- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Finite interrogative complement clauses in Afrikaans have the same syntactic distribution as finite declarative complement clauses. They are linked to matrix clauses in the position of object, subject or complementive. General and specific interrogative clauses also have similar distributions, although specific interrogative clauses are more frequent in all positions, and consequently show more variability and also more discernible patterns of association, as is explained in the section on lexical and semantic associations.

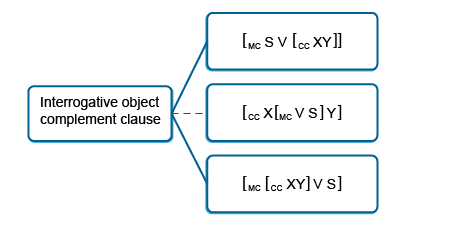

The finite interrogative object clause mainly occurs in clause-final position, after the matrix clause, as in example (1). It can, like its declarative counterpart, also be found in the clause-initial position, as in example (2), which is attested in very low frequencies in the Taalkommissiekorpus. It is not clear if the matrix clause can be embedded as fragment within the complement clause, as in example (3a) and (3b), since such instances are unattested in the samples of the corpora available for analysis. The exception is (3b'), which is attested in extremely low frequencies in the data, where main clause rather than subordinate clause word order is used, and where the “matrix clause” functions as an adverbial rather than a main clause.

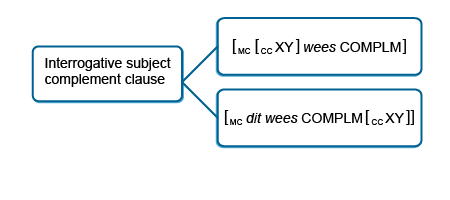

Finite interrogative subject clauses occur more frequently in the dit-extraposition construction, as in example (4), or else in clause-initial position, as in example (5).

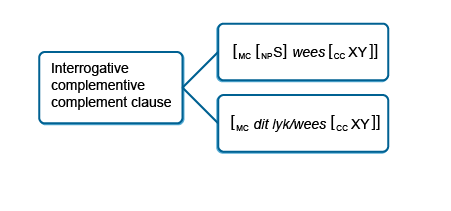

Finite interrogative complement clauses can also be used as the complementive predicate in a copular construction, mainly after the verb is be.PRS is or lyk to appear, with limited syntactic variation, as in example (6).

The overall frequency of interrogative complement clauses in the three major syntactic functions are summarised in Figure 4, based on an analysis of the Taalkommissiekorpus.

Compared to declarative complement clause constructions, the interrogative counterparts are consistently less frequent. Interrogative object clauses are almost 6 times less frequent than declarative object clauses, while interrogative subject clauses are 4 times less frequent than declarative subject clauses. However, interrogative complementive predicate clauses are only 1,16 times less frequent.

Interrogative object clauses, like their declarative counterparts, can occur after (clause-finally) or before the matrix clause (clause-initially), as is illustrated by the examples in (1) and (2). The matrix clause can also be inserted parenthetically in the object clause, as in (3bi), but it is not possible in Afrikaans to do so with complement clauses that have subordinate word order – only independent clause interrogative order can be used, which clearly demonstrates that this syntactic pattern does not involve a main clause-subordinate clause relationship. Rather, the complement-taking predicate functions as a genuine parenthetical insertion, and not as a matrix clause for the subordinate clause. Further examples similar to (3bi) are given in (7). Note the repetition of the complete interrogative with independent word order in (7b).

The clause-final position, however, dominates, even compared to the declarative object complement clause variant. As far as specific interrogatives is concerned, the clause-initial position is selected in almost 1,5% of the analysed sample from the TK and the parenthetical insert variant in only 0,08%, leaving the balance of 98,5% of the sample for the clause-final position. In the case of general interrogatives, the final position accounts for 98% of all cases and the initial position for the remaining 2%.

Differences in syntactic distribution are therefore not very productive for the interrogative object clause construction. The few attested cases of the clause-initial variant are mostly from the fiction and newspaper registers (as is the case with the declarative clause counterpart) and can be seen as an extension of an option that is more productive for the declarative complement clause construction, and not very salient or entrenched for the interrogative complement clause. Example (8) and (9) from these registers illustrate the use of the clause-initial variant.

| Fiction | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | Wat die spieël my vertel het, kon ek ook in Karel se oë gewaar toe ons terugkom in die kombuis. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| what the mirror me tell.PST have.AUX can.AUX.MOD.PRT I also in Karel PTCL.GEN eyes notice.PRS when we return.PRS in the kitchen | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| What the mirror told me, I could also sense in Karel's eyes when we returned to the kitchen. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [TK] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Of Cox 'n sê oor dié goed gehad het, het hy nie geweet nie. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| if Cox a say about this stuff have.PST have.AUX have.AUX he not know.PST PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Whether Cox had a say about these things, he did not know. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [TK] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| News reportage | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | Wat het hy vir die meisie gedoen, wou mense by hom weet. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| what have.AUX he for the girl do.PST want.to.AUX.MOD.PRT people from him know.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| What did he do for the girl, people want to know from him. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [TK] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Óf ons eendag daarby sal uitkom, weet ek nie... | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| if.COMP we one.day there.at will.AUX.MOD out.come.INF know.PRS I not | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| If we will get to this one day, I don't know... | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [TK] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The interrogative subject clause in Afrikaans has not been subject to any serious scholarly investigation. Ponelis (1979) discusses subject clauses in general, and offers an overview of the two major syntactic variants, namely the extraposition variant and the clause-initial variant. His examples include interrogative subject clauses, but he says little about the syntactic properties of the construction, and equally little about differences in syntactic distribution between the general and specific interrogatives.

The most salient characteristic of the matrix clause that distinguishes between the use of the declarative and interrogative subject clause is the presence of negation. Negation is expressed either by means of a syntactic negation construction, as in example (10), a negative prefix attached to the adjective complementive of the clause, as in example (11), or by selecting a complementive that has the meaning of doubt or some other negative prosody, as in example (12).

| Of dit Van Zijl se waens was, is nie bekend nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| if.COMP it Van Zijl PTCL.GEN trucks be.PRT be.PRS not know.PST.PTCP PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Whether it was Van Zijl's trucks is not known. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Syntactic negation] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit is volgens Transnet nog onduidelik hoekom die laaier gebreek het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it be.PRS according.to Transnet still unclear why the loader break.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It is still unclear, according to Transnet, why the loader broke. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Morphological negation] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Of dit enigsins gaan help om die Wêreldbeker te wen, is te betwyfel. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| if.COMP it at.all go.LINK help.INF for.COMP the World.Cup PTCL.INF win.INF be.PRS PTCL.INF doubt.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| If it is at all going to help to win the World Cup is doubtful. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [Negative prosody] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

General interrogative subject clauses are infrequent in Afrikaans. Both the extraposition and clause-initial variants are available and attested in the data, as illustrated by (4a) and (5a). While the extraposition variant is attested slightly more frequently in the data, the difference is much smaller than for any other subject clause constructions (declarative, specific interrogative or infinitive). The data do not yield any clear evidence of syntactic differences between the two variants. Thus, matrix clauses are generally not syntactically more complex in the case of the clause-initial variant, as might be motivated by considerations of end-weight or processability. In fact, the vast majority of matrix clauses in the data for both variants are short and syntactically very simple. The most typical pattern is a copular construction with the copular verb is be.PRS is and an adjective that is either negated by nie not or contains a negative prefix, usually on-, as is illustrated by examples (13) and (14).

Alternatively, other verbs are used, but drawn from a fairly limited pool of options of a relatively fixed idiomatic nature, as is illustrated by afhang down.hang depend on in (15) and saakmaak concern.make matter in (16). The section on lexical associations provides more detail about these verbs.

What is particularly interesting about these verbs, as supporting evidence for their status as fixed expressions, is the extent to which they display reduction, by omitting the anticipatory pronoun dit it, and in the case of example (17) below, even the copular verb. Examples of such omission are the following:

| So ampertjies of ek sê hardop dankie vir die trekkie vars lug. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| so almost.DIM if.COMP I say.PRS aloud thank.you for the draw.DIM fresh air | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| So close or I said thank-you out loud for the breath of fresh air. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maak nie saak of hy gelukkig of ongelukkig is nie, die blik moet oop, die aartappels moet afgeskil en opgesit word, hy moet eet. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| make.PRS not concern if.COMP he happy or unhappy be.PRS PTCL.NEG the tin must.AUX.MOD open.PREP the potatoes must.AUX.MOD off.peel.PASS and on.put.PASS be.AUX.PASS.INF he must.AUX.MOD eat.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Doesn't matter whether he is happy or unhappy, the tin must be opened, the potatoes must be peeled and prepared, he has to eat. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hang af of die aandwind genoeg gaan wees om ons buite op die oopsee te kry. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| depend off if.COMP the evening.wind enough go.LINK be.INF for.COMP us outside on the open.sea PTCL.INF get.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Depends if the evening wind will be enough to get us out to the open sea. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This feature occurs in standard written Afrikaans, although often in fictional dialogue, where the writing pretends to simulate speech or the inner monologue of characters. This is the case even though the general interrogative subject clause construction itself is even rarer in spoken than written Afrikaans.

The specific interrogative subject clause construction is considerably more frequent in Afrikaans than the general interrogative, and also has a wider range of meanings: epistemic, evaluative and importance, as is shown in the section on lexical associations. Syntactically, however, the constructions are quite similar, except that the association with negation is much stronger with epistemic meanings, and not so prominent with the other meanings of the construction. For all three types of meanings, the more frequent syntactic construction is the extraposition construction, as exemplified in (4b), while the clause-initial variant, exemplified in (5b) is considerably less frequent.

The extraposition construction mainly has a copular verb with an adjective as complementive, whether this adjective is negated or not. The verb is is is by far the dominant copular verb, with a very small number of other verbs, including word to become, blyk to appear and bly to remain also attested. Examples of this pattern are the following:

| Dis duidelik waarom Kobus so 'n sukses van hierdie onderneming gemaak het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it=be.PRS clear why Kobus such a success of this undertaking make.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It's clear why Kobus made such a success of this undertaking. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nou is dit vir haar glashelder waarom Vogelsang onder die hamer gekom het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| now be.PRS it for her glass.clear why Vogelsang under the hammer come.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Now it is crystal clear to her why Vogelsang came under the hammer. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit is onverklaarbaar hoekom hy sy benadering vir die Wêreldbeker verander het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it be.PRS inexplicable why he his approach for the World.Cup change.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It is inexplicable why he changed his approach for the World Cup. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... dis nie seker waarom die helikopter neergestort het nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it=be.PRS not certain why the helicopter down.fall.PST have.AUX PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It is not certain why the helicopter crashed. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Uit die bespreking het dit geblyk hoe moeilik dit is om Galasiërs 3:10 te interpreteer. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| from the discussion have.AUX it appear.PST how difficult it be.PRS for.COMP Galatians 3:10 PTCL.INF interpret.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| From the discussion it became evident how difficult it is to interpret Galatians 3:10. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hieruit word dit duidelik waarom dit noodsaaklik is dat Paulus ook Rome moet besoek om die evangelie te verkondig. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| here.out become it clear why it necessary be.PRS COMP Paul also Rome must.AUX.MOD visit.INF for.COMP the gospel PTCL.INF preach.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| From this it becomes clear why it is essential that Paul must also visit Rome to spread the gospel. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The omission of the dummy subject and copular verb of the matrix clause is also attested, with only the complementive predicate remaining, still introducing the specific interrogative subject clause. This option is mainly attested with evaluative meanings, as is shown by the following examples:

| Snaaks hoe hy aanmekaar beroepe na ander gemeentes kry wat blykbaar behoefte het aan sy besondere talent. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| funny how he continuously callings to other congregations receive.PRS which apparently need have.PRS for his special talent | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Funny how he is always being called to other congregations that apparently have a need for his special talent. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ongelooflik hoe 'n enkele kleur 'n hele atmosfeer kan herroep! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| incredible how a single colour a whole atmosphere can.AUX.MOD recall.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Incredible how a single colour can recall an entire atmosphere! | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A much smaller number of cases show the use of another verb in the matrix clause. Similar to the general interrogative subject clause construction, these verbs usually come in the form of relatively fixed phrases. The most prominent of these expressions is dit maak nie saak … nie it doesn't matter, while expressions like kleinkry small.get to grasp, dit skiet X te binne it shoots X to inside it strikes X and traak to bother are also found. In the case of dit maak nie saak … nie, the omission of the dummy pronoun dit it is widespread. These options are illustrated by the following examples:

| ... dit maak nie saak hoe dit lyk of wat daarin staan nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it make.PRS not concern how it look.PRS or what there.in stand PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ...it doesn't matter what it looks like or what is said in it. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... …maak nie saak hoe goed of sleg dit inpas by heersende politiek en emosies nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| make not concern how well or poorly it in.fit.PRS with reigning politics and emotions PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... doesn't matter how well or poorly it suits current politics and emotions. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek kan dit nou nog nie kleinkry hoe hy net twee geel kaarte aan die opponente gewys het nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I can.AUX.MOD it now still not small.get.INF how he only two yellow cards to the opponents show.PST have.AUX PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I still don't get how he only showed two yellow cards to the opponents. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit skiet haar te binne wie haar al weer as 'n Jesebel uitkryt: haar loerende bure. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it shoot.PRS her to inside who her yet again as a Jezebel out.cry.PRS her peeping neighbours | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It strikes her who is yet again denouncing her as a Jezebel: her peeping neighbours. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit traak hom in elk geval min wat Le Roux sê. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it bother.PRS him in any case little what Le Roux say.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In any case it bothers him very little what Le Roux says. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Interrogative complementive clauses, like interrogative subject clauses, have not been investigated previously in Afrikaans. Our investigation of the Taalkommissiekorpus shows that there are a small number of very dominant patterns, with limited deviation from these patterns. It emerges very clearly from the data that complementive clauses with the general and specific interrogatives are used in very different ways in Afrikaans. General interrogatives are used to suggest uncertainty about the validity of the proposition in the complementive clause. Thus, the most frequent pattern in the data is with the dummy pronoun dit it as subject and the copular verb lyk to seem as main verb, as in example (33). The past tense form het gelyk have.AUX seem.PST seemed is also attested reasonably often, although not nearly as frequently as the present tense form, as in example (34).

| Partykeer lyk dit of dinge ekstra goed gaan sodat jy nie moet sien hoe die teëspoed jou bekruip nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| sometimes seem.PRS it if.COMP things extra well go.PRS so.that you not must.AUX.MOD see.INF how the misfortune you sneak.up.PRS PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sometimes it seems as if things are going extra well, so that you don't see how misfortune sneaks up on you. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit het nie gelyk of iemand juis belang gestel het in die nuus nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it have.AUX not seem.PST if.COMP someone really interest set.PST have.AUX in the news PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It did not seem as if anyone really showed interest in the news. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The verbs voel to feel and voorkom to appear are also found in the data with more than negligible frequencies, also in combination with the dummy pronoun dit it, as illustrated by example (35) and (36). In the case of voorkom, the dominant pattern is the collocation with the modal wil will.

| ... dit voel of daar 'n hoenderbeen in sy keel vassit. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it feel.PRS if.COMP there a chicken bone in his throat tight.sit.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ... it feels as if a chicken bone is stuck in his throat. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit wil voorkom of daar nie plek in rugby is vir ons gekleurde losskakels nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it want.to.AUX.MOD.PRT appear.INF if there not place in rugby be.PRS for our coloured flyhalves PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It would appear as if there isn't room for our coloured flyhalves in rugby. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The pattern extends to the copular verb is be.PRS, which occurs with similar frequency to voel and voorkom in combination with the dummy pronoun dit it, and where the meaning is usually quite similar to lyk or voel, thus not clearly assertive, as illustrated by example (37). The contraction of the pronoun dit and the verb is to dis it=be.PRS it's is quite prominent in the data.

| ... dis of iets in my begin roer van skone verbasing. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it=be.PRS if something in me begin.LINK turn.INF from pure astonishment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ...it's as if something is beginning to move inside me from pure astonishment. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The other major pattern for general interrogatives is a matrix clause with die vraag the question as subject and the copular verb is as main verb, as in example (38), where the meaning of the matrix clause is to assert the actuality of the question being posed.

| Die vraag is dus of 'n mens hierdie nuwe soort "toleransie" kan aanvaar as jy sterk godsdienstige oortuigings het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the question be.PRS thus if a human this new kind tolerance can.AUX.MOD accept.INF if you.SG strong religious convictions have.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The question is therefore if one can accept this new kind of "tolerance" if one has strong religious convictions. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In this case, as with the corresponding matrix clause pattern associated with specific interrogatives, the noun vraag quesion introduces a new twist in the argument, where a particular question is raised as a consequence of the preceding arguments. It serves a cohesive function at textual level, bridging the discussion preceding and following the interrogative complement clause construction use.

As far as specific interrogatives are concerned, there are only two frequent subjects that are used in this construction: the pronoun dit, illustrated by example (39) and (40), and a noun phrase with head noun vraag, illustrated by (41).

| Dit is waar Russiese ruimtevaarders al van die 1960's af opgelei word. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it be.PRS where Russian astronauts already from the 1960s off up.train.PASS be.AUX.PASS.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This is where Russian astronauts have been trained since the 1960s. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dis hoe ek verlede maand se staking opgelos het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it=be.PRS how I last month PTCL.GEN strike up.solve.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This is how I resolved last month's strike. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Die vraag ontstaan watter rol die sonde dan in hierdie verband speel. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the question arise.PRS which role the sin then in this connection play.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The question arises what role sin plays in this regard. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The contracted form dis it's from dit is it is is used in slightly more than 40% of the cases where the subject is the third person impersonal pronoun dit, illustrated by example (40), with the uncontracted form in the remainder of the cases, as illustrated by (39).

The pronoun dit functions not as dummy pronoun, as it does in the case of subject or general interrogative complementive clause constructions, but as anaphor, usually referring back to information in the immediately preceding discourse. Thus, in example (39), the preceding sentence refers to the place where Mark Shuttleworth was trained for his trip into outer space, which is then followed by a further piece of information in the example sentence itself. Likewise, in the case of example (40), taken from a direct quotation in a magazine interview, the pronoun refers back to two statements in the preceding sentences: Ek het nie een van hulle beantwoord nie. Vermy tot elke prys konfrontasie. I did not answer anyone of them. Avoid confrontation at all cost..

The subject noun phrase Die vraag The question in example (41) does not represent an anaphor, but is still a word that ties the proposition in the complementive clause to the surrounding textual context, by drawing attention that all the information presented up to that point raises a question. The complementive clause then explicitly states that question, which serves as transition to the subsequent discussion of that question.

All other subject noun phrases together account for less than 10% of all the data in the sample from the TK, and not a single subject noun phrase amounts to 1% of the data. A number of these low frequency variants are illustrated by the examples in (42), and in general, they function in similar ways to the more prototypical subject noun vraag question.

The verb of the matrix clause in specific interrogative clauses is almost invariantly the verb wees to be (more than 96% of the time in the data set analysed), and specifically the present tense form is is.

- 1979Afrikaanse sintaksis.Van Schaik