- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

The acoustic properties of stress provide perceptual cues for recognizing stress. There are four important perceptual correlates:

- duration,

- intensity,

- vowel quality and

- fundamental frequency.

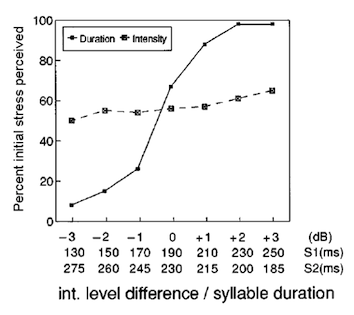

Figure 1 shows the main results of a perception study for Dutch modelled after Fry (1955). In the experiment the durations of V1 and V2 in each of five minimal stress pairs (object, subject, digest, compact, import) were varied in seven steps between (and including) values found (averaged over ten speakers) in natural tokens with initial and with final stress. These seven duration steps were combined with seven intensity differences (by amplifying V1 and at the same time attenuating V2) such that the V1–V2 difference varied between +3 and –3 dB. A single Dutch minimal stress pair, the reiterant non-word nana was presented in a sentence frame wil je [target] ZEGgen will you [target] SAY with the sentence stress on the final verb; these variations were suggestive of word stress only – the range of intensity differences in the Dutch stimuli was much smaller (but reflected actual speech production) than in Fry's materials with sentence stress on the targets. Listeners indicated whether they perceived a noun (initial stress) or a verb (final stress). Figure 1 presents the perceived initial stress for duration steps in percent (averaged over words and intensity steps) and for intensity steps (averaged over words and duration ratios).

(After Sluijter, Van Heuven & Pacilly 1997)

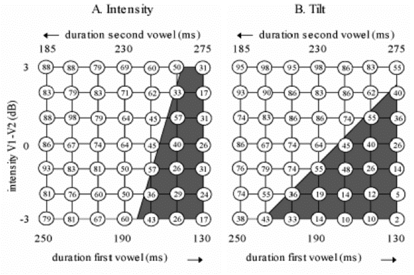

The following figure 2 is a quasi-3D plot of percent initial stress perceived as a function of the difference in vowel duration (X-axis) and of the difference in intensity (Y-axis). The boundary in the figure separates the white area with a majority of initial stress decisions from the dark area with a majority of final stress responses.

(After Van Heuven and Sluijter 1996)

In panel A the boundary runs at an angle that is much steeper than 45°, which indicates that the duration parameter outweighs the intensity parameter as a stress cue. It also shows that intensity variations are largely inconsequential: they cannot swing the majority decision from initial to final stress for six out of seven duration steps; only when V1 = 170 ms and V2 = 245 ms does intensity yield a (shallow) cross-over from 43 to 60% initial-stress responses.

Sluijter et al. (1997) also included a set of stimuli in which the same intensity differences were generated on V1 and V2 but in such a way that no differences were made at frequencies below 500 Hz and all the changes were concentrated at frequencies above 500 Hz, thereby creating a change in spectral slope. Panel B in figure 2 above shows that (selective) intensity differences (affecting spectral tilt) are as strong a stress cue as are the duration differences: the boundary now runs at a 45° angle. In this experiment, the stimuli had been presented over headphones with artificial reverberation added. The reverb (realistic of room acoustics) obscures temporal details. When the same materials were presented over headphones without reverb, the effects of selective intensity were smaller than those of duration but still larger than those of uniform intensity differences.

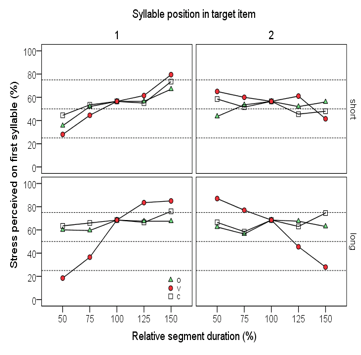

Duration generally outweighs other cues for word stress. What are the effects of the duration of subsyllabic units such as the onset consonant, the vocalic nucleus and the coda consonant? An experiment that addresses this issue was reported in Van Heuven (2014). In reiterant stimuli, with B-class vowels (short vowels) ( /pAfpAf, tAstAs/), and with A-class vowels (long vowels) ( /pafpaf, tastas/) the durations of onset, nucleus and coda were varied separately in steps of 50, 75, 100, 125 and 150 percent of the original duration. The stimuli were synthesized from diphones which had been excerpted from stressed syllables produced in nonsense words with sentence stress, so that all original segments were equally suggestive of (strong) stress. Results were as in figure 3.

Figure 4 shows that, overall, effects of changing the duration of the vocalic nucleus are large but changes in consonant durations, whether in the onset or in the coda, have little or no effect on stress perception. A complete cross-over from stress perceived on the first syllable (S1) to stress perceived on the second syllable (S2) is found for vowel duration change, except when the vowel is short (B-class) and in the final syllable of the target non-word (top-right panel). Moreover, the effect of changing the (vowel) duration is weaker overall when the changes are implemented in S2 than in S1. Changing the duration of a consonant only affects stress perception if the change takes place in an S1 with a short (B-class) vowel (top-left panel) but even then the effect is still somewhat smaller for consonants than for the vowel. In this condition, it does not matter whether the consonant is in the onset or in the coda. So, it seems safe to conclude that the older literature was right in assuming that vowel duration by itself, rather than syllable duration or rhyme duration, is the relevant duration cue.

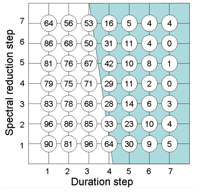

A direct comparison of vowel duration and quality was made for Dutch (Van Heuven and De Jonge 2011). They varied the V1/V2 ratio and the quality of V1 in the Dutch stress pair canon ~ kanon (see above) in seven steps along each continuum. Targets were presented in postfocal position (no F0 movement on the target) in a carrier ik heb gisteren een canon/kanon gehoord [ɪk hɛp ˈxɪstərə(n) ən ˈkanɔn/kaˈnɔn xəˈhort] I have yesterday a canon/cannon heard I heard a canon/cannon yesterday. The results are shown in figure 4, in quasi-3D format. Convincing cross-overs are obtained for the duration steps. Just one, very incomplete, change from perceived initial stress to final stress is obtained by changing vowel quality from clear to fully reduced to schwa; this change is obtained only when the duration cue is ambiguous (step 4). Fry's (1965) conclusion for English is confirmed here for Dutch: vowel reduction is a much weaker stress cue than vowel duration.

(From Van Heuven and De Jonge 2011)

In natural human speech the F0 change has to exceed a certain threshold in order to function as a stress cue, and if it does it typically imparts sentence stress on the word that carries the F0 change. Since sentence stress outranks word stress, this makes the F0 change the strongest stress cue of all. Fry (1958) was among the first to study the effect of F0 change on stress perception, comparing its strength with that of varying the duration ratio of V1 and V2 in the English noun-verb pair subject. The duration ratio was varied as in Fry (1955). In one experiment, Fry synthesized the syllable sub- on a flat 97 Hz followed by stepwise F0 rise to -ject of 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 60 and 90 Hz. This set of eight rises was supplemented with a similar set of eight falls, with the level higher F0 on sub- and the low 97 Hz pitch on -ject. The total set of 5 (V1/V2 ratios) × 8 (step sizes) × 2 (directions) = 80 stimuli. The results bear out that the frequency step-up generated perceived stress on the second syllable (between 61 and 75% for the various F0 changes but averaged over duration ratios) whilst a step down yielded stress on the first syllable (between 48 and 80%), i.e. the higher-pitched syllable is heard as stressed. The absolute size of the step, however, did not matter: a 5-Hz change was as influential as a 90-Hz change. On average, however, the effect of changing F0 turned out to be smaller than that of varying the duration ratio.

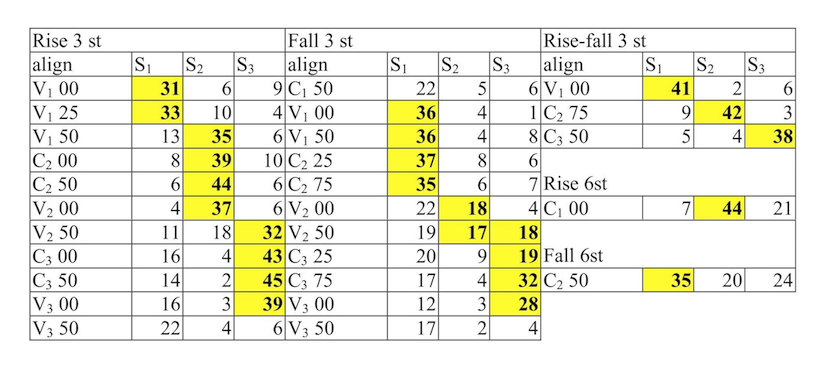

Van Katwijk (1974: 76-88) varied F0 movements in a Dutch reiterant nonsense item /s{s{s{s/ in a rather more realistic fashion. F0 changes were implemented relative to a fixed declination of 5 st/s. Keeping all other parameters constant, F0 rises and falls of 3-st during 100 ms were generated at eleven different time points. The table under 5specifies the alignment for the onset of the F0 movement with respect to the duration of a segment. Here ‘V1 00’ means that the F0 movement begins at 0% of the duration of the first vowel, i.e. at the vowel onset. Van Katwijk also generated three stimuli with rise-fall contours, and two (one rise, one fall) with 6-st excursion sizes (during 200 ms).

(After Van Katwijk 1974: 81-83)

The results show that the location of the F0 movement greatly influences the perception of stress. A simple rise or rise+fall at the beginning of a syllable suffices to attract a clear majority of stress responses to that syllable (indicated by yellow shading in the table under 5). Simple falls tend to attract fewer stress judgments than rises do, especially when they are associated with the medial or final syllable. For a simple F0 fall to impart stress on a syllable it has to be aligned rather late in the syllable or even in the beginning of the next syllable. The complex rise-fall does not attract more stress judgments than a simple rise; long 6-st rises and falls do not attract more stress judgments than 3-st exemplars. There were also stimuli with differences in vowel duration and intensity but never in combination with F0, or with each other, so that no direct comparison of cue strengths is possible.

Fry (for English) as well as Van Katwijk (for Dutch) insist that F0 change is a stronger stress cue than duration. This claim remains rather unsubstantiated, however, either because the experiment does not allow the conclusion to be drawn, or because the crucial data were not presented. Although Fry (1958) provides at least circumstantial evidence, it is not the case that an F0 change can never be overridden by temporal cues in his materials.

- 1955Duration and Intensity as physical correlates of linguistic stressJournal of the Acoustical Society of America27765-768

- 1955Duration and Intensity as physical correlates of linguistic stressJournal of the Acoustical Society of America27765-768

- 1958Experiments in the perception of stressLanguage and Speech1126-152

- 1958Experiments in the perception of stressLanguage and Speech1126-152

- 1965The dependence of stress judgments on vowel formant structureZwirner, E. & Bethge, W. (eds.)Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of Phonetic SciencesBasel306-311

- 2014Stress and segment duration in DutchWhere the principles fail. A festschrift for Wim Zonneveld on the occasion of his 64th birthdayUtrechtUtrecht Institute of Linguistics OTS217-228

- 2011Spectral and temporal reduction as stress cues in DutchPhonetica68120-132

- 2011Spectral and temporal reduction as stress cues in DutchPhonetica68120-132

- 1996Notes on the phonetics of word prosodyStress patterns of the worldHIL Publications 2Part 1: BackgroundThe HagueHolland Academic Graphics233-269

- 1974Accentuation in Dutch: An experimental linguistic studyAmsterdamVan Gorcum

- 1974Accentuation in Dutch: An experimental linguistic studyAmsterdamVan Gorcum

- 1974Accentuation in Dutch: An experimental linguistic studyAmsterdamVan Gorcum

- 1997Spectral balance as a cue in the perception of linguistic stressJournal of the Acoustical Society of America101503-513

- 1997Spectral balance as a cue in the perception of linguistic stressJournal of the Acoustical Society of America101503-513