- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

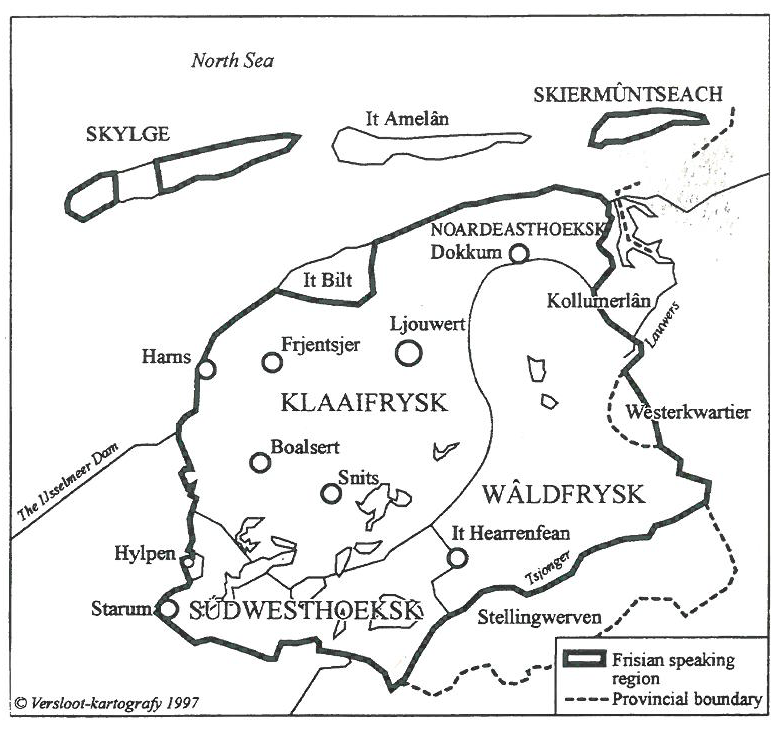

Frisian is a West Germanic language which is spoken in Fryslân, one of the twelve provinces of the Netherlands. It is spoken by approximately 450.000 people. Most inhabitants of Fryslân, approximately 94%, can understand Frisian. Around 74% of the population is able to speak Frisian. Frisian has been recognized officially as the second language of the Netherlands in the province of Fryslân. It has a standardized spelling (see taalweb) and it is used in several domains of Frisian society. Frisian commands a relatively strong position in the domains of family, work and the village community. The use of Frisian is fairly limited in the more formal domains of education, media, public administration and law. Speakers of Frisian may find themselves in a situation of "competing bilingualism". In theory, there is institutional support for scientific research on Frisian, since the Dutch government ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages with respect to Frisian. By doing so, it recognized Frisian as a minority language and it commited itself to the moral, though not legal, responsibility to preserve and reinforce the Frisian language. There are three major dialects: Klaaifrysk Clay Frisian, Wâldfrysk Forest Frisian and Súdwesthoeksk Southwestern variety. In addition, there are some smaller dialects of West Frisian. The province of Fryslân harbours not only dialects of Frisian but also a number of Frisian-Dutch and Frisian-Saxon contact variaties. They are all mutually comprehensible. Taalportaal describes the grammar of Standard Frisian, which is mainly based on Clay Frisian.

Frisian is a West Germanic language which is spoken in Fryslân, one of the twelve provinces of the Netherlands. The province is located in the north-west, and it borders on the North Sea. Fryslân has 620.000 inhabitants. It is known from representative sample surveys that approximately 94% of the population can understand Frisian, 74% is able to speak it, 65% can read it and 17% can write it. A substantial part, approximately 19%, must be second-language learners, because Frisian is the mother tongue of 55% of the inhabitants of Fryslân. Currently, just over half of the population speaks Frisian regularly at home. Over the last fifty years there has been an increase in reading and writing abilities. Overall the percentages have been relatively stable over the last fifty years. As a rule, all inhabitants of Frisia are able to speak, read and write Dutch (disregarding a very small percentage of illiterates), but about 60% of the Frisian speakers claims to have greater fluency in Frisian than in Dutch.

Frisian commands a relatively strong position in the domains of family, work and the village community. The use of Frisian is limited in the more formal domains of education, media, public administration and law, although it has made some progress during the last decades. Speakers of Frisian may find themselves in a situation of "competing bilingualism". Survey research on language use shows that the language of an interlocutor is an important factor for language choice. If the interlocutor is Dutch speaking, then Frisian people tend to accommodate to Dutch. Frisian is only spoken to Frisian speakers. Between strangers, Dutch is the unmarked, safe choice. Literature: Gorter (2001).

There are basically two kinds of dialects in the province of Fryslân. On the one hand there are three main dialects (Klaaifrysk, Wâldfrysk and Súdwesthoeksk), and a number of smaller ones. On the other hand, there are a number of Dutch-Frisian contact varieties, each with its own unique character.

The West Frisian speech community is basically homogeneous and all the dialect varieties are mutually comprehensible. The three major dialects are called Klaaifrysk Clay Frisian, Wâldfrysk Forest Frisian and Súdwesthoeksk Southwestern variety. Speakers of Clay Frisian speak with a drawl, producing longer vowel sounds and diphthongs. Speakers of Forest Frisian tend to speak faster, they have a different form of breaking and they have a characteristic, short pronunciation of the personal pronouns. The third major dialect, Southwestern, is spoken, unsurprisingly, in the south-western corner of the province. It differs from the other varieties in its own particular pronunciation, lacking the phonological feature of breaking, but reproducing the morphological function of breaking by means of an extra phoneme, which is absent in the other Frisian dialects. The standard variety of West Frisian is mainly based on Clay Frisian, but without the drawl. Taalportaal describes the grammar of the standard variety, but sometimes provides additional information on Frisian dialects.

Minor Frisian dialects are spoken in relatively isolated areas close to the sea. Skiermûntseagersk is spoken on the island of Skiermuontseach (Dutch: Schiermonnikoog). The island of Skylge (Dutch: Terschelling) features two Frisian dialects, Westersk and Aastersk. At the north-eastern border of the province a local dialect known as Kollumersk is spoken, which has some features in common with the adjacent dialects of the province of Groningen.

During the the first part of the 16th century, a separate linguistic system emerged in at least eight towns, the so-called Stedsfrysk Town Frisian (see Bree (2008)). This dialect emerged due to the presence of a Dutch elite, consisting of immigrant civil servants and rich traders. A substantial part of Frisian natives acquired Dutch inadequately as a second language, mixing with the elite and producing Town Frisian. As a result, Town Frisian can be informally characterised as Dutch with Frisian substrate: it sounds Dutch, but it has Frisian characteristics in its emotional and specialist vocabulary, in its unaccented morphology and in its syntax, that is, those aspects of language which users are less aware of. The emergence of Town Frisian led to a contrast between the towns and the countryside, which is reflected in the distribution of Frisian. In the countryside 70% of the population has Frisian as its home language and in the larger cities this is only 40% percent or less. In the course of time, Town Frisian became a characteristic of low class speech, whereas the elite began to speak perfect Dutch.

Another Dutch-Frisian contact variety is Midslânsk, spoken in Midslân (Dutch: Midsland), the capital of the isle of Terschelling. And yet another contact variety is spoken in the area of It Bilt. This area was reclaimed from the sea around 1600 by inhabitants of the provinces of North and South Holland. As a result, a contact variety came into existence, Biltsk, which sounds Dutch, but which displays some morphological and syntactic characteristics of Frisian (Koldijk (2004)). Furthermore, a Saxon-Frisian contact dialect is spoken in the South of the province. It is called Stellingwerfsk and it is spoken by about one third of the inhabitants of the region (around 20.000 people) (Bloemhof (2002)).

The dialects of the province of Groningen can be loosely defined as Saxon dialects with a Frisian substrate (Hoekstra (2001)), which are quite similar to the type of Low German spoken on the other side of the Dutch-German border. The Groningen dialects came into existence when the inhabitants of the countryside switched from Frisian to Low German in the 14th century (Huizinga (1914)).

Historically, all Frisian dialects derive from Old Frisian. Around the year 700, it was spoken in the coastal area between Rotterdam and Bremen, as is shown on the following map.

Needless to say, this area was much less densely populated than it is today. Frisian was quickly wiped out in the province of South Holland after the defeat of the Frisian king Redbad (Dutch: Radboud) in the first quarter of the 8th century. The present-day dialects of the province of North Holland still contain linguistic traces which are reminiscent of Frisian. The Frisian evidence is most conspicuous in place names, field names and water names, but some of the dialects still show the presence of Frisian substrate in their vocabulary, their morphology and their syntax (Hoekstra (2001)).

Frisian as spoken in The Netherlands is sometimes referred to as West Frisian, to distinguish it from the two other Frisian languages, which are spoken in Germany: North Frisian and East Frisian. They are not mutually understandable. As a result, Frisian can be viewed as a language family consisting of three branches. Note that, within The Netherlands, Westfries (West-Frisian) is used to refer to a dialect spoken in the province of North Holland. This is a Dutch dialect with a Frisian substrate dating back to the time (early Middle Ages) when Frisian was spoken in North Holland.

North Frisian is a cover term for nine dialects, which can be divided in mainland dialects (the dialects of Wiedingharde, Bökinghardem, Karrharde, Norder- and Mittelgoesharde, Halligen) and insular dialects (the dialects of Sylt, Föhr, Amrum and Helgoland) (Walker (2001)). Some of these dialects are to a certain degree mutually incomprehensible. North Frisian is spoken by around 8.000 speakers, but there are no exact surveys (Walker (2001)). All people in North Frisia are bilingual, trilingual or even quadrilingual. Five languages are spoken in North Frisia: Frisian, Low German, High German, Jutish and Danish. North Frisian is a endangered (just as Jutish and Low German) language as the percentage of speakers in the younger generations is decreasing rapidly. The North Frisian area was settled by Frisian in two waves of migration, in the 8th century and in the 11th century (Århammar (2001)).

East Frisian was once spoken in the area roughly defined by the cities Bremen and Oldenburg and the Dutch-German border. In the course of the Middle Ages, East Frisian gradually gave way to Low German, as also happened in the Dutch province of Groningen. Nowadays, East Frisian consists of one last living dialect: Sater Frisian. It is spoken in the Saterland area, in the former state of Oldenburg. Sater Frisian is spoken by approximately 2.500 people, the majority of them elderly people. Sater Frisian is therefore seriously endangered (Ford (2001)).

Frisian has been officially recognized as the second language of the Netherlands within the province of Fryslân. It has a standardized spelling (see taalweb) and it is used in several domains of Frisian society. There is institutional support for scientific research on Frisian, since the Dutch government ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages with respect to Frisian. By doing so, it recognizes Frisian as a minority language and it commited itself to the moral, though not legal responsibility to preserve and reinforce the Frisian language. One of the spearheads of language policy is education. Frisian has a modest place in the education system. Since 1980 the language became an obligatory part of the curriculum in all primary schools. Time devoted to Frisian is limited and does mostly not exceed 36 minutes per week. Currently, there are trilingual schools, using Frisian as a medium of instruction besides Dutch and English.

Pre-schoolers often go to playgroups. The Stifting Frysktalige Berneopfang Foundation for child care in Frisian is responsible for running Frisian and bilingual playgroups. Child care is meant for children between two and a half and four years old. This foundation has an explicit language policy and aims to establish a Frisian-speaking environment for young children. In secondary education Frisian is an obligatory subject in the lower grades. It is sometimes an optional exam subject in the higher grades. The attainment targets for the lower grades differentiate between students which have Frisian as their mother tongue and those who do not. In vocational education Frisian has no formal position in the curriculum, but it is regularly used as a medium of instruction and it sometimes is an optional subject. When it comes to higher education, the University of Groningen offers a study programme Minorities and Multilingualism with a specialization track in Frisian language and culture. A teacher-training Master's degree (120 ECTS) is also available there. The Department of Dutch Studies of the University of Amsterdam offers a full minor (30 ECTS) as well as some master courses in Frisian language and literature. At Leiden University Frisian can be taken as an additional subject.

Teacher training for the primary level is provided by the Stenden Hogeschool and the NHL Hogeschool, both situated in Leeuwarden, which is the capital of Fryslân. Training for the secondary level is also provided by the NHL Hogeschool.

There is a covenant between the Province and the State Government which includes provisions for Frisian media, education, culture and scientific research on Frisian, but also for public administration and the use of Frisian in court. The Province and a number of municipalities make use of both written and spoken Frisian in public administration. The two major daily newspapers contain some Frisian every day, mainly in quotes, although the actual percentage measured in words is very small (less than 3%). Furthermore, articles written in Frisian often have no news value (De Schiffart (2009)). The regional broadcasting company transmits radio and television broadcasts mostly in Frisian.

In Fryslân there are several institutions dedicated to the advancement of the Frisian language. One of these is the Fryske Akademy Frisian Academy, which is the scientific research center of Fryslân for the Humanities, researching the Frisian language, culture, history and society. Among other things, linguists of the Fryske Akademy compiled a dictionary of the Frisian language in 25 volumes, also available on the internet (WFT). The goal of the AFÛK-foundation is to promote the knowledge and use of the Frisian language as well as promoting the interest in Fryslân and its culture. Employees of the AFÛK organize courses in Frisian for both non-Frisian speakers as well as Frisian speakers. The foundation It Fryske boek The Frisian Book' is concerned with promoting books written in Frisian.

Frisian linguistics has a small institutional infrastructure. In fact, there is only a handful of researchers occupied with Modern Frisian linguistics. On a European scale there are five people working full time on it. These researchers mainly work at the Linguistic Department of the Fryske Akademy Frisian Academy. Besides that, there is academic staff for Frisian linguistics at the University of Groningen (RUG), Leiden University (UL) and at the University of Amsterdam (UvA). In Kiel, Germany, there is one professor working full-time on Frisian. Although his teaching commitment is primarily directed towards North Frisian, he in fact directs a great deal of his research towards Frisian Linguistics. Frisian linguistics has a contrastive character, focusing on differences between Dutch and Frisian.

The Fryske Akademy Frisian Academy is associated with The Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW). Since its foundation in 1938 the Frisian Academy has occupied a central place in research on the Frisian language, history and society. Important projects concern linguistics and lexicography, history and social sciences. The latter is mainly concerned with the sociology of language, international comparative research on other European minority languages, especially in the field of education within the framework of the Mercator project. Since its inception the Frisian Academy has published over 1000 books in many different languages, of which one third in Frisian, one third in Dutch and one third is in English and German.

- 2002Taal in stad en land - StellingwerfsSdu Uitgevers

- 2008Oorsprongen van het StadsfriesAfûk

- 2001Das SaterfriesischeMunske, Horst Haider (ed.)36Max Niemeyer Verlag409-422

- 2001Verbreitung und Geltung des WestfriesischenMunske, Horst Haider, Århammar, Nils, Hoekstra, J.F., Vries, O., Walker, A.G.H., Wilts, O. & Faltings, V.F. (eds.)Handbuch des FriesischenMax Niemeyer73-83

- 2001Frisian Relics in the Dutch DialectsMunske, Horst Haider (ed.)17Max Niemeyer Verlag138-142

- 2001Frisian Relics in the Dutch DialectsMunske, Horst Haider (ed.)17Max Niemeyer Verlag138-142

- 1914Hoe verloren de Groningse Ommelanden hun oorspronkelijk Fries karakter?Driemaandelijkse Bladen141-77

- 2004Het Bildts, zijn wezen, herkomst en problematiek. Een dialectgeografisch en historisch onderzoekFryske Akademy

- 2009Frysk nijs is Fryskfrjemd. In ûndersyk nei it Fryske taalbelied fan de Leeuwarder Courant en it Friesch DagbladRijksuniversiteit GroningenThesis

- 2001Die nordfriesischen MundartenMunske, Horst Haider, Århammar, Nils, Hoekstra, J.F., Vries, O., Walker, A.G.H., Wilts, O. & Faltings, V.F. (eds.)Handbuch des FriesischenMax Niemeyer284-304

- 2001Extent and Position of North FrisianHandbuch des FriesischenNiemeyer

- 2001Die Herkunft der Nordfriesen und des NordfriesischenMunske, Horst Haider (ed.)50Max Niemeyer Verlag531-537