- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Compounding is the concatenative word formation process where two or more roots (specifically combination forms), stems, words, and phrases are combined to form a new word. For instance, the word eet+kamer dining room is a compound formed from the nouns eet to eat and tafel table, while morf·o+logie is a compound formed from the roots morf- and -logie, together with the interfix-o-.

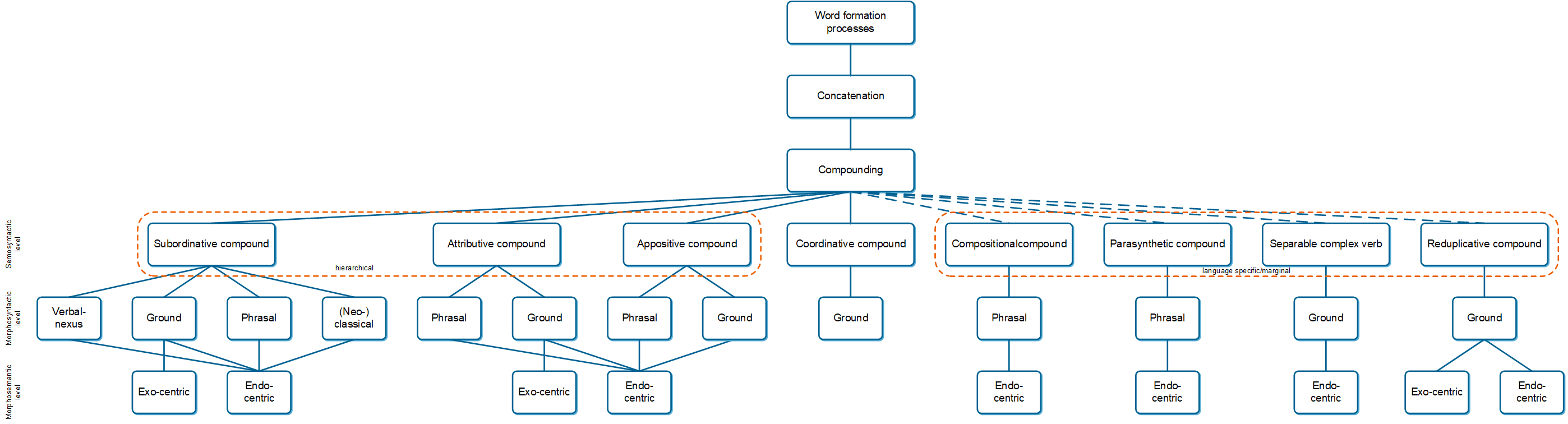

In analyses, a plus sign (+) is used to indicate boundaries between stems/roots in compounds; the middle dot (·) is used before interfixes (and before/after other affixes); the division sign is used for affixoids (÷); an underscore ( _ ) is used for univerbations.Adapting Van Huyssteen and Verhoeven's taxonomy of compounding for Afrikaans and Dutch (2014), which was based on the work of Scalise and Bisetto (2009), the taxonomy in the figure below presents an overview of compounding in Afrikaans. This taxonomy also serves to structure the topics discussed on Taalportaal.

In addition to the classification above, Afrikaans compounds can be classified according to the word class of their heads. The most productive types are nominal compounds and adjectival compounds, while verbal compounds are in principle unproductive. These kinds of compounds are discussed in detail under subordinative compounds.

Scalise and Bisetto's (2009) seminal chapter on the classification of compounds opens with an important observation: "Classification of compounds has been and still is a much-debated issue in the linguistic literature." This is due to issues related to terminology (which is often used and/or applied differently in and for different languages); differences in what is considered to be a compound or not; inconsistent application of (inconsistent) criteria; diverging view-points from different theoretical frameworks (e.g. on the boundaries between morphology and syntax); differences in methodological approaches (e.g. lack of using usage-based data); different purposes (e.g. for computational purposes); etc. One of the most telling examples is the divergent definitions of the term synthetic compound (Von Schroeder 1874; Bloomfield 1933), which is also used synonymously (or near synonymously) with verbal-nexus compound(Marchand 1969), parasynthetic compound, verbal compound(Selkirk 1982), deverbal compound, secondary compound, and syntactic compound. To add to the confusion, terminology and definitions in different languages might also vary, e.g. samestellende samestelling vs. samestellende afleiding in Afrikaans and Dutch (Booij and Van Santen 2017:185-194), or Zusammenbildung in German (see Neef (2015) for a discussion) for the same or related phenomena.

Even though Scalise and Bisetto's (2009) universal taxonomy of compounding is widely accepted, it is still not uniformly adopted in morphological circles. Van Huyssteen and Verhoeven (2014:36) provided an overview of some of the shortcomings and criticism of the Scalise and Bisetto taxonomy, and provided a slightly adapted version of the taxonomy for Afrikaans and Dutch, specifically with the purpose of annotating data for the CompoNet database. Since 2014, new data and theoretical insights necessitated an updated version of Van Huyssteen and Verhoeven's (2014:36) taxonomy, which was published in Van Huyssteen (2017).

The taxonomy used here on Taalportaal is an adaptation of the latter. Where the purpose of the aforementioned taxonomies of Van Huyssteen and Verhoeven (2014), and Van Huyssteen (2017) was for the annotation of data for comparative-linguistic purposes, the purpose here is more of a descriptive-linguistic nature. Also, some of the choices – e.g. to leave outThe most updated version of the taxonomy will always be available here.

- Prototypical properties of compounds

- Prototypical examples: Subordinative compounds

- Prototypical examples: Attributive compounds

- Prototypical examples: Appositive compounds

- Prototypical examples: Coordinative compounds

- Prototypical examples: Compositional compounds

- Prototypical examples: Parasynthetic compounds

- Prototypical examples: Separable complex verbs

- Prototypical examples: Reduplicative compounds

- A note on compounding vs. univerbation

In accordance with the generally accepted properties of (Germanic) compounds (e.g. Kempen (1969:83-135); Lieber and Štekauer (2009); Olsen (2000); Ziering and Van der Plas (2020)), the following properties of prototypical Afrikaans compounds can be mentioned:

- Realisation (form)

- In spoken language, Afrikaans compounds generally have a uniform tempo and stress contour, where the left-hand constituent receives primary stress, and the right-hand constituent secondary stress, following Booij's (1995)compound stress rule (CSR) – see example (1). If the left-hand constituent is a multisyllabic word, it follows the general stress patterns for simplex words (Wissing 2019) – see example (2). In contrast, the head of a phrase normally receives primary stress, or otherwise numerous words in a phrase could carry equal stress – see the examples in (3). 1

swem+bad [ˈsʋɛmˌbɑt] swim+bath swimming pool 2laboratorium+assistent [lɑ.brɑˈto.ri.œm.ɑ.səˌstɛnt] laboratory+assistant laboratory assistant 3Wissing (2019) demonstrated that in compound place names "the final segment appropriates stress", which he ascribed to the fact that "the original constituent segments have lost (or have begun to lose) their original meanings and thus also their status as separate constituents, as part of the more general process of the compound’s gaining, or having gained, monomorphemic status".Contrary to the observations about Dutch by Visch (1989), all categories of Afrikaans compounds (including adjectival and prepositional compounds) have default stress on their first constituent (bar individual exceptions, of course). Compare with the topic on the compound stress rule for Dutch. - In written language, compounds are by default styled as one word, or in some cases with a hyphen (e.g. to avoid legibility problems, or to indicate certain meaning relationships). Orthographical rules have been developed for over more than a century, and which are well-documented in AWS-11. Crucially, AWS-11, 15.1 states that separate words (i.e. in word groups, phrases, and sentences) are written disjunctively, while AWS-11, 15.3 dictates that constituents (i.e. words) in compounds are written conjunctively. 4

film+ekstravaganza (> filmekstravaganza) film extravaganza 5 - The constituents of a compound cannot be separated by other constituents. With reference to example (6b) it is impossible to add another adjective (e.g. *wild·e+swart+bees wild·ATTR+black+bovine), or another noun (e.g. *wild·e+afrikaner+bees wild·ATTR+Africander+bovine) between the two constituents of the compound. In contrast, it is possible to insert other words in phrases, e.g. wild·e, swart bees wild, black bovine, or wild·e afrikaner+bees uncontrollable head of Africander cattle. Excluded from this is swearword infixation, like kind·er-fokken-kak child·LK-fucking-shit balder-fucking-dash (WKJ).

- The constituents of a compound are not interchangeable, unlike words in some phrases. Hypothetically, wild·e, swart bees and swart, wild·e bees would be possible phrases with equal meanings. In contrast, the first two constituents in the compound swart+wild·e+bees white-tailed gnu cannot be interchanged, bar a handful of exceptions.

- In spoken language, Afrikaans compounds generally have a uniform tempo and stress contour, where the left-hand constituent receives primary stress, and the right-hand constituent secondary stress, following Booij's (1995)compound stress rule (CSR) – see example (1). If the left-hand constituent is a multisyllabic word, it follows the general stress patterns for simplex words (Wissing 2019) – see example (2). In contrast, the head of a phrase normally receives primary stress, or otherwise numerous words in a phrase could carry equal stress – see the examples in (3).

- Conceptualisation (meaning)

- The right-hand constituent in a compound mostly functions as both grammatical and semantic head, and is modified by a left-hand constituent (Olsen 2000:908). Such compounds are known as endocentric compounds (a.k.a. determinative compounds, or tatpurusa compounds). Of course, many exceptions abound:

- A few compounds (most often loan words, or loan translations) are left-headed, e.g. ouditeur-generaal auditor-general, who is a kind of and not a kind of , and hence takes plural marking on the left-hand constituent (i.e. ouditeur·s-generaal).

- Exocentric compounds (a.k.a possessive compounds, or bahuvrihi compounds) lack a semantic head, e.g. rooi+kop red+head person with red hair.

- Coordinative compounds (a.k.a. dvandva compounds and/versus kharmadharaya compounds) have a right-hand grammatical head, but two semantic heads, e.g. onderwyser-boer teacher-farmer person who is both a teacher and a farmer, which takes plural marking on the right-hand constituent only (i.e. onderwyser-boer·e). In some definitions (e.g. Bauer 2004) a distinction is made between proper name compounds like Hewlett-Packard as dvandva compounds, and other cases like onderwyser-boer that are considered to be kharmadharaya compounds (or in Bauer's terms also appositional compounds).

- Appositive compounds (a.k.a. appositional compounds) are semantically and grammatically right-headed compounds, but where there are most often an metaphorical interpretation between the left-hand and right-hand constituents (in contrast with attributive compounds that have a literal relation). In appositive compounds the left-hand constituent expresses an attribute (i.e. descriptive quality) of the right-hand constituent by means of a noun or verb (in contrast with attributive compounds where adjectives and adverbs are normally used to express an attribute). (Also see Scalise and Bisetto (2009:51).)

- The left-hand constituent serves as a generic/type, or indefinite specification that restricts or modifies the set of possible denotations of the right-hand constituent. Hence, left-hand constituents are generally bare words or phrases, i.e. words or phrases unmarked for grammatical categories like number, degrees of comparison, case, tense, etc.; see examples in (5). Noticeable exceptions regularly occur in especially phrasal compounds (example (6a)), and attributive compounds (example (6b)). 67extra

If the left-hand constituent is a noun, it is by default (and in principle, for the reasons mentioned above) the unmarked form of the noun (i.e. without plural suffix). The default analysis for a word like perd·e+stal horse stable is therefore [[[perd](N)[e](LK)](allo)[stal](N)](N) (i.e. to analyse the -e- as an interfix, and not as a plural suffix).

Kempen (1969:96) explicitly stated that a plural analysis is only valid if the compound could be contrasted with another compound that is in form and meaning in the singular. Compare the contrastive examples below where it is illustrated that universiteit·e+span could be contrasted with universiteit+span (and a plural interpretation of the e is therefore possible), but since *perd+stal is not an existing word in Afrikaans, the e in perd·e+stal should be analysed as an interfix.

i - The meaning of a compound is not overtly expressed in the combination of the constituents, and are therefore oftentimes semantically ambiguous (or potentially ambiguous). The intended meaning is therefore construed through conventionalised schemas, and encyclopaedic knowledge. Compare the N+N compounds in (7), all with tafel table as right-hand constituent, but with different meaning relations with their left-hand constituents. 8

- Contrary to what is possible in phrases, the left-hand constituent in a compound cannot be modified independently from the right-hand constituent. In a phrase like klein kind small child the adjective can be modified by an adverb like baie very to denote a very small child. In the compound klein+kind grandchild such modification is not possible: both *baie klein+kind and *baie+klein+kind would be ungrammatical, while in baie klein+kind·er·s many small+child·LK·PL many grandchildren the modifier baie is a indefinite numeral, and not an adverb modifying klein.

- The right-hand constituent in a compound mostly functions as both grammatical and semantic head, and is modified by a left-hand constituent (Olsen 2000:908). Such compounds are known as endocentric compounds (a.k.a. determinative compounds, or tatpurusa compounds). Of course, many exceptions abound:

- Usage

- Compounds are typically used as a name of a coherent concept, rather than a description of it. For example, the compound klein+kind child of your son or daughter denotes a category of kinship, while the phrase klein kind small child describes a child in terms of size. Also compare English grandchildchild of your son or daughter, versus grand childvery pleasing child. As Olsen (2000:899) observed: "… compounds often express a more consolidated meaning than an equivalent syntactic phrase."

- Endocentric compounds form the largest and most productive class of compounds. Of these, nominal compounds, and specifically N+N compounds, constitute the largest subclass (i.e., circa 80% of all Afrikaans compounds are N+N compounds).

The definition of what a compound is, is at the heart of some of the controversies around the definitions of the concepts word and phrase, and subsequently around the boundaries between morphology and syntax. Literature about the topic abound (see Ziering and Van der Plas (2020) for a recent overview), with opposing theoretical viewpoints being defended quite strongly.

In a seminal article, Haspelmath (2011) examined ten criteria for defining a cross-linguistically valid concept of "(morphosyntactic) word", viz.: potential pauses; free occurrence; mobility; uninterruptibility; non-selectivity; non-coordinatability; anaphoric islandhood; nonextractability; morphophonological idiosyncrasies; and deviations from biuniqueness. He showed that "none of them is necessary and sufficient on its own, and no combination of them gives a definition of "word" that accords with linguists' orthographic practice." He concluded that "we do not currently have a good basis for dividing the domain of morphosyntax into "morphology" and "syntax", and that linguists should be very careful with general claims that make crucial reference to a cross-linguistic "word" notion." This viewpoint is fully compatible with a constructionist definition of grammar, where there is no difference between morphology and syntax, bar the "size" of the constructions being described.

| Morphosyntactic type | Morphosemantic type | POS of constituent 1 | POS of constituent 2 | POS of compound | Example | Gloss | Translation |

| Verbal-nexus | Endocentric | N | V·ADJZ | ADJ | hand+vervaardig·de | hand+produce·ADJZ | hand-made |

| N | V·NMLZ | N | gras+sny·er | grass+cut·NMLZ | lawn mower | ||

| V | V·NMLZ | N | eet+staak·ing > eetstaking | eat+strike·NMLZ | hunger strike | ||

| ADJ | V·NMLZ | N | kaal+nael·er | naked+run·NMLZ | streaker | ||

| ADV | V·PTCP | ADJ | dig+bebos·te | thick+afforest·ADJZ | thickly wooded | ||

| Ground | Endocentric | N | N | N | tafel+poot | table+leg | table leg |

| N | ADJ | ADJ | kleur+blind | colour+blind | colour blind | ||

| N | ADV (POSTP) | ADJ/ADV | pad+langs | road+along | via road; directly | ||

| N | V | N | dag+breek | day+break | dusk | ||

| N | V | V | raad+pleeg | advice+commit | to consult | ||

| NUM | N | N | twee+klank | two+sound | diphthong | ||

| V | N | N | stryk+plank | iron+board | ironing board | ||

| V | ADJ | ADJ | werk+sku | work+shy | lazy | ||

| ADJ | N | N | siek+bed | sick+bed | sickbed | ||

| INTERJ | N | N | sjoe+broek | ouch+pants | hot pants | ||

| Exocentric | V | N | V | knip+oog | snip+eye | to wink | |

| V | N | N | suip+lap | booze+cloth | drunkard | ||

| V | N | ADV | druip+stert | drip+tail | embarrassed | ||

| V | ADV | N | trap+suutjies | tread+softly | chameleon | ||

| N | N | N | tronk+voël | jail+bird | jailbird | ||

| N | N | ADJ | hoender+kop | chicken+head | drunk | ||

| ADV | V | N | mal+trap | crazy+step | crazy, jolly person | ||

| Phrasal | Endocentric | VP | N | N | skop-skiet-en-donder-film | kick-shoot-and-hit-movie | action movie |

| NP | N | N | kaas-en-wyn-onthaal | cheese-and-wine-party | cheese and wine party | ||

| sentence | N | N | God-is-dood-teologie | God-is-dead-theology | "God is dead" theology | ||

| (Neo)classical | Endocentric | root | root | N | hidro+logie | hydro+logy | hydrology |

| root | N | N | bio+brandstof | bio+fuel | biofuel | ||

| N | root | N | Japan+logie > Japannologie | Japan+logy | Japanese studies |

| Morphosyntactic type | Morphosemantic type | POS of constituent 1 | POS of constituent 2 | POS of compound | Example | Gloss | Translation |

| Ground | Endocentric | ADJ | N | N | blou+draad | blue+wire | galvanised wire |

| ADJ (PREP.INTR) | N | N | buite+kamer | outside+room | outside room | ||

| ADV | N | N | terug+weg | back+way | the way back | ||

| ADV | ADJ | ADJ | donker+blond | dark+blonde | dark blonde | ||

| N | ADJ (PREP.INTR) | ADJ | bek+af | beak+off | disappointed | ||

| Exocentric | ADJ | N | N | rooi+kop | red+head | person with red hair | |

| ADJ | N | ADJ | kaal+voet | bare+foot | barefooted | ||

| ADJ | N | ADV | vroeg+dag | early+day | early in the morning | ||

| NUM | N | N | tien+kamp | ten+camp | decathlon | ||

| Phrasal | Endocentric | AP | N | N | los-en-vas-praatjies | loose-and-set-talks | random chatting |

| NP | N | N | kop-aan-kop-botsing | head-on-head-collision | head-on collision | ||

| PP | N | N | in-die-kol-humor | in-the-spot-humour | spot-on humour |

| Morphosyntactic type | Morphosemantic type | POS of constituent 1 | POS of constituent 2 | POS of compound | Example | Gloss | Translation |

| Ground | Endocentric | N | N | N | treffer+liedjie | hit+song | hit song |

| N | ADJ | ADJ | hond+mak | dog+tame | as tame as a dog | ||

| N | ADJ | ADJ | hond+lelik | dog+ugly | very ugly | ||

| V | ADJ | ADJ | spring+lewendig | jump+lively | alive and well | ||

| Phrasal | Endocentric | VP | ADJ | ADJ | kielie-my-maag-lekker | tickle-my-stomach-nice | as nice as tickling my stomach |

| NP | ADJ | ADJ | sonsak-in-Ibiza-mooi | sunset-in-Ibiza-pretty | sunset-in-Ibiza-pretty |

| Morphosyntactic type | Morphosemantic type | POS of constituent 1 | POS of constituent 2 | POS of compound | Example | Gloss | Translation |

| Ground | Endocentric | N | N | N | skrywer-boer | writer-farmer | writer-farmer |

| ADJ | ADJ | ADJ | stom+verbaas | mute+surprised | very surprised | ||

| V | V | V | sit-lê | sit-lie | sit and lie | ||

| PREP | PREP | PREP | van+af | from+of | from | ||

| PREP | PREP | ADV (PREP.INTR) | voor+op | before+above | firstly | ||

| Exocentric | PR | PR | PR | Bosnië-Herzegowina | Bosnia-Herzegovina | Bosnia-Herzegovina | |

| N | N | N | ma-kind | mother-child | mother-child |

| Morphosyntactic type | Morphosemantic type | POS of constituent 1 | POS of constituent 2 | POS of compound | Example | Gloss | Translation |

| Phrasal | Endocentric | NP | N | N | groot+skerm+televisie | big+screen+television | big screen television |

| NP | N | N | twee+sitplek+motor | two+seat+car | two-seater | ||

| PP | N | N | buite+boord+motor | out+board+motor | outboard motor | ||

| AP | N | N | ou+jong+kêrel | old+young+dude | bachelor | ||

| VP | N | N | lekker+sit+stoel | nicely+sit+chair | comfortable chair | ||

| VP | N | N | haar+sny+skêr | hair+cut+scissors | hairdressing scissors |

| Morphosyntactic type | Morphosemantic type | POS of constituent 1 | POS of constituent 2 | POS of compound | Example | Gloss | Translation |

| Phrasal | Endocentric | NP | NMLZ | N | groot+skaal·s | large+scale·ADJZ | large-scale |

| NP | ADJZ | ADJ | een+blaar·ig > eenblarig | one+leaf·ADJZ | monopetalous | ||

| VP | NMLZ | N | alleen+loop·er > alleenloper | alone+walk·NMLZ | loner | ||

| VP | NMLZ | N | ter+aarde+bestel·ing > teraardebestelling | to+earth+deliver·NMLZ | burial |

| Morphosyntactic type | Morphosemantic type | POS of constituent 1 | POS of constituent 2 | POS of compound | Example | Gloss | Translation |

| Ground | Endocentric | PREP | V | V | in+gooi | in+throw | to throw in |

| ADJ | V | V | goed+keur | good+grade | to approve | ||

| ADV | V | V | neer+gooi | down+throw | to throw down | ||

| N | V | V | vleis+braai | meat+roast | to barbeque | ||

| Exocentric | ADV (PREP.INTR) | ADJ | V | aan+dik | on+thick | to exaggerate | |

| ADV (PREP.INTR) | N | V | in+perk | in+bound | to confine; to limit |

| Morphosyntactic type | Morphosemantic type | POS of constituent 1 | POS of constituent 2 | POS of compound | Example | Gloss | Translation |

| Ground | Endocentric | V | V | V | vat-vat | touch-touch | to touch tentatively |

| ADJ | ADJ | ADJ | lang-lang | long-long | very long | ||

| ADV | ADV | ADV | nou-nou | now-now | just now | ||

| N·PL | N.PL | N·PL | bakk·e-bakk·e | bowl·PL-bowl·PL | many/countless bowls | ||

| NUM | NUM | ADV | twee-twee | two-two | in pairs of two | ||

| Exocentric | INTERJ | INTERJ | N | hoep-hoep | hoop-hoop | Upupa africana (name of a common South African garden bird) | |

| INTERJ | INTERJ | ADV | doef-doef | boom-boom | pit-a-pat | ||

| INTERJ | INTERJ | V | tjirp-tjirp | chirp-chirp | to chirp iteratively | ||

| N | N | N | huis-huis | house-house | playing house | ||

| V | V | ADV | lag-lag | laugh-laugh | easily | ||

| N | N | ADV | plek-plek | place-place | sporadically |

Compound words of non-lexical categories, such as conjunctions, have not been formed through compounding, but through univerbation. This is the case for conjunctions like omdat because and deurdat because, and complex prepositions such as agterop at/on the back, behind. For a discussion of cases like these, see the topic on univerbation.

- 2004A Glossary of MorphologyEdinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

- 1995The phonology of DutchOxfordOxford University Press

- 2017Morfologie. De woordstructuur van het Nederlands.AmsterdamAmsterdam University Press

- 2020Syntax of Dutch: Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 2019Hoe een hele bijzin een voorzetsel kan worden.Trouw6 septembern.p.

- z.j.Dikke Van Dale online

- z.j.Dikke Van Dale online

- z.j.Dikke Van Dale online

- 1992Van Dale: Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal: 3 Dl.Van Dale Lexicografie

- 2010Met (het) oog op morgen: Opstellen over taal, taalverandering en standaardtaalUniversitaire Pers Leuven

- 2014Over complexe preposities en convergentiePatroon en argument. Een dubbelfeestbundel bij het emeritaat van William Van Belle en Joop van der HorstUniversitaire Pers Leuven

- 1969Samestelling, afleiding en woordsoortelike meerfunksionaliteit in Afrikaans.Nasou

- 1969Samestelling, afleiding en woordsoortelike meerfunksionaliteit in Afrikaans.Nasou

- 1969The categories and types of present-day English word formationMünchenBeck

- 2009The Oxford Handbook of CompoundingLieber, R. & Štekauer, P. (eds.)The classification of compoundsOxford: Oxford University Press34–53

- 2009The Oxford Handbook of CompoundingLieber, R. & Štekauer, P. (eds.)The classification of compoundsOxford: Oxford University Press34–53

- 2009The Oxford Handbook of CompoundingLieber, R. & Štekauer, P. (eds.)The classification of compoundsOxford: Oxford University Press34–53

- 2009The Oxford Handbook of CompoundingLieber, R. & Štekauer, P. (eds.)The classification of compoundsOxford: Oxford University Press34–53

- 2017Morfologie.(In Carstens, W.A.M. & Bosman, N.., reds. Kontemporêre Afrikaanse taalkunde. Pretoria : Van Schaik. 2de uitg., p. 177-214.)Van Schaik

- 2017Morfologie.(In Carstens, W.A.M. & Bosman, N.., reds. Kontemporêre Afrikaanse taalkunde. Pretoria : Van Schaik. 2de uitg., p. 177-214.)Van Schaik

- 2014A taxonomy for Afrikaans and Dutch compounds.(In: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2104) The first workshop on Computational Approaches to Compond Analysis (ComAComA) Dublin <ireland. pp. 31-40.)

- 2014A taxonomy for Afrikaans and Dutch compounds.(In: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2104) The first workshop on Computational Approaches to Compond Analysis (ComAComA) Dublin <ireland. pp. 31-40.)

- 2014A taxonomy for Afrikaans and Dutch compounds.(In: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2104) The first workshop on Computational Approaches to Compond Analysis (ComAComA) Dublin <ireland. pp. 31-40.)

- 2014A taxonomy for Afrikaans and Dutch compounds.(In: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2104) The first workshop on Computational Approaches to Compond Analysis (ComAComA) Dublin <ireland. pp. 31-40.)

- 2014A taxonomy for Afrikaans and Dutch compounds.(In: Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2104) The first workshop on Computational Approaches to Compond Analysis (ComAComA) Dublin <ireland. pp. 31-40.)

- 1989The rhythm rule in English and DutchUtrecht UniversityThesis

- 2007Dislocation and backgroundingLinguistics in the Netherlands24235-247

- 2007Dislocation and backgroundingLinguistics in the Netherlands24235-247

- 2019Herbesoek aan Afrikaanse klemtoon: Is dit (nog) ’n inisiëleklemtoontaal?

- 2019Herbesoek aan Afrikaanse klemtoon: Is dit (nog) ’n inisiëleklemtoontaal?