- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

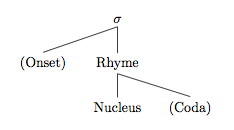

The rhyme is an obligatory syllableconstituent, which can optionally branch into a nucleus and a coda. The nucleus is obligatory; the coda is optional.

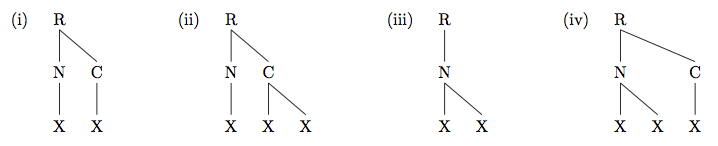

According to Booij (1995:26) and Trommelen (1984), a rhyme in Dutch consists of at least two and maximally three positions. The rhyme structures in figure 2 (i-iv) are attested in Dutch as illustrated by the examples in (1). The diphthongs in examples (1d) and (1f) pattern with the A-class vowels in examples (1c) and (1e). Notice that the representations in example (2) are not allowed in Dutch (see also figure 3 (v-vii)).

However, a few exceptional cases to the fact stated in (2c) can be found in Dutch. In words like twaalf /tʋalf/ [tʋalf] twelve or Weesp /ʋesp/ [ʋesp] place name, an A-class vowel precedes a consonant cluster of non-coronals, resulting in a sequence of four rhyme positions. The same holds for the past tense forms of some strong verbs, e.g. hielp /hilp/ [hilp] help.SG.PST helped or stierf /stirf/ [stirf] die.SG.PST died, and a few words ending in /-rn/, e.g. hoorn /horn/ [hor(ə)n] horn or lantaarn /lɑntarn/ [lɑnˈtar(ə)n] streetlamp (all examples in this paragraph are taken from Booij (1995: 26, footnote 8) who also mentions that -rn clusters tend to be reduced with the help of schwa epenthesis).

Words like herfst /hɛrfst/ [hɛrfst] autumn, fall or promptst [prɔmptst] [prɔmp(t)st] most prompt seem to be additional counterexamples to the fact stated in (2b). However, it can be observed that Dutch generally allows for extra-long consonant sequences at the end of prosodic words ('edge of constituent phenomena', see Moulton 1956, Booij 1983). In addition to the maximally three positions of the rhyme, Dutch allows for three additional prosodic word-final appendix positions, which can only be filled by coronals (cf. coda).

Whereas the type of coda consonants in structures like in (1e) is unrestricted in word-final position, Trommelen (1984:121) observes that some restrictions apply in word-medial coda positions (cf. also phonotactics at the word level). The examples in table (1) illustrate that on the face of it A-class vowels can solely be followed by obstruents (column 1) in word-medial coda position. Column 3 provides evidence that sonorants are not generally excluded as word-medial coda consonants.

| bauksiet /bɑuk.sit/ bauxite | teempo /tem.po/ | tempo /tɛm.po/ tempo |

| hypnose /hip.no.sə/ hypnosis | oomnibus /om.ni.bʏs/ | omnibus /ɔm.ni.bʏs/ bus |

| vreugde /vrøɣ.də/ joy | peerzik /per.zɪk/ | perzik /pɛr.zɪk/ peach |

| klooster /klos.tər/ convent | oorkest /or.kɛst/ | orkest /ɔr.kɛst/ orchestra |

The description given above stating that rhymes in Dutch consist of minimally two and maximally three positions relies crucially on the assumption that Dutch distinguishes quantitatively short and long vowels, i.e. vowels that either occupy one or two nuclear positions (X-slots, x-positions; cf. Moulton 1962, Zonneveld 1978, Trommelen 1984, Van der Hulst 1984, Booij 1995, Kooij and Van Oostendorp 2003). B-class vowels count as monopositional; A-class vowels count as bipositional in accordance with diphthongs. Although the length distinction approach is able to capture the differing behaviour of the two classes of vowels with respect to syllable structure (see examples (1) and (2)) and stress assignment, the approach has to face some shortcomings.

Van Oostendorp (1995; 2000) discusses seven problematic issues that arise from following a length-contrast approach in vowels. First, it is problematic that in a quantity based account the high A-class vowels /i, y, u/ pattern with the short vowels, i.e. B-class vowels, in their phonetic length even though they pattern with the non-high long vowels /e, o, ø, a/ phonologically. (Gussenhoven (2009) observes that "[u]nlike what appears to be generally assumed, the long tense vowels of Dutch are only longer than short vowels in stressed syllables, i.e., in the head of the foot".) Furthermore, a vowel-quantity based account must stipulate that schwa is a phonologically long vowel, although phonetically short, since it does occur in open syllables word-finally (cf. stage /sta.ʒə/ internship) and cannot precede branching codas consisting of non-coronals (arend /arənd/ eagle but /*arəmp/; cf. Botma & Van Oostendorp 2012). Second, Van Oostendorp points out that a vowel-quantity based account has problematic consequences from a typological point of view, too. It implies that Dutch possesses the syllable types CVC and CVV (possibly also CVCC and CVVC) but lacks the CV type - making Dutch a typologically highly marked language. Moreover, following this approach, Dutch seems to be a weight-sensitive language in which only closed CVC syllables and CVV syllables containing diphthongs count as heavy whereas CVV syllables containing A-class vowels or schwa count as light or even as superlight. The fourth problematic issue is related to the distribution of A-class vowels and B-class vowels in the Dutch vowel inventory. Trubetzkoy (1939) observed that, given a natural class of segments that gets decomposed into two disjoint subsets based on some phonological property, the larger subset is normally the unmarked one. This assumption runs counter to the fact that the larger set of bipositional A-class vowels is structurally more complex and should therefore be presumed to be more marked than the monopositional B-class vowels. Another problematic issue is the fact that certain morpheme structure constraints seem to make reference to a difference in quality of the vowels rather than their quantity. Sequences like /jɪ-/ and /ʋʏ-/ are acceptable in Dutch, whereas /*ji-/, /*ʋy-/ and /*ʋø-/ are not. This difference is hard to capture with a vowel-quantity based approach since the corresponding vowels would differ exclusively in the number of occupied positions, i.e. their phonological quality is identical. As the sixth issue, Van Oostendorp claims that secret languages and language games treat A-class vowels as units and, crucially, as identical to B-class vowels although a difference can usually be found in other languages (see references in Van Oostendorp 1995; 2000). Lastly, Van Oostendorp mentions cross-dialectal evidence from Dutch varieties that provide vowels differing in quantity and quality. He proposes that the contrast in quality might be underlying and that the difference in quantity is "invoke[d by] a special mechanism" that is active in Dutch anyway and has received phonological status in these particular dialectal areas.

The alternative approach mentioned in the last paragraph assumes that a contrast in tenseness is underlyingly active to differentiate between the two types of Dutch vowels (cf. Cohen 1959, De Rijk 1967, Smith et al. 1989, Hermans 1992, Van Oostendorp 1995, 2000, Gussenhoven 2009). All the other properties, i.e. the distribution of occurrence in open vs. closed syllables or phonetic length, are derived from the difference in tenseness. Smith et al. (1989) understand tenseness as equivalent to ATR (advanced tongue root) or rather its phonetic correspondent of pharyngeal expansion. They specify tense vowels, i.e. A-class vowels, with a dependent [I] element in contrast to lax vowels, i.e. B-class vowels, which lack this specification. Schwa is not specified for any phonological feature, which leaves unaccounted for that schwa patterns distributionally with tense vowels in open and closed syllables. Motivated by this last fact, Van Oostendorp (1995, 2000) alternatively proposes that B-class vowels should be specified by the monovalent feature [lax] (or [-ATR]) instead. The lax specification not only captures the similarities between A-class vowels and schwa, it also leaves the larger set of A-class vowels less complex compared to the smaller set of B-class vowels. To cover the fact that lax vowels exclusively occur in closed syllables, Van Oostendorp introduced the projection constraint Connect(N, [lax]), which is, roughly, defined as:

A third approach assumes that the phonological distinction of A-class vowels and B-class vowels holds at the prosodic level, i.e. allowing for a branching or non-branching rhyme structure. All other phonetic properties, i.e. differences in length and tenseness, are a direct result of underlying syllable structure and subsequent stress assignment (cf. Botma and Van Oostendorp 2012). The underlying idea can already be found in the work of pre-/early structuralists - the contrast of 'strongly cut' and 'weakly cut' vowels (cf. the concept of syllable cut/Silbenschnitt in Sievers 1901; Trubetzkoy 1939;Botma and van Oostendorp 2012; cf. also Vennemann 1991 for a similar phenomenon in German).

- 1983Principles and parameters in prosodic phonologyLinguistics21249-80

- 1995The phonology of DutchOxfordOxford University Press

- 1995The phonology of DutchOxfordOxford University Press

- 1995The phonology of DutchOxfordOxford University Press

- 1995The phonology of DutchOxfordOxford University Press

- 2012A propos of the Dutch vowel system 21 years on, 22 years onPhonological Explorations: Empirical, Theoretical and Diachronic IssuesBerlinMouton de Gruyter

- 2012A propos of the Dutch vowel system 21 years on, 22 years onPhonological Explorations: Empirical, Theoretical and Diachronic IssuesBerlinMouton de Gruyter

- 2012A propos of the Dutch vowel system 21 years on, 22 years onPhonological Explorations: Empirical, Theoretical and Diachronic IssuesBerlinMouton de Gruyter

- 2012A propos of the Dutch vowel system 21 years on, 22 years onPhonological Explorations: Empirical, Theoretical and Diachronic IssuesBerlinMouton de Gruyter

- 1959Fonologie van het Nederlands en het Fries: Inleiding tot de moderne klankleerMartinus Nijhoff

- 2009Vowel duration, syllable quantity and stress in DutchThe nature of the word. Essays in honor of Paul KiparskyCambridge, MA.; LondonMIT Press181--198

- 2009Vowel duration, syllable quantity and stress in DutchThe nature of the word. Essays in honor of Paul KiparskyCambridge, MA.; LondonMIT Press181--198

- 1992On the representation of quasi-long vowels in Dutch and LimburgianBok-Bennema, R. & Hout, R. van (eds.)Linguistics in the NetherlandsAmsterdam

- 1984Syllable structure and stress in DutchDordrechtForis

- 2003Fonologie. Uitnodiging tot de klankleer van het NederlandsAmsterdamAmsterdam University Press

- 1956Syllable nuclei and final consonant clusters in GermanFor Roman Jakobson: Essays on the occasion of his sixtieth birthdayMouton

- 1962The vowels of Dutch: phonetic and distributional classesLingua11294-312

- 1995Vowel Quality and Phonological ProjectionTilburg UniversityThesis

- 1995Vowel Quality and Phonological ProjectionTilburg UniversityThesis

- 1995Vowel Quality and Phonological ProjectionTilburg UniversityThesis

- 1995Vowel Quality and Phonological ProjectionTilburg UniversityThesis

- 1995Vowel Quality and Phonological ProjectionTilburg UniversityThesis

- 2000Phonological ProjectionNiemeyer

- 2000Phonological ProjectionNiemeyer

- 2000Phonological ProjectionNiemeyer

- 2000Phonological ProjectionNiemeyer

- 2000Phonological ProjectionNiemeyer

- 1967Apropos of the Dutch vowel systemMIT

- 1901Grundzüge der PhonetikWiesbadenBreitkopf und Kärtel

- 1989Apropos of the Dutch vowel system 21 years onLinguistics in the Netherlands 1989DordrechtForis133--142

- 1989Apropos of the Dutch vowel system 21 years onLinguistics in the Netherlands 1989DordrechtForis133--142

- 1989Apropos of the Dutch vowel system 21 years onLinguistics in the Netherlands 1989DordrechtForis133--142

- 1984The Syllable in DutchDordrechtForis

- 1984The Syllable in DutchDordrechtForis

- 1984The Syllable in DutchDordrechtForis

- 1984The Syllable in DutchDordrechtForis

- 1939Grundzüge der PhonologiePragueJednota českých matematiků a fysiků

- 1939Grundzüge der PhonologiePragueJednota českých matematiků a fysiků

- 1991Syllable structure and syllable cut prosodies in Modern Standard GermanBertinetto, Pier Marco, Kenstowicz, Michael & Loporcaro, Michele (eds.)Certamen Phonologicum II. Papers from the 1990 Cortona Phonology MeetingTurin211-243

- 1978A formal theory of exceptions in generative phonologyDordrechtForis