- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

A complement clause is a subordinate clause that functions, formally, as an argument of a main-clause verb, or else of an adjective or noun. The complement clause completes the meaning of the main-clause verb, adjective or noun. In the most typical case, the complement clause is embedded in a higher clause as the direct object of a main-clause verb, as in (1), in which the lexical verb vermoed suspect controls the complement clause. Complement clauses can also be controlled by a copular verb + adjective, as in (2). Less frequently, head nouns may take complement clauses, as in (3).

| Navorsers vermoed dat hierdie variasies onderliggend is aan mense se vatbaarheid vir siektes. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| researchers suspect that.COMP these variations underlying be.PRS to people PTCL.GEN susceptibility for illnesses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Researchers suspect that these variations are underlying to people's susceptibility to illness. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Verb complement] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Navorsers is seker dat hierdie variasies onderliggend is aan mense se vatbaarheid vir siektes. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| researchers be.PRS sure that.COMP these variations underlying be.PRS to people PTCL.GEN susceptibility for illnesses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Researchers are sure that these variations are underlying to people's susceptibility to illness. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Adjective complement] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Die aanname dat hierdie variasies onderliggend is aan mense se vatbaarheid vir siektes is aanvegbaar. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the assumption that.COMP these variations underlying be.PRS to people PTCL.GEN susceptibility for illnesses be.PRS contentious | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The assumption that these variations are underlying to people's susceptibility to illness is contentious. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Noun complement] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

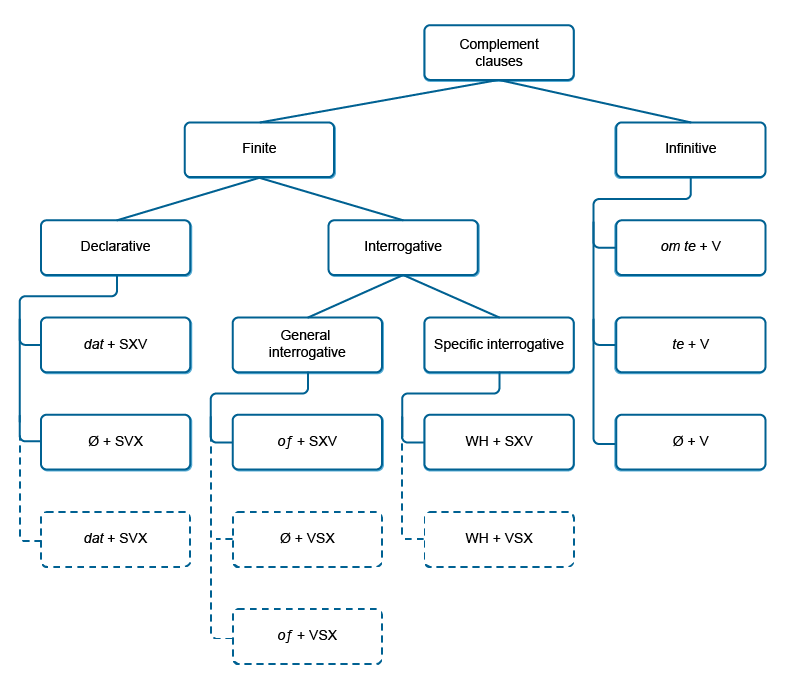

Afrikaans has three formally distinguishable complement clause types: finite declarative complement clauses, finite interrogative complement clauses and infinitive complement clauses. Each of these complement clause types has a number of variants that hinge on the presence or absence of a complementiser and accompanying word-order alternations. Some of these variants are typical of spoken language, or are regarded as non-standard. These variants are summarised in Figure 1, with non-standard or spoken-language variants indicated with dashed rather than solid lines.

Finite declarative clauses in Afrikaans may take the form of a complement clause introduced with the complementiserdat that, followed by verb-final word order marking the subordinate status of the complement clause, as in (4). In spoken language, a variant with dat, but with main-clause word order also occurs, exemplified in (5). This word order is not regarded as acceptable by all speakers of Afrikaans, but occurs quite widely in spoken language (Feinauer 1990; Bibrauer 2002). The complementiser is also commonly omitted, in which case it is followed by a complement clause with main-clause (verb-second) word order, as in (6).

| Ek wens dat ek my baadjie saamgebring het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wish that.COMP I my jacket brought.along.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wish that I had brought my jacket along. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [dat+SXV] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ...so ja dis eintlik hartseer dat jou taal is nie meer wat dit was nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| so yes it's actually sad that.COMP your language be.PRS not anymore what it be.PST PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ...so, yes, it's actually sad that your language isn't what it was anymore. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [dat+SVX] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 'n Bron by die kafee sê aan Son hul toilette is vir die afgelope twee maande buite werking. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a source at the cafe say to Son their toilets be.PRS for the past two months out.of order | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A source at the cafe told Son their toilets have been out of order for the past two months. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [ø+SVX] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Finite interrogative clauses may be introduced by the complementiser of if/whether or a wh-word (wanneer when; wat what; waar where; hoekom why; watter what/which). Interrogative complement clauses introduced by of are general interrogatives (indirect yes/no questions). They typically have dependent (verb-final) word order, as in (7). However, in spoken language a variant with main-clause interrogative word order (verb in initial position) also occurs, as in (8), but the word order is not grammatically acceptable to all speakers of Afrikaans. If of is omitted, main-clause interrogative word-order is used, as in (9).

| Reisagentskappe en lugdienste kon gister nie sê of daar 'n toename in besprekings vir vlugte na Johannesburg is nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| travel agencies and airlines could yesterday not say IF.COMP there a increase in bookings for flights to Johannesburg be.PRS PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Travel agencies and airlines could not say yesterday if there was an increase in bookings for flights to Johannesburg. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [of+SXV] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| O ja Pa, ek wil weet of kan ek jou staalborsel leen. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| o yes Dad I want.to.AUX.MOD know.INF if.COMP can.AUX.MOD I your steel.brush borrow.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| O yes, Dad, I'd like to know if I can borrow your steel brush. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [of+VSX] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek gaan jou weer vra het jy hom onder deur die selle ingebring. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I go you again ask have you him under through the cells in.bring.PST | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I am going to ask you again did you bring him in through the cells below. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [ø+VSX] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Specific interrogatives (indirect wh-questions) have the wh-word in the initial position of the complement clause and in dependent-clause word order with the verb in final position, as shown by (10). Here, too, main-clause word order may occur in the complement clause, as in (11).

| Hy wou nie sê hoeveel geld in die saak ingeploeg is nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| he would not say how.much money in the case in.plough.PST be.AUX.PRS.PASS PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| He would not say how much money was ploughed into the case. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [WH+SXV] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hulle vra vir jou wanneer gaan jy see toe. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| they ask for you when go you sea to | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| They ask you when you are going to the sea. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [WH+VSX] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Afrikaans uses three different types of infinitive clauses. The full infinitive form (traditionally known as the long infinitive in the tradition of Afrikaans scholarship) makes use of the complementiser om in order and the particle te to, and is the most typical form for an object clause, as shown by (12). The bare infinitive (traditionally called the short infinitive in Afrikaans scholarship) only uses the infinitive form of the main verb, as in (13), where the governing verb probeer try and the complement clause that is the focus of the analysis are indicated in the syntactic analysis. A historical remnant from its Early Modern Dutch parent is the infinitive clause with the particle te, as shown by (14). It has restricted distribution in contemporary Afrikaans (Deumert 2004:204-207).

| Hierdie terugkoopaksies help om die verwatering van kapitaal te keer. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| these back.buy.actions help for.COMP the dilution of capital PTCL.INF stop | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| These buy-back actions help to stop the dilution of capital. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Full infinitive] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Die ouers probeer verstaan hoe kleuters konflik hanteer. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Die ouers [(VP) verstaan] [(CC) hoe kleuters konflik hanteer] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the parents try.LINK understand.INF how toddlers conflict handle.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The parents try to understand how toddlers handle conflict. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Bare infinitive] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek glo nie ek sal jou weer te siene kry voor daardie tyd nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I believe not I shall you again to see get before that time PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I believe I won't get to see you before then. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [te infinitive] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Related to various complement clause types, especially the finite complement clauses, Afrikaans has a number of options for reporting speech and thought. Constructions used for reporting speech and thought are direct speech and indirect speech, the latter usually realised by complement clauses.

Speech and thought can be reported directly in Afrikaans, most typically with the reporting clause following the reported clause, as shown by (15), or by means of an indirect report, where a main clause contains the reporting verb and a complement clause encodes the reported speech.

| "Wel, daar is Ewigdurende Roem," sê Adriaan terwyl hy 'n paar geklopte eiers by die mengsel in die pan roer. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| well there be.PRS everlasting glory say Adriaan while he a few beaten eggs to the mix in the pan stir | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| "Well, there is Everlasting Glory," Adriaan says while he stirs a few beaten eggs into the mix in the pan. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Direct Speech] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In indirect speech, the reporting clause functions like a syntactic main clause, while the report is conveyed in the complement clause. The complement clause is characterised by a shift in the deictic centre, which is reoriented to the main clause. Both declarative and interrogative complement clauses can be used to report speech indirectly, as shown by (16) and (17) respectively.

| Tydens die gesprek het hy gesê dat hy reeds met die koerant gepraat het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| during the conversation have.AUX he say.PST that.COMP he already with the newspaper speak.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| During the conversation he said that he had already spoken to the newspaper. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Indirect Speech, declarative complement clause] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek vra hom toe of hy vanoggend 'n ekstra bordjie simpelgeit geëet het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I ask.PRS him then if.COMP he this.morning an extra plate stupidity eat.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I then asked him if he ate an extra plate of stupidity this morning | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Indirect Speech, interrogative complement clause] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The three major complement clause types, with their variants, as well as direct and indirect speech, are compared along three parameters throughout this grammar. Each type of complement clause is discussed in terms of three parameters:

- Construction forms: Which syntactic forms (categories and word order) characterise the constructions?

- Syntactic distribution: In which syntactic positions are the constructions used?

- Semantic and lexical associations: With what restricted class of matrix verb predicates is a particular construction typically used?

In addition, during the course of the discussion of these three parameters, the exposition will pay attention to two further types of association of the complement constructions:

- Specific constructions: Which more specific variants of the more general construction emerge and are used in more restricted contexts?

- Functions: Which functions do the constructions perform in discourse?

This section provides an overview of how the parameters operate, and presents and compares the most typical and frequent constructions in Afrikaans for the purpose of illustration. More in-depth treatment is provided in the presentation of the individual constructions.

The first parameter is construction forms. In the various sections presenting the complement clauses in detail, a basic description of the syntactic and lexical categories involved in the construction is offered, as well as the word-order features characteristic of the specific construction.

There are two widespread word orders accepted as standard for finite declarative clauses: verb-final after the complementiserdat and verb-second if no complementiser is used. Example (4), with verb-final word order, can be analysed as follows:

| Ek wens dat ek my baadjie saamgebring het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wens [(CC) [(COMP) dat] [[(SUB) ek] [(OBJ) my baadjie] [(VF) saamgebring het]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wish.PRS that.COMP I my jacket bring.along.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wish that I had brought my jacket along. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If this sentence is used without the complementiser, the syntactic structure changes to verb-second order, shown in example (19):

| Ek wens ek het my baadjie saamgebring. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wens [(CC) [(SUB) ek] [(V2) het] [(OBJ) my baadjie] [(VF) saamgebring]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wish I have.AUX my jacket bring.along.PST | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wish I had brought my jacket along. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The third, non-normative variant of finite declarative complement clauses uses the complementiser dat, but with verb-second word order, as the syntactic analysis in (20) shows.

| Ek wens dat ek het my baadjie saamgebring. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wens [(CC) [(COMP) dat] [(SUB) ek] [(V2) het] [(OBJ) my baadjie] [(VF) saamgebring]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wish.PRS that.COMP I have.AUX my jacket bring.along.PST | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wish that I had brought my jacket along. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With finite specific-interrogative complement clauses (yes/no questions), the verb-final word order is also selected after the complementiser of, as shown in example (21).

| Ek wonder of ek my baadjie saamgebring het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(Comp) of] [[(SUB) ek] [(OBJ) my baadjie] [(VF) saamgebring het]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS if.COMP I my jacket bring.along.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if I have brought my jacket along. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, if no complementiser is used, then the complement clause takes a verb-first order like direct main-clause questions, with the inversion of the subject and verb, as in (22), although Feinauer (Feinauer 1989) points out that this variant is quite rare in her data.

| Ek wonder het ek my baadjie saamgebring. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(V1) het] [(SUB) ek] [(OBJ) my baadjie] [(VF) saamgebring]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder have I my jacket brought.along | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if I have brought my jacket along. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The non-normative variant uses the complementiser of, combined with verb-first main order like direct main-clause questions. The form of this construction is exemplified in (23).

| Ek wonder of het ek my baadjie saamgebring. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(V1) het] [(SUB) ek] [(OBJ) my baadjie] [(VF) saamgebring]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS if.COMP have.AUX I my jacket bring.along.PST | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if I have brought my jacket along. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Indirect wh-interrogatives show more variability between the normatively preferred verb-final word order, and the verb-second order that characterises main-clause wh-interrogatives. Biberauer (2002) reports that the verb-final order is by far the dominant form in written Afrikaans, as exemplified by (24), but in spoken Afrikaans the majority (70%) of indirect interrogatives have verb-second order, as exemplified by (25).

| Ons moet uitvind hoe dit presies gebeur het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ons moet uitvind [(CC) [(WH) hoe] [(SUB) dit] [(ADV) presies] [(VF) gebeur het]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| we must.AUX.MOD out.find.INF how it exactly happen.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| We must find out how exactly it happened. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek wonder wat het hy vandag weer aangevang? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(WH) wat] [(V2) het] [(SUB) hy] [(ADV) vandag weer] [(VF) aangevang]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS what have.AUX he today do.PST | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder what he has done today. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (Biberauer 2002:37) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Infinitive complement clauses display limited word order variability. The full or long infinitive is always introduced by a complementiser, usually om, although variants with deur by and ten einde in order also occur, and the verb is always in the final position, immediately preceded by the infinitive particlete to. Other elements, such as direct objects or adjuncts are between the complementiser and the verb, as illustrated by (12) above, which is analysed as in (26):

| Hierdie terugkoopaksies help om die verwatering van kapitaal te keer. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) hierdie terugkoopaksies help [(CC) [(COMP) om] [(OBJ) die verwatering van kapitaal] [(VF) te keer]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| these back.buy.actions help.PRS for.COMP the dilution of capital PTCL.INF stop.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| These buy-back actions help to stop the dilution of capital. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Bare or short infinitive clauses have extremely limited syntactic options. According to Ponelis (1979:431-432), apart from the infinitive verb itself, only a generic noun that functions as verb complement or a short adjunct is allowed, immediately preceding the verb as shown by example (27), where the bare infinitive functions as subject of the main clause:

| Ontbyt eet is gesond. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) [(CC) [(OBJ) ontbyt] [(VF) eet]] [(V2) is][(PRED) gesond]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| breakfast eat.INF be.PRS healthy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eating breakfast is healthy. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ponelis (1979: 432) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The second parameter is syntactic distribution, which refers to the roles of the constructions in complex sentences. Verb complement clauses of all three main structural types can occur in both post-predicate (object) and pre-predicate (subject) position (though there are some restrictions on syntactic distribution for subtypes of the various complement clauses).

The object position is most typical, and has already been illustrated in the preceding discussion. Some examples are repeated here for ease of reference. Example (28) shows a finite declarative clause in object position, while (29) and (30) demonstrate the two types of interrogative complement clauses in object position. Example (31) illustrates an infinitive complement clause in object position.

| Ek wens dat ek my baadjie saamgebring het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [ek wens [(OBJ) dat ek my baadjie saamgebring het]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wish.PRS that.COMP I my jacket bring.along.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wish that I have brought my jacket along. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reisagentskappe en lugdienste kon gister nie sê of daar 'n toename in besprekings vir vlugte na Johannesburg is nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [reisagentskappe en lugdienste kon gister nie sê [(OBJ) of daar 'n toename in besprekings vir vlugte na Johannesburg is nie]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| travel agencies and airlines can.AUX.MOD.PRT yesterday not say.INF if.COMP there a increase in bookings for flights to Johannesburg be.PRS PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Travel agencies and airlines could not say yesterday if there was an increase in bookings for flights to Johannesburg. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hy wou nie sê hoeveel geld in die saak ingeploeg is nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [hy wou nie sê [(OBJ) hoeveel geld in die saak ingeploeg is nie]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| he will.AUX.MOD.PRT not say how.much money in the case in.plough.PST be.AUX.PRS.PASS PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| He would not say how much money was ploughed into the case. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek gaan tog van jou verwag om die inhoud te memoriseer. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [ek gaan tog van jou verwag [(OBJ) om die inhoud te memoriseer]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I go.LINK indeed of you expect.INF for.COMP the content PTCL.INF memorise | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I am going to expect of you to memorise the content. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Complement clauses of all three main types may be used in subject position, as shown in the following examples. Example (32) illustrates the use of a finite declarative complement clause as subject. The two finite interrogative clause types, wh-interrogative and general interrogative, in subject position are illustrated by (33) and (34). The use of the full infinitive clause as subject is shown by (35).

| Dat voëls migrasie bo hibernasie gebruik maak logiese sin. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [[(SUB) dat voëls migrasie bo hibernasie gebruik] maak logiese sin] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| that.COMP birds migration above hibernation use.PRS make.PRS logical sense | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| That birds use migration rather than hibernation makes logical sense. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Waarom ek aan antie skryf, is om te hoor wat ek nog kan doen om dié man my true love te maak. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [[(SUB) waarom ek aan antie skryf] is om te hoor wat ek nog kan doen om dié man my true love te maak] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| why I to aunty write.PRS is for.COMP PTCL.INF hear.INF what I else can.AUX.MOD do.INF for.COMP this man my true love PTCL.INF make.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Why I write to you, Aunty, is to hear what else I can do to make this man my true love. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Of die geld ontvang of betaal is vir die huidige boekjaar of vir die vorige of die volgende boekjaar maak nie saak nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [[(SUB) of die geld ontvang of betaal is vir die huidige boekjaar of vir die vorige of die volgende boekjaar] maak nie saak nie] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| if.COMP the money received or paid be.PRS for the current book.year or for the previous or the following book.year make.PRS not case PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Whether the money is received or paid for the current financial year, or the previous or following year does not matter. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Om genoteer te wees, verleen onmiddelik aansien aan jou maatskappy. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [[(SUB) om genoteer te wees] verleen onmiddelik aansien aan jou maatskappy] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| for.COMP listed PTCL.INF be.INF lend.PRS immediate esteem to your company | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| To be listed, immediately lends esteem to your company. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While Afrikaans allows the use of complement clauses in subject position, it is more likely to use the extraposition construction with the dummy subjectDit It in the initial position of the main clause (Bosch 1998:121), and the complement clause in its entirety moved to the position after the main clause, as illustrated in (36)-(38) where the subject clause is moved to the final position. The examples illustrate the extraposition of a finite declarative (36), finite general interrogative (37) and infinitive (38) complement clause respectively.

| Dit blyk uit navorsing dat umbilikale bloed 'n ryk bron van stamselle is. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [[dit] blyk uit navorsing [(SUB) dat umbilikale bloed 'n ryk bron van stamselle is]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it appear.PRS from research that.COMP umbilical blood a rich source of stem.cells be.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It appears from research that umbilical blood is a rich source of stem cells. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit maak nie saak of jy romans of draaiboeke of fokken fairy tales skryf nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [[dit] maak nie saak [(SUB) of jy romans of draaiboeke of fokken fairy tales skryf] nie] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it make.PRS no matter if.COMP you novels or film.scripts or fucking fairy tales write.PRS PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It doesn't matter if you write novels, film scripts or fucking fairy tales. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit is 'n fout om hierdie politikus bloot as 'n openbare nar te sien. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [[dit] is 'n fout [(SUB) om hierdie politikus bloot as 'n openbare nar te sien]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it be.PRS a mistake for.COMP this politician simply as a public clown PTCL.INF see.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It is a mistake to view this politician simply as a public clown. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adjusted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lastly, complement clauses may fulfil the role of complementive (or subject predicative to a copular verb), as in (39). In these cases, the complement clause provides additional information about the subject of the main clause.

| Die doel van die trust is om aan die trustbegunstigdes die inkomste van die trust beskikbaar te stel vir hulle opvoeding... | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [die doel van die trust is [(PRED)om aan die trustbegunstigdes die inkomste van die trust beskikbaar te stel vir hulle opvoeding]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the purpose of the trust be.PRS for.COMP to the trust.beneficiaries the income of the trust available PTCL set.INF for their education | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The purpose of the trust is to make the income of the trust available to the trust beneficiaries for their education. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Complement clauses can also function as complements to other parts of speech, particularly as noun or adjective complements.

Complement clauses are not used freely, but are constrained by the semantics of the main-clause verb. Verbs from specific semantic classes typically take specific complement constructions, but are less frequently combined with others and may even be incompatible with some complement clause types. Verbs that denote communication or mental processes typically take finite complement clauses, and are therefore often employed in the function of reporting speech indirectly. There is a further constraint, in that a number of assertive verbs usually take finite declarative clauses, as illustrated by (40), while verbs that indicate uncertainty are more likely to take finite interrogative clauses, as illustrated by (41).

| Behou Jake White, hy het al deur en deur bewys dat hy die beste afrigter vir Suid-Afrika is. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| keep.IMP Jake White he have.AUX already through and through prove.PST that.COMP he the best coach for South-Afica be.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Keep Jake White, he has already proven thoroughly that he is the best coach for South Africa. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ons moet onsself vra of ons die regte resultate kry. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| we must.AUX.MOD ourselves ask.INF if.COMP we the right results get.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| We must ask ourselves if we get the right results. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Verbs of causation often take full infinitive clauses, as shown by the verb forseer force in example (42).

| Metaalkontakte aan die bo- en onderpunte van die sel skep 'n elektriese veld wat die vrye elektrone forseer om in 'n bepaalde rigting te beweeg. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| metal.contacts on the top- and bottom.ends of the cell create.PRS an electrical field which the free electrons force.PRS for.COMP in a determined direction PTCL.INF move.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Metal contacts at the top and bottom ends of the cell create an electrical field which forces the free electrons to move in a specific direction. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Below the most general or schematic level, a number of specific grammatical patterns emerge, where specific variants of constructions are associated closely with particular main-clause verbs. Such constructions are less schematic, or productive, than the more general complement constructions (of which they form a sub-construction). They can be regarded as characteristic usage patterns in Afrikaans that have a high degree of salience in the grammar and fulfil very specific functions. In the specific sections where the various complement clause types are discussed in detail, more comprehensive quantification and an analysis of the functions of these specific constructions are offered. By way of illustration, a small sample of such constructions is presented in (43) to (47), which are all based on the analysis of data from the Taalkommissie Corpus (TK). The point is not that alternative formulations and combinations are not available to users of Afrikaans, but rather that speakers of Afrikaans use these options with considerably higher frequency than others, and they are likely to be prefabricated or idiomatic expressions that form part of the grammatical knowledge of speakers.

A number of fixed main-clause expressions can be identified among finite declarative complement clauses. Ek moet bieg (dat) I must confess that is one such salient fixed expression, as illustrated in (43). It has a strong preference for the modal moet must, and demonstrates limited schematicity. For instance, the verb bieg confess infrequently combines with subjects other than the first-person singular pronoun.

| Die gevolg is dat ek meer preke as die meeste mense al moes aanhoor. Ek moet egter bieg dat daar in al die jare omtrent net vyf preke is wat ek kan onthou. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... I must.AUX.MOD however confess.INF that.COMP there in all the years about only five sermons be.PRS which I can.AUX.MOD remember.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The result is that I have had to listen to more sermons than most people. I must however confess that in all those years there were about only five sermons that I can remember. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The interrogative main clause WH dink jy (dat) WH do you think (that), illustrated in (44) is another specific construction that occurs very frequently, and serves a number of specialised functions. This corresponds in many ways to the Dutch construction WH denk u datWH do you think that, examined by Verhagen (2005).

| Hoekom dink jy het die Galileo-geval die paradigmatiese geval geword vir diegene wat die konflik model aanhang? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| why think.PRS you have.AUX the Galileo-case the paradigm case become.PST for those who the conflict model support.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Why do you think the Galileo-case became the paradigmatic case for those supporting the conflict model? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The causative verb help help frequently takes a full infinitive complement clause. In an analysis of the Taalkommissie Corpus (TK), it emerges that a number of subconstructions can be identified, including the expression SUB kan nie help om te wonder + finite interrogative complement clause SUB can't help but wonder + finite interrogative complement clause, where the schematic subject is usually restricted to one of three: the generic expression 'n mens one, or the first or second person singular pronouns, as illustrated by (45) and (46).

| 'n Mens kan nie help om te wonder hoekom so 'n stuk grond met soveel potensiaal só moet verwaarloos nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... a human can.AUX.MOD not help.INF for.COMP PTCL.INF wonder why such a piece land with so.much potential so must.AUX.MOD neglect.INF PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| One cannot help but wonder why such a piece of land with so much potential must be so neglected. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| …maar ek kan nie help om te wonder of sy besef hoe goed sy werklik is nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... but I can.AUX.MOD not help.INF for.COMP PTCL.INF wonder.INF if.COMP she realise.PRS how good she really be.PRS PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... but I cannot help wondering if she realises how good she really is. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, as illustrated by (47), when the causative verb help is itself part of an infinitive verb phrase, it often does not take a full infinitive complement clause, but the bare infinitive alternative, as illustrated by the verb verseker ensure in this case:

| Immuunonderdrukkers is toegedien om te help verseker dat haar liggaam nie die nuwe weefsel verwerp nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... Immune.suppressors be.AUX.PASS.PST administer.PASS for.COMP PTCL.INF help.LINK ensure.INF that her body not the new tissue reject.PRS PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Immune suppressors were administered to help ensure that her body does not reject the new tissue | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

During the presentation of the grammatical analysis, attention is given to the function of each form of complement clause. To give an overall sense of what is meant by function, two illustrations are offered here.

Finite, declarative complement clauses serve two related functions, which can be distinguished in terms of which part of a particular construal of reality (encoded by the main clause and subordinate clause respectively) is presented as the central claim in discourse. The two functions are the propositional and interpersonal functions. The propositional function is exemplified by (48).

| Dit is van wesenlike belang dat u moet begryp dat hierdie remedie 'n kontrakaksie is. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit is van wesenlike belang [dat u moet begryp [(CC) dat hierdie remedie 'n kontrakaksie is]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it be.PRS of essential importance that.COMP you must.AUX.MOD understand.INF that.COMP this remedy a contract.action be.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It is of utmost importance that you must understand that this remedy is a contractual action. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The sentence starts with a dummy subjectdit it which is expanded by an extraposed subject clausedat u moet begryp dat hierdie remedie 'n kontrakaksie is that you must understand that this remedy is a contractual action. The embedded subject clause itself consists of a main clause and complement clause, and it is these two that illustrate the propositional use of the main clause, u moet begryp you must understand. This clause makes a statement about the world, which is reinforced by the copula predicate of the independent main clause (van wesenlike belang of utmost importance). The complement clause within the embedded subject clause dat hierdie remedie 'n kontrakaksie is that this remedy is a contractual action offers a subpart of the content of that statement by way of elaboration. The main clause of the embedded subject clause u moet begryp you must understand is central to the unfolding of the discourse, and therefore performs a propositional function, rather than being backgrounded to the complement clause.

By contrast, in example (49), the complement clause ek was glad nie senuweeagtig nie I wasn't nervous at all makes the central statement, while the main clause en ek moet sê and I must say serves to ground that statement in the interpersonal interaction between the two communicative partners. The discourse centrality of the complement clause is clear from the content of the preceding sentence Hy het my gevra om 'n bal te slaan He asked me to hit a ball, as well as the following adverbial clause al moes ek dit voor die wêreld se beste speler doen even though I had to do it before the world's best player, which both deal with the speaker playing a tennis ball and how he was not nervous despite being watched by the world's best tennis player. There is no further continuation that relates to the speaker's saying, which in this case clearly does not denote an instance of reported speech, but simply an expression of stance.

| Hy het my gevra om 'n bal te slaan. En ek moet sê ek was glad nie senuweeagtig nie, al moes ek dit voor die wêreld se beste speler doen. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... [En ek moet sê [(CC) ek was glad nie senuweeagtig nie] [(AdvC) al moes ek dit voor die wêreld se beste speler doen.]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| he have.AUX me ask.PST for.COMP a ball PTCL.INF hit.INF and I must.AUX.MOD say.INF I be.PST totally not nervous PTCL.NEG although must.AUX.MOD.PRT I it before the world PTCL.GEN best player do.IND | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| He asked me to hit a ball. And I must say I was not nervous at all, even though I had to do it in front of the world's best player. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The functional contrast between propositional and interpersonal uses is often accompanied by the formal contrast between complement clauses with and without the complementiser. Thus, in (48) the presence of the subordinator dat is a formal signal of the conceptually and formally subordinate status of the complement clause relative to the main clause. However, in (49), there is no overt subordinator, and the complement clause uses main-clause word order, as a signal of its more central contribution to the information offering in context.

A second illustration of the functional explanation is from the contrast between direct and indirect speech. In direct speech, a closer (or even verbatim) rendition of the original wording of a speaker is presented, which usually contributes to a more dramatic effect, but also shifts the responsibility for the veracity or felicity of the statement to the original source, rather than the person reporting. This is exemplified by (50), where the direct quotation is attributed to the original speaker, and is presented as his subjective assessment of his own preference, which the reporter does not necessarily share with him, nor does the reporter claim to be the source of this information.

| "Ag wat, ek is nie 'n man vir verse nie," het hy eenkeer gesê. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| oh well I be.PRS not a man for poems PTCL.NEG have.AUX he one.time say.PST | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| "Oh well, I'm not a man for poetry," he once said. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the case of indirect speech, a more interpreted and potentially summarised version of the original wording is offered, and there is a stronger sense that it is embedded in the discourse of the reporting speaker/writer, who assumes at least shared responsibility for the veracity of the statement. This is exemplified in (51), where the writer is more clearly aligned with the sentiment expressed by the magistrate, which is not a subjective opinion of a single individual, but a widely shared view.

| Landdros Louw sê dit is nie in die belang van geregtigheid om borgtog toe te staan nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| magistrate Louw say.PRS it be.PRS not in the interest of justice for.COMP bail PTCL.INF grant.INF PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magistrate Louw says it is not in the interest of justice to grant bail. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics34

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics34

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: is this a unitary phenomenon?Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics34

- 1998Die onderskikker 'dat': 'n korpus-gebaseerde bespreking (Deel 1).South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde16120-126,

- 2004Language standardization and language change: the dynamics of Cape Dutch.ReeksJ. Benjamins

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinne.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde730-37,

- 1990Skoon afhanklike sinne in Afrikaanse spreektaal.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde8116-120,

- 1979Afrikaanse sintaksis.Van Schaik

- 2005Constructions of intersubjectivity: discourse, syntax, and cognitionOxford/New YorkOxford University Press