- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

The following table gives examples for each single codaconsonant following each of the native Dutch vowels (examples taken from Theissen et al. 1988 and Cohen 1972). A few interesting observations can be made right away:

- The glottalfricative /h/ does not occur in coda position.

- Voiceless fricatives can follow B-class vowels but not A-class vowels.

- Voiced fricatives can follow A-class vowels and diphthongs but not B-class vowels.

- The glides /j, ʋ/ can only follow certain A-class vowels.

- The velarnasal /ŋ/ exclusively follows B-class vowels.

| coda | /ɪ/ | /ʏ/ | /ɛ/ | /ɑ/ | /ɔ/ | /i/ | /y/ | /e/ | /ø/ | /a/ | /o/ | /u/ | /ə/ | /ɛi/ | /œy/ | /ɑu/ |

| /p/ | kip | pup | klep | pap | mop | diep | - | zeep | heup | slaap | knoop | soep | hennep | pijp | kuip | - |

| /t/ | wit | hut | wet | mat | mot | parkiet | minuut | heet | schoet | straat | boot | zoet | lemmet | mijt | spruit | hout |

| /k/ | ik | druk | hek | pak | rok | kubiek | kaduuk | streek | spreuk | haak | spook | boek | -(e)lijk | wijk | pruik | pauk |

| /b/ | rib | schub | neb | krab | lob | Caraïeb | kuub | - | - | Zwaab | aeroob | - | - | - | Huib | - |

| /d/ | jid | mud | bed | pad | verbod | lied | - | kleed | - | daad | rood | hoed | - | meid | huid | koud |

| /f/ | gif | duf | ophef | maf | stof | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | gannef | - | - | - |

| /s/ | vis | bus | bes | kas | bos | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | hannes | krijs | kruis | kous |

| /x/ | wig | mug | beleg | vlag | nog | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | jarig | - | gejuich | - |

| /v/ | - | - | - | - | - | dief | - | neef | gleuf | schaaf | kloof | boef | - | schijf | duif | - |

| /z/ | - | - | - | - | - | kies | excuus | vlees | neus | baas | roos | poes | - | reis | muis | saus |

| /ɣ/ | - | - | - | - | - | vlieg | spuug | deeg | deug | laag | oog | ploeg | - | vijg | getuig | - |

| /h/ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| /m/ | slim | gum | klem | dam | stom | riem | kostuum | systeem | kleum | raam | boom | bloem | bliksem | rijm | pluim | - |

| /n/ | kin | dun | ten | kan | bon | nadien | immuun | been | steun | baan | toon | schoen | (ik) open | termijn | duin | clown |

| /ŋ/ | ding | bungalow | eng | zang | tong | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| /l/ | pil | lul | cel | bal | wol | hiel | moduul | meel | peul | schaal | kool | doel | lepel | pijl | ruil | Paul |

| /r/ | kefir | augur | ster | bar | snor | bier | muur | weer | deur | schaar | school | boer | otter | - | - | - |

| /ʋ/ | - | - | - | - | - | nieuw | uw | eeuw | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| /j/ | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | aai | ooi | roei | - | - | - | - |

Dutch presents some striking co-occurrence restrictions between vowels and voiced and voiceless fricatives. Whereas A-class vowels and diphthongs can only be followed by voiced fricatives, B-class vowels can only be followed by voiceless fricatives. This is illustrated by the following examples:

There are a few exceptions to this observation. In the two loanwords puzzel /pʏzəl/ puzzle and mazzel /mɑzəl/ luck a B-class vowel is followed by a voiced fricative. However, an alternative pronunciation of the first item as [ˈpy.zəl] indicates a speaker preference for a sequence of A-class vowel plus voiced fricative.

Secondly, sequences of A-class vowels and voiceless fricatives seem to occur due to the fact that the pronunciation of the voicing contrast between the two dorsal fricatives is given up by speakers of some dialects of Dutch, thus phonetically merging them into the voiceless fricative [x] or even into a more retracted, but nevertheless voiceless, uvular fricative [χ](cf. Gussenhoven 1992). Consequently, this development seemingly results in A-class vowels followed by voiceless fricatives. Nevertheless, the merger may not have taken place on the phonological level since speakers still apply the voicing contrast for the selection of the suitable past tense suffix [-də/-tə]. However, there is also a (much smaller) set of genuine exceptions containing an A-class vowel followed by a voiceless fricative (Van Oostendorp 2003;Visser 1997):

| goochem | /xoxəm/ | smart |

| sjofel | /ʃofəl/ | shabby |

| tafel | /tafəl/ | table |

| brasem | /brasəm/ | bream |

Van Oostendorp (2003:310) raises the following three questions: first, why do most exceptions involve intervocalic fricatives but less often fricatives in other positions; second, why is the set of exceptions much larger for B-class vowels followed by voiced fricatives than for A-class vowels followed by voiceless fricatives; and third, why can all exceptions of voiceless fricatives after A-class vowels only be found within morphemes and not at morpheme boundaries?

A third group of exceptions related to this observation concerns diphthongs. Whereas A-class vowels and diphthongs usually pattern together phonologically, diphthongs seem to be less compliant with respect to this particular co-occurrence restriction. As can be seen in table (1), all three diphthongs can not only be followed by voiced fricatives but also by /s/ and the diphthong /œy/ can also be followed by the voiceless velar fricative /x/ (although all those examples are scarce). Evidence for underlying voiceless fricatives comes from derived plural or past tense forms: krijs - krijste [ˈkrɛistə] screamed, kruis - kruiste [ˈkrœystə] crossed, kous - kousen and gejuich - juichen - juichte [ˈjœyxtə] cheered. The noun kous [kɑus] stocking does not show the voiced fricative in the plural form kousen [ˈkɑusə(n)] (in contrast to e.g. saus /sɑuz/ [sɑus] sauce - sauzen /sɑuzə(n)/ [ˈsɑuzə(n)] sauces). Furthermore, all the verb forms mentioned select the past tense suffix -te [-tə] (instead of -de [-də]) which is typical for voiceless obstruent final verb stems (cf. afstoffen /ɑfstɔfə(n)/ to dust - stofte af /stɔftə ɑf/ [ˈstɔftə ɑf] dusted but kleven /klevə(n)/ to stick to - kleefde /klevdə/ [ˈklevdə] sticked to).

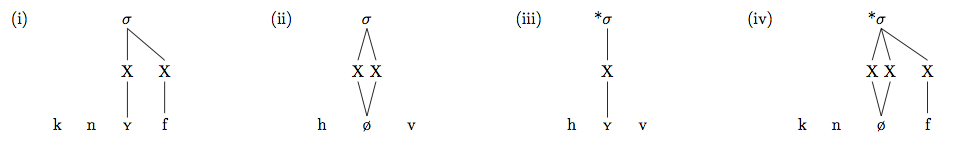

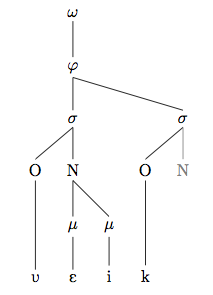

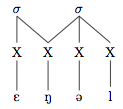

The phonological accounts for this vowel + consonant co-occurrence restriction are very limited. Van Oostendorp's (2003,2007) account rests upon the `Multiple Feature Hypothesis' (cf. Kager et al. 2007, Iverson and Salmons 1995; Avery and Idsardi 2001), i.e. that the voicing contrast only holds for Dutch stops. Van Oostendorp proposes that the contrast in Dutch fricatives is not a laryngeal contrast but a length contrast since there is phonetic evidence that phonetically voiced fricatives are considerably shorter in duration than phonetically voiceless ones. Furthermore, it is assumed that long/voiceless fricatives project one mora, while short/voiced fricatives are not moraic. In the case of vowels, it is additionally assumed that A-class vowels project two moras and B-class vowels project one mora. Combined with the presupposition that stressed syllables must minimally and maximally consist of two moras, the observed cases as depicted in (i) knuf(fel) /knʏfəl/ hug and (ii) heuv(el) /høvəl/ hill are allowed whereas the cases in (iii) huv(el) /hʏv/ and (iv) kneuf(fel) /knøf/ are prohibited because the resulting structures are either too small or too big, respectively (cf. Van Oostendorp 2007:88).

The account just presented relies on the fact that A-class vowels and B-class vowels are distinguished by whether they project one or two moras. This might be in conflict with an account that uses the featural contrast of [lax] vs. [tense] for vowels which assumes all A-class vowels and B-class vowels to project one mora. Finally, we will see below that the proposed bi-moraic minimality/maximality condition proves to be problematic when other vowel + non-fricative segment sequences are considered.

The two Dutch glides /j, ʋ/ can only occur after A-class vowels; they are usually prohibited after B-class vowels and diphthongs. /j/ can only be found after back vowels ( /uj, oj, aj/), whereas /ʋ/ occurs exclusively after front vowels ( /iʋ, yʋ, eʋ/). Examples are given in (3). The front vowel /ø/ is never followed by a glide. These vowel + glide sequences are also called pseudo diphthongs or 'fake' diphthongs.

Exceptional cases of the sequence B-class vowel + glide do occur in a small number of loanwords (4) and in the word hoi /hɔj/ hello (examples taken from Booij 1995:44).

| mais | /mɑjs/ | corn | |||

| Thais | /tɑjs/ | Thai | |||

| detail | /də.tɑj/ | (also | /də.taj/ | ) | detail |

| boiler | /bɔj.lər/ | boiler |

As a consequence of the fact that A-class vowels can be followed by maximally one consonant in the same rhyme, glides following A-class vowels cannot be followed by other consonants in the same coda. Coronals seem to be exceptional - cf. the two examples ooit /ojt/ sometime or stoeis /stujs/ frisky. However, it has been claimed that word-final coronals do not belong to the coda but instead occupy an appendix position (e.g. Moulton 1956) since they are the only consonants that can occur in (phonological) word-final extra-long consonant clusters.

Related to the last-mentioned observation is the question whether real diphthongs should be analysed as complex vowels or sequences of vowel + consonantal glide. Booij (1995:44;1989) argues for diphthongs being complex nuclei since the alternative analysis would result in difficulties in differentiating the phonotactic behavior of real diphthongs and pseudo-diphthongs. All real diphthongs can be followed by most (non-coronal) consonants (e.g. eik /ɛik/ oak, duim /dœym/ thumb, faun /fɑun/ faun), whereas pseudo-diphthongs cannot. Notice that apart from the exceptions in (4), the first element of a pseudo-diphthong must be an A-class vowel, in contrast to real diphthongs whose first element is always a B-class vowel.

In the previous paragraph we saw that diphthongs should be analysed as complex nuclei in Dutch, patterning with A-class vowels in that they allow for maximally one additional (non-coronal) coda consonant. However, additional restrictions apply to the quality of the consonants following diphthongs.

The two tables below list examples for all attested combinations of the three diphthongs and obstruent coda consonants (see 2) as well as diphthong and sonorant coda consonants (see 3). The examples marked with ** either refer to the only attested example (based on CELEX and Theissen et al. 1988) or to a very small set of examples. Since final devoicing is active in Dutch, related/derived forms are given to provide evidence for the proposed underlying forms.

| coda consonant | /ɛi/ | /œy/ | /ɑu/ |

| /p/ | pijp /pɛip/ pipe | kuip /kœyp/ tub | - |

| /t/ | mijt /mɛit/ mite | spruit /sprœyt/ shoot, sprout | hout /hɑut/ wood |

| /k/ | slijk /slɛik/ mud, slime | buik /bœyk/ stomach | pauk /pɑuk/ kettledrum |

| /b/ | - | **Huib /hœyb/ name | - |

| /d/ | tijd /tɛid/ [tɛit] time (cf. tijden [ˈtɛidə(n)] times) | bruid /brœyd/ [brœyt] bride (cf. bruiden [ˈbrœydə(n)] brides) | goud /xɑud/ [xɑut] gold (cf. gouden [ˈxɑudə(n)] golden) |

| /f/ | - | - | - |

| /s/ | **krijs /krɛis/ scream (cf. krijste [ˈkrɛistə] screamed) | **kruis /krœys/ cross (cf. kruiste [ˈkrœystə] crossed) | **kous /kɑus/ stocking (cf. kousen [ˈkɑusə(n)] stockings) |

| /x/ | - | **gejuich /xə.jœyx/ cheering (cf. juichte [ˈjœyxtə] cheered) | - |

| /v/ | olijf /o.lɛiv/ [oˈlɛif] olive (cf. olijven [oˈlɛivə(n)] olives) | druif /drœyv/ [drœyf] grape (cf. druiven [ˈdrœyvə(n)] grapes) | - |

| /z/ | prijs /prɛiz/ [prɛis] price, prize (cf. prijzen [ˈprɛizə(n)] prices, prizes) | muis /mœyz/ [mœys] mouse (cf. muizen [ˈmœyzə(n)] mice) | **saus /sɑuz/ [sɑus] sauce (cf. sauzen [ˈsɑuzə(n)] sauces |

| /ɣ/ | vijg /vɛiɣ/ [vɛix] fig (cf. vijgen [ˈvɛiɣə(n)] figs) | zuig /zœyɣ/ [zœyx] to suck (cf. stofzuigde [ˈstɔfzœyɣdə] vacuumed) | - |

| coda consonant | /ɛi/ | /œy/ | /ɑu/ |

| /m/ | rijm /rɛim/ rhyme | duim /dœym/ thumb | - |

| /n/ | termijn /tɛr.mɛin/ term, period | tuin /tœyn/ garden | **clown /klɑun/ clown |

| /ŋ/ | - | - | - |

| /l/ | zijl /zɛil/ rope | uil /œyl/ owl | **Paul /pɑul/ name |

| /r/ | - | - | - |

| /j/ | - | - | - |

| /ʋ/ | - | - | - |

A striking observation is the fact that the three (real) diphthongs in Dutch ( /ɛi, œy, ɑu/) can neither be followed by the rhotic consonant nor by any of the two glides /j, ʋ/(Booij 1995:34).

As for /r/, this means that (word-final) structures such as /ɛir, œyr, ɑur/ are not found. By contrast, if the diphthong and the rhotic consonant belong to separate syllables, diphthongs and /r/ can indeed co-occur, as exemplified by the (loan)words in (5).

Booij (1995:34, citingKoopmans-van Beinum 1969) states that homosyllabic diphthong + rhotic consonant sequences usually get resolved by schwa-epenthesis, which is the result of conflicting articulatory gestures: all Dutch diphthongs are rising diphthongs involving a rising tongue movement towards high vowel positions, which is opposed to the centralizing gesture that is necessary for the pronunciation of the rhotic consonant.

Secondly, in contrast to A-class vowels, diphthongs cannot be followed by glides. Instead of stating a constraint prohibiting any homosyllabic diphthong + glide sequence, one might propose a moraic explanation for this phenomenon. Following standard Moraic Theory (McCawley 1968;Hyman 1985;McCarthy and Prince 1986;Zec 1988,1995;Hayes 1989;Morén 1999), syllable onsets do not contribute to syllable weight, whereas nucleus and coda positions do. According to a non-length based approach distinguishing A-class vowels and B-class vowels, it is reasonable to assume that both vowel types are monomoraic (notice the difference to the proposal in the extra box above). In contrast, diphthongs, being complex nuclei, are assumed to be bimoraic structures. All coda consonants project a mora in Dutch (see extra above for a possible exception).

According to the Sonority Sequencing Principle(Clements 1990), the sonority should steeply rise for onset + nucleus sequences and mildly decrease or not decrease at all in rhymes, i.e. nucleus + coda consonants. As a consequence of the sonority hierarchy given below, obstruents ideally occur in onset positions and sonorants in coda positions.

Since glides are the most sonorous non-vowel segments, they prefer to occur in coda positions, consequently projecting a mora. It has been postulated that a bimoraic maximum restriction holds for Dutch syllables (Van Oostendorp 2004). Hence, A-class vowels can be followed by a glide within the same syllable. However, diphthongs already occupy the two available moras and therefore do not leave space for a mora-projecting glide within the same syllable.

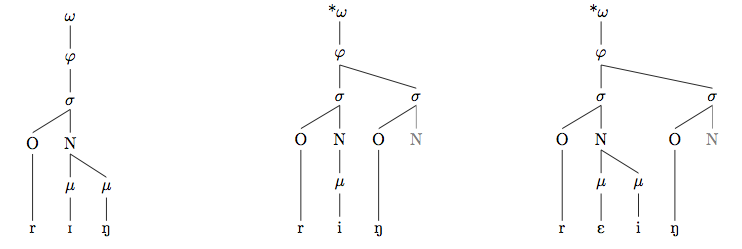

There are two questions that immediately arise: first, why can monomoraic B-class vowels apparently not be followed by glides and, second, why can bimoraic diphthongs be followed by consonants other than glides? The first problem seems to be a mere gap, probably due to diachronic language developments, since loanwords that exhibit a B-class vowel + glide sequence are easily integrated into Dutch without changing the vowel (cf. 4). The problem addressed in the second question seems more structural in nature and might again be an effect of the Sonority Sequencing Principle (see above). Whereas highly sonorous glides have a strong preference for coda positions but are dispreferred in following diphthongs within the same syllable due to the bimoraic maximum for Dutch syllables, obstruents following diphthongs can happily be assigned to the onset of a following degenerate syllable, i.e. a syllable with an empty nucleus. Notice that this account adopts a slightly different notion of syllable structure than described in phonotactics at the syllable level. The suggested syllable structure is illustrated in the following figure for the example wijk /ʋɛik/ neighbourhood. Notice that the word does begin with a glide in onset position. This is possible since the glide is attached to a strong position - word-initial position and part of an onset that is licensed by the following non-empty nucleus.

Additional support for such a proposal comes from words containing intervocalic glides. Compare the two words bouw [bɑu] construction (industry) and bouwen [ˈbɑu.ʋə(n)] to build. Whereas in the former word the word-final glide does not surface after the diphthong (it is not licensed in the onset of an empty-headed syllable and therefore unpronounced/deleted), the glide in intervocalic position does surface since its onset position is licensed by the following nucleus containing schwa.

Although this account might appear stipulative at first sight, it makes correct predictions when considering segments of decreasing sonority. Analogously to glides, rhotic consonants are not allowed after diphthongs. So, the claim would be that rhotic consonants cannot occur in onsets of empty-headed syllables either (cf. examples in 5; but raar [rar] weird). In contrast, the less sonorous class of laterals as well as all other even less sonorous consonants are allowed in onsets of empty-headed syllables and therefore can follow diphthongs (cf. zijl /zɛil/ rope, uil /œyl/ owl, Paul /pɑul/ name).

The velar nasal /ŋ/ does not occur in syllable onsets in Dutch. Due to the fact that A-class vowels and diphthongs may occur in open syllables and taking into account the Maximal Onset Constraint, any word-medial velar nasal following an A-class vowel or diphthong would have to be syllabified into the onset of a syllable, a position in which it is not allowed. Therefore, A-class vowel/diphthong + velar nasal sequences in word-medial position do not occur (6a). In contrast, since B-class vowels can only occur in closed syllables, a word-medial velar nasal following a B-class vowel needs to be assigned to the coda position as well, i.e. it is ambisyllabic (see figure below). As a result, such a sequence is allowed in Dutch and can be found for all B-class vowels (6b). Notice that for intervocalic velar nasals the second vowel is restricted to schwa.

Word-finally, the velar nasal /ŋ/ can be found following B-class vowels since the nasal is assigned to the coda position (7a). In contrast, word-final A-class vowel/diphthong + velar nasal sequences cannot be found (7b). The fact that A-class vowels and diphthongs can indeed be followed by word-final bilabial and coronal nasals (8a-b) indicates that the velar nasal restriction does not hold for nasals in general. Furthermore, the fact that A-class vowels and diphthongs can also be followed by a more sonorous (compared to nasals) word-final lateral (8c) suggests that the restriction holding for velar nasals might be structurally motivated.

Trommelen (1984) provides an overview of traditional accounts concerning the velar nasal restriction. One approach considers the velar nasal [ŋ] as a phonological cluster consisting of a (velar) nasal and a velar obstruent /ŋg/(see Moulton 1962:303;Leys 1970). From the examples (a-c) in table (4) below one could assume that the velar nasal behaves as a single consonant and patterns with the other nasals. However, the examples in table (4d-g) illustrate that this is not the case. Instead it seems that the velar nasal behaves similarly to consonant clusters (see 4h-k) (all examples are taken from Trommelen 1984:158). So, proponents of the cluster approach argue that the `velar nasal cluster' patterns with other homorganic consonant clusters, as shown in table (5). Leys (1970) adds supporting evidence with the alternations koning [ˈkonɪŋ] king vs. koninklijk [ˈkonɪŋklək] king-like and oorsprong [ˈorsprɔŋ] origin vs. oorspronkelijk [orˈsprɔŋkələk] original.

| a. | ram /rɑm/ ram | ven /vɛn/ fen | rang /rɑŋ/ rank |

| b. | ramp /rɑmp/ disaster | vent /vɛnt/ fellow | rank /rɑŋk/ slender |

| c. | emmer /ɛmər/ bucket | kennel /kɛnəl/ (dog) kennel | engel /ɛŋəl/ angel |

| but: | |||

| d. | vaam /vam/ fathom | vaan /van/ banner | *vaang /*vaŋ/(after long vowels) |

| e. | kerm /kɛrm/ moan | kern /kɛrn/ core | *kerng /*kɛrŋ/(2nd member in cluster) |

| f. | map /mɑp/ file | nap /nɑp/ bowl | *ngap /*ŋɑp/(initially) |

| g. | smak /smɑk/ smack | snak /snɑk/ crave | *sngak /*sŋɑk/(initially preceded by s) |

| and: | |||

| h. | *vaamp /*vamp/ | *vaank /*vaŋk/ | *vaang /*vaŋg/ |

| i. | *kermp /*kɛrmp/ | *kernk /*kɛrŋk/ | *kerng /*kɛrŋg/ |

| j. | *mpap /*mpɑp/ | *nkap /*ŋkɑp/ | *ngap /*ŋgɑp/ |

| k. | *smpak /*ampɑk/ | *snkak /*sŋkɑk/ | *sngak /*sŋgɑk/ |

| ramp /rɑmp/ disaster | rank /rɑŋk/ slender | rang /rɑŋg/ [rɑŋ] rank |

| amper /ɑmpər/ barely | anker /ɑŋkər/ anchor | angel /ɑŋgəl/ [ˈɑŋəl] hook |

Alternatively, Trommelen (1984), Cohen (1961) and Robinson (1972) argue for a single underlying consonant. First, the second member of a /ng/ŋg/ cluster is not a native segment of Dutch. Further convincing evidence comes from minimal pairs and the selection of the diminutive suffix (see table 6), in which the velar nasal behaves like a single consonant.

| ram-metje ram-DIM | Mokum-pje city name | wigwam-metje - wigwam-pje wigwam-DIM |

| man-netje man-DIM | heiden-tje heathen-DIM | python-netje - python-tje python-DIM |

| bal-letje ball-DIM | druppel-tje drop-DIM | serval-letje - serval-tje cat-DIM |

| kar-retje cart-DIM | werker-tje worker-DIM | - |

| rang-etje rank-DIM | houding-kje attitude-DIM | sarong-etje - sarong-kje sarong-DIM |

So far we have established that the velar nasal is a single consonant that is restricted to coda positions within a syllable. Lastly, we need to explain why the velar nasal can follow a B-class vowel but cannot follow either A-class vowels or diphthongs. Applying a non-length-based approach to distinguishing Dutch vowels, one is confronted with the problem that monomoraic B-class vowels pattern differently from monomoraic A-class vowels and bimoraic diphthongs. So, a solution to this problem cannot be found in a minimum/maximum restriction on rhymes. Instead we refer to Van Oostendorp (1995;2000) and the syllable theory presented there. The crucial idea is that vowels specified by the feature [lax], i.e. B-class vowels, enforce a branching rhyme structure (see also rhymes), whereas vowels lacking this feature do not. Applied to the velar nasal restriction problem at hand, this gives the desired result. All B-class vowels call for a coda position which can be filled by the velar nasal. Following a non-lax vowel, i.e. an A-class vowel or diphthong, the velar nasal would be assigned to the onset position of a following degenerate syllable, which is impossible. The following representations illustrate the described scenario.

- 2001Laryngeal dimensions, completion and enhancementHall, Tracy A. (ed.)Distinctive Feature TheoryBerlinMouton de Gruyter41--69

- 1989On the representation of diphthongs in FrisianJournal of Linguistics25319-332

- 1995The phonology of DutchOxfordOxford University Press

- 1995The phonology of DutchOxfordOxford University Press

- 1995The phonology of DutchOxfordOxford University Press

- 1995The phonology of DutchOxfordOxford University Press

- 1990The role of the sonority cycle in core syllabificationPapers in Laboratory Phonology1Cambridge University Press283-333

- 1961Fonologie van het Nederlands en het Fries. Inleiding tot de moderne klankleerMartinus Nijhoff

- 1972Fonologie van het Nederlands en het Fries. Inleiding tot de moderne klankleerMartinus Nijhoff

- 1992DutchJournal of the International Phonetic Association2245-47

- 1989Compensatory Lengthening in Moraic PhonologyLinguistic Inquiry20253-306

- 1985A theory of phonological weightDordrechtForis. (Reprinted by CSLI, Stanford University, 2003)

- 1995Aspiration and laryngeal representation in GermanicPhonology12369-396

- 2007Representations of [Voice]: Evidence from aquisitionWeijer, Jeroen M. van de & Torre, Erik Jan van der (eds.)Voicing in Dutch: (de)voicing - phonology, phonetics, and psycholinguisticsAmsterdam/PhiladelphiaJohn Benjamins Publishing Company

- 1969Nog meer fonetische zekerhedenUniversiteit van AmsterdamInstituut voor Fonetische Wetenschappen

- 1970The phonemic status of ng and the existence of a phoneme /g/ in DutchLeuvense Bijdragen59128-136

- 1970The phonemic status of ng and the existence of a phoneme /g/ in DutchLeuvense Bijdragen59128-136

- 1986Prosodic Morphology

- 1968The Phonological Component of a Grammar of JapaneseMonographs on Linguistic Analysis 2The HagueMouton

- 1999Distinctiveness, coercion and sonorty: a unified theory of weightUniversity of MarylandThesis

- 1956Syllable nuclei and final consonant clusters in GermanFor Roman Jakobson: Essays on the occasion of his sixtieth birthdayMouton

- 1962The vowels of Dutch: phonetic and distributional classesLingua11294-312

- 1995Vowel Quality and Phonological ProjectionTilburg UniversityThesis

- 2000Phonological ProjectionNiemeyer

- 2003Ambisyllabicity and Fricative Voicing in West Germanic DialectsThe syllable in optimality theoryCambridge; New YorkCambridge University Press

- 2003Ambisyllabicity and Fricative Voicing in West Germanic DialectsThe syllable in optimality theoryCambridge; New YorkCambridge University Press

- 2003Ambisyllabicity and Fricative Voicing in West Germanic DialectsThe syllable in optimality theoryCambridge; New YorkCambridge University Press

- 2004Phonological recoverability in dialects of Dutch

- 2007Exceptions to final devoicingVoicing in DutchAmsterdam/PhiladelphiaJohn Benjamins Publishing Company

- 2007Exceptions to final devoicingVoicing in DutchAmsterdam/PhiladelphiaJohn Benjamins Publishing Company

- 1972Synchronic reflexes of diachronic phonological rulesCornell UniversityThesis

- 1988Invert woordenboek van het NederlandsLiegeC.I.P.L.

- 1988Invert woordenboek van het NederlandsLiegeC.I.P.L.

- 1984The Syllable in DutchDordrechtForis

- 1984The Syllable in DutchDordrechtForis

- 1984The Syllable in DutchDordrechtForis

- 1997The Syllable in FrisianVrije Universiteit AmsterdamThesis

- 1988Sonority Constraints on Prosodic StructureStanford UniversityThesis

- 1995Sonority Constraints on Syllable StructurePhonology1285- 129