |A ∩ B| = 1 & |A - (A ∩ B)| ≥ 0 |

| b. | Er | lopen ∅ | jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | boys | in the.street | ||

| 'There are boys walking in the street.' | |||||

| b'. | ∅ Npl: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 & |A - (A ∩ B)| ≥ 0 |

It is important to note that only parts of the meaning descriptions in the primed examples of (6) and (7) are inherently linked to the determiner: definite articles imply that A - (A ∩ B) = ∅, whereas indefinite articles do not. The claims with respect to the cardinality of the intersection A ∩ B do not come from the articles but from the number (singular versus plural) marking on the nouns: singular marking expresses that |A ∩ B| = 1, whereas plural marking expresses that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1. It is therefore not surprising that the difference between definite and indefinite noun phrases headed by a non-count like wijn 'wine' is that the former refers to a contextually determined amount of wine, whereas the latter simply refers to an indeterminate amount of wine.

The meaning that we attribute to the number marking, which is due to Farkas & De Swart (2008), may come as a surprise. First, the meaning attributed in (7a) to the singular indefinite noun phrase breaks with the tradition in formal semantics that translates the indefinite article by means of the existential operator ∃x, which implies that the article expresses that the intersection A ∩ B contains at least one member, that is, |A ∩ B| ≥ 1. Second, (7b) attributes this meaning instead to the plural marking, which seems to conflict with the fact that plural nouns are normally interpreted as expressing that the intersection A ∩ B contains more than one member, that is, |A ∩ B| > 1. Below, we will therefore motivate why we adopt the proposal by Farkas & De Swart (who actually assume that the plural marking is ambiguous and can express either |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 or |A ∩ B| > 1, but we will ignore this here).

The traditional assumption that indefinite singular noun phrases express that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 predicts that a speaker would use an indefinite singular noun phrase if he has no clue about the cardinality of a certain set. The proposal here, according to which the plural marking on the noun expresses that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1, on the other hand, predicts that the speaker would use an indefinite plural noun phrase in that case. That the latter prediction is correct becomes clear when we consider the questions in (): if a speaker is interested whether the addressee is a parent, that is, whether the addressee has one or more children, the typical way of asking the question would be as given in (8a), not as in (8b).

| a. | Heb | je | kinderen? | |

| have | you | children | ||

| 'Do you have children?' | ||||

| b. | # | Heb | je | een kind? |

| have | you | a child | ||

| 'Do you have a child?' | ||||

Example (8b) is, of course, not ungrammatical but can only be used if the speaker presupposes that the cardinality of the referent set will not be larger that one: so one could ask a question like Heb je al een kind?'Do you already have a child?' if the presupposition is that under normal circumstances the addressee would be childless. For the same reason, examples such as (9a) require that the singular be used, given that this expresses that the speaker is aware of the fact that people normally have just one nose; using the plural would violate Griceʼs (1975) maxim of quantity as this would wrongly suggest that the speaker lacks this knowledge. Similarly, by opting for one of the options in (9b) may make more explicit what the speaker actually desires, a single cigarette or, e.g., a packet of cigarettes.

| a. | Heb | jij | een mooie neus/#mooie neuzen? | |

| have | you | a beautiful nose/beautiful noses | ||

| 'Do you have a beautiful nose/beautiful noses?' | ||||

| b. | Heb | je | een sigaret/sigaretten | voor me? | |

| have | you | a cigarette/cigarettes | for me | ||

| 'Do you have a cigarette/cigarettes for me?' | |||||

Another context that licenses the use of a plural indefinite noun phrase involves clauses containing the modal willen'to want'. Consider the two examples in (10): example (10a) is similar to (8a) in that it inquires whether the addressee is planning to have one or more cats as a pet; example (10a) would be infelicitous in this use and instead suggests that the speaker has a certain cat in mind that is on offer.

| a. | Wil | je | katten? | |

| want | you | cats | ||

| 'Do you want cats?' | ||||

| b. | # | Wil | je | een kat? |

| want | you | a cat | ||

| 'Do you want a cat?' | ||||

A third case in which the speaker may use a plural indefinite noun phrase to express that he has no presupposition about the cardinality is in the case of inferences. When the speaker is visiting some people that he does not know intimately and enters a room littered with toys, he could utter something like (11a) without excluding the possibility that his hosts have only one child. For at least some speakers, using example (11b) is less felicitous in this context as it may suggest that the speaker has reason to believe that the cardinality of the set of children is one.

| a. | Er | wonen | hier | kinderen. | |

| there | live | here | children | ||

| 'There are children living here.' | |||||

| b. | # | Er | woont | hier | een kind. |

| there | lives | here | a child | ||

| 'There is a child living here.' | |||||

That the singular number marking in definite noun phrases like (6a) implies that the intersection has the cardinality 1 seems uncontroversial, which means that Farkas & De Swartʼs proposal makes it possible to assign a single meaning to the singular: |A ∩ B| = 1. That the plural marking in definite phrases like (6b) can express |A ∩ B| ≥ 1 is harder to establish. This is due to the fact discussed in Section 5.1.1.2 below that the definite article generally presupposes that the speaker and the addressee are able to indentify the referents in the referent set of the noun phrase. In the majority of cases the speaker will therefore know whether the cardinality of the referent set is one or more than on. If the former is the case, using a singular definite noun phrase will be more informative than using a plural definite noun phrase; the former will therefore be preferred by Griceʼs maxim of quantity.

Nevertheless, there are certain contexts that show that plural definite noun phrases do not make any implication concerning the cardinality of the referent set. Picture some employee of a company responsible for dealing with custumers’ complaints. When he comes into the office in the morning, he begins by having a look at the newly arrived complaints, at least, if there are any. One morning, there is no post on his desk; he picks up the phone and asks the person who normally sorts and distributes the post the question in (12a), which sort of presupposes that there will be some new complaints but does not imply anything about the number of those complaints. In this respect, (12a) is crucially different from (12b), which implies that the referent set has the cardinality 1.

| a. | Kan | je | me | de nieuwe klachten | brengen? | |

| can | you | me | the new complaints | bring | ||

| 'Can you bring me the new complaints?' | ||||||

| b. | Kan | je | me | de nieuwe klacht | brengen? | |

| can | you | me | the new complaints | bring | ||

| 'Can you bring me the new complaint?' | ||||||

The same thing can be observed in conditionals. Example (13a) is taken from a text on family law concerning divorce. Using the singular noun, as in (13b), would be distinctly odd in this context since this would imply that in all cases of a divorce there is only a single child involved; such implications are completely absent in examples such as (13a). The examples in (12) and (13) again support the proposal by Farkas & De Swart, which assigns a single meaning to the plural: |A ∩ B| ≥ 1.

| a. | Als | de kinderen | aan één van de ouders | zijn toegewezen, | dan ... | |

| if | the children | to one of the parents | are prt.-awarded | then | ||

| 'If one of the parents is awarded the custody of the children ...' | ||||||

| b. | # | Als | het kind | aan één van de ouders | is toegewezen, | dan ... |

| if | the child | to one of the parents | is prt.-awarded | then |

The semantic function of the negative article geen'no' is to indicate that the intersection of A and B is empty: A ∩ B = ∅. No claims are made about set A or set B: it may or may not be the case that domain D contains a set of boys and/or that there is a set of people who are walking in the street.

| a. | Er | loopt | geen jongen | op straat. | |

| there | walks | no boy | in the.street |

| a'. | geen Nsg: A ∩ B = ∅ & |A - (A ∩ B)| ≥ 0 |

| b. | Er | lopen | geen jongens | op straat. | |

| there | walk | no boys | in the.street |

| b'. | geen Npl: A ∩ B = ∅ & |A - (A ∩ B)| ≥ 0 |

The distinction between singular and plural is again not related to the meaning of the article: examples like (14a&b) can be used to deny a presupposition that, respectively, |A ∩ B| = 1 or |A ∩ B| ≥ 1. If no such presupposition is present, the plural is used. Consider the situation in which Jan is in hospital with a fractured leg. He is bored stiff and therefore his friend Peter always brings him something to read when he is visiting: the number of books varies depending on their size. One day Peter enters the hospital ward empty-handed. In this case Jan will probably ask the question in (15a) and not the one in (15b), given that the latter presupposes that Peter normally brings just one book.

| a. | Heb | je | geen boeken | voor me | meegenomen? | |

| did | you | no books | for me | prt-.taken | ||

| 'Didnʼt you bring me any books?' | ||||||

| b. | # | Heb | je | geen boek | voor me | meegenomen? |

| did | you | no book | for me | prt-.taken |

The meaning contributions of the three articles can be summarized by means of the table in example (16). There are no implications concerning the cardinality of the intersection giventhat it is the role of the number marking of the noun to specify this: the singular marking expresses that |A ∩ B| = 1 and the plural marking that |A ∩ B| ≥ 1.

| A ∩ B | A - (A ∩ B) | |

| definite article de/het | non-empty | empty |

| indefinite article een/∅ | non-empty | indeterminate |

| negative article geen | empty | indeterminate |

In the following sections we will see, however, that more can be said about the precise characterization of the meaning of the articles, and it will also become clear that some uses of the articles do not fall under the general characterization of the meaning of the articles given in this section.

- 2008Formal and semantic markedness of number

- 1975Logic and conversationCole, P. & Morgan, J. (eds.)Speech acts: Syntax and Semantics 3New YorkAcademic Press41-58