- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Frisian has many nouns ending in schwa, which have a schwa-less allomorph, used mainly in particular morphological contexts. Schwa-final nouns have the definite article de (not it). This might lead one to assume that noun-final schwa has the status of a suffix, which is argued not to be the case.

Frisian has many nouns ending in schwa, examples of which are given in (1):

| Examples of nouns ending in schwa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | seage | /sɪəɣə/ | saw | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | planke | /plaŋkə/ | board; shelf | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. | skjirre | /skjɪrə/ | scissors | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| d. | harke | /harkə/ | rake | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| e. | doaze | /doəzə/ | box | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| f. | tomme | /tomə/ | thumb | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In Dutch, only a small number of nouns with final schwa have remained. The Dutch counterparts of the words in (1) are (a) zaag, (b) plank, (c) schaar, (d) hark, (e) doos, and (f) duim, so without final schwa.

Noun-final schwa has a special status, in that it determines the word class and the sub-word class of the free morphemes it is part of. Firstly, a simplex content word ending in schwa is a noun.

There are no more than a handful of exceptions to this regularity:

- The definite article de /də/ the.

- The numerals alve /ɔlvə/ eleven, tolve /tolvə/ twelve, trije /trɛjə/ three and the quantifier folle /folə/ much; many; alve and tolve have the schwa-less variants alf /ɔlf/ and tolf /tolf/.

- The adverbs foare /foərə/ in front of the house; in the front room, folle /folə/ much; often, and tige /ti:ɣə/ very.

- The adjectives tige /ti:ɣə/ very good and jinse /jɪ:nsə/ yonder.

- The pronoun (de/dy) jinge /jɪŋə/ (the/that) one.

- The prepositions (be)tuske /(bə)tøskə/ between, binne /bɪnə/ inside, boppe /bopə/ above, bûte /butə/ outside, and njonke /njoŋkə/ next to. The prepositions (be)tuske, binne, bûte and njonke are, or are becoming, obsolete. At present, they are almost exclusively realized with final /-n/: (be)tusken, binnen, bûten and njonken. In Wâldfrysk, binne- and bûte- are productive as the left-hand member of compounds.

Secondly, Frisian has two singular definite articles, viz. de /də/ and it /ət/, both meaning the (see Gender marking). As to simplex nouns, the choice between de and it is largely arbitrary, that is to say, to a great extent the language-learning child simply must learn which definite article a given noun is associated with (see Hoekstra and Visser (1996) and Visser (2011) for more on this matter). For schwa-final nouns it is different, for they have the article de. This is nicely illustrated by 'minimal pairs' of nouns with the same meaning, one without final schwa and associated with it, one with final schwa and associated with de. Examples are given in (2):

| Examples of 'minimal pairs' with schwa-less it-nouns and schwa-final de-nouns | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it focht ~ de fochte | /foxt(ə)/ | liquid; moisture | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it gol ~ de golle | /ɡol(ə)/ | storage for hay or corn in a barn | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it koard ~ de koarde | /koəd(ə)/ | cord | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it oard ~ de oarde | /oəd(ə)/ | region; residence | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it sou ~ de souwe | /sɔw(ə)/ | riddle, sieve | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it tsjil ~ de tsjille | /tsjɪl(ə)/ | wheel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it wek ~ de wekke | /vɛk(ə)/ | hole (in the ice) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it festjebûs ~ de festjebûse | /-bus(ə)/ | watch pocket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Especially the last case is most revealing. It is the compound of festje /fɛst+tsjə/, the diminutive of fest /fɛst/ waistcoat, and (schwa-less) bûs /bus/ pocket. This is one of the few cases of a nominal compound in which the definite article is not determined by the right-hand member − here the de-word bûs −, but, instead, by the left-hand member, the diminutive (it-word) festje. If, however, the right-hand member is the schwa-final variant bûse /busə/, the compound has the article de.

Noun-final schwa therefore might be assumed to have the status of a suffix. Another indication of this is that it seems to determine the choice of the plural suffix. Like Dutch, Frisian has two plural suffixes, -en /-ən/ and -s /-s/ (see Regular plural formation). Dutch nouns ending in schwa can be pluralized with both -en and -s (the latter is gaining ground at the expense of the former), whereas they can only be pluralized with -en in Frisian. The Dutch noun bode /bodə/ messenger for instance has the plural forms boden and bodes, the Frisian counterpart boade /boədə/ on the other hand can only be pluralized as boaden. This leads Hoekstra (2011:291-296) to the assumption that in Frisian the choice of the plural suffix -en in the case of schwa-final nouns is not determined on phonological grounds, but that the suffix is selected by final schwa.

It is noted by Hoekstra (2011:293) that noun-final schwa also induces a plural in -en in case it is preceded by another schwa syllable. The nouns rigel /riɣəl/ row and keppel //kɛpəl/ group; herd; flock have the regular plural forms rigels and keppels. The schwa-final variants rigele /riɣələ/ and keppele /kɛpələ/, on the other hand, are pluralized as rigelen and keppelen, despite the fact that -en makes for a sequence of two schwa syllables − a lapse − here (see Alternating stress principle). Nouns ending in the suffix -ing //ɪŋ/ can be pluralized with either -en or -s (see variation of -en and -s). As noted by Hoekstra, however, nouns ending in the variant -inge /ɪŋə/ − few though they may be − only allow for a plural in -en, so printinge /prɪntɪŋə/ edition and rispinge //rɪspɪŋə/ harvesting; harvest have the plural forms printingen and rispingen (*printinges and *rispinges are out).

Though non-final schwa has suffix-like properties, it does not contribute to the meaning of the noun it is part of. Therefore, it may be considered an augment or stem extension. There are several indications for this. Firstly, some schwa-final nouns are in free variation with nouns without final schwa, as exemplified in the examples below:

| Examples of pairs of nouns with and without final schwa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| blabze | /blabzə/ | ~ | blabs | /blabz/ | mud, sludge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| dauwe | /dɔwə/ | ~ | dau | /dɔw/ | dew | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| doaze | /doəzə/ | ~ | doas | /doəz/ | box | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| dodde | /dodə/ | ~ | dod | /dod/ | slumber, drowse | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| fluite | /flʌytə/ | ~ | fluit | /flʌyt/ | flute | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| hekse | /hɛksə/ | ~ | heks | /hɛks/ | witch; shrew | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| jerke | /jɛrkə/ | ~ | jerk | /jɛrk/ | drake | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| klauwe | /klɔwə/ | ~ | klau | /klɔw/ | fluke | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| mudde | /mødə/ | ~ | mud | /mød/ | hectolitre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| poppe | /popə/ | ~ | pop | /pop/ | baby | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| rieme | /riəmə/ | ~ | riem | /riəm/ | belt | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| rouwe | /rɔwə/ | ~ | row | /rɔu/ | mourning | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| seale | /sɪələ/ | ~ | seal | /sɪəl/ | hall; room; ward | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| skrage | /skra:ɣə/ | ~ | skraach | /skra:ɣ/ | trestle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| snibbe | /snɪbə/ | ~ | snib | /snɪb/ | snappish girl | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| snotte | /snɔtə/ | ~ | snot | /snɔt/ | (nasal) mucus, discharge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| spjelde | /spjɛldə/ | ~ | spjeld | /spjɛld/ | pin; brooch | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| sprake | /spra:kə/ | ~ | spraak | /spra:k/ | speech; language | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| stjerre | /stjɛrə/ | ~ | stjer | /stjɛr/ | star | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| tippe | /tɪpə/ | ~ | tip | /tɪp/ | tip | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (t)sjoele | /(t)sjuələ/ | ~ | (t)sjoel | /(t)sjuəl/ | shovel | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| tuorre | /tworə/ | ~ | tuor | /twor/ | beetle | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ûne | /unə/ | ~ | ûn | /un/ | oven | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| welle | /vɛlə/ | ~ | wel | /vɛl/ | spring, well | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| wolle | /volə/ | ~ | wol | /vol/ | wool | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Secondly, if a noun with final schwa shows up as the left-hand member of a compound, it may or may not keep its schwa, examples of which are given in (4):

| Examples of nominal compounds with a schwa-final left-hand member with or without final schwa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a. | With final schwa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| moanne#ljocht | moonlight | (cf. | moanne | moon | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| tsjerke#ried | church council | (cf. | tsjerke | church | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| b. | Without final schwa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| bûs#jild | pocket money | (cf. | bûse | ) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| greid#boer | livestock farmer | (cf. | greide | grassland, meadow | ) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Thirdly, schwa is deleted in case the nouns in question undergo diminutive formation, a derivational process of great generality. There are three diminutive suffixes, whose distribution is solely determined by the final segment of the noun. The nouns in (1) above select their allomorph on the basis of the consonant preceding final schwa instead of final schwa itself, in which case they all would select the suffix -ke ( /-kə/), as do nouns ending in a vowel. This is shown in the table below:

| seachje [sɪəxjə] little saw | cf. eachje [ɪəxjə] little eye (from each /ɪəɣ/) |

| harkje [harkjə] little rake | cf. parkje [parkjə] little park (from park /park/) |

| plankje [plaŋkjə] little shelf | cf. drankje [draŋkjə] drink (from drank /draŋk/ spirits) |

| doaske [dwaskə] little box | cf. noaske [nwaskə] little nose (from noas /noəz/) |

| skjirke [skjɪrkə] little scissors | cf. blierke [bljɪrkə] little blister (from blier /bliər/) |

| tomke [tomkə] little thumb | cf. blomke [blomkə] little flower (from blom /blom/) |

| seage /sɪəɣə/ saw | seagje /sɪəɣjə/ to saw |

| flibe /flibə/ saliva | flybje /flibjə/ to slobber; to spit, to spew |

| besite /bəsitə/ visit | besytsje /bəsitjə/ [bəsitsjə] to visit |

| kroade /kroədə/ (wheel)barrow | kroadzje /kroədjə/ [kroədzjə] to wheel |

Since the diminutive suffixes and the verbal inflectional suffixes all contain schwa, the deletion of stem-final schwa might be considered as a rhythmically induced process, a sequence of two schwa-headed syllables being disfavoured. One would expect schwa deletion to be a variable and non-obligatory process, then. The above, however, shows that with respect to diminutive formation and noun-to-verb-conversion schwa deletion is obligatory and that it has morpho-phonological effects.

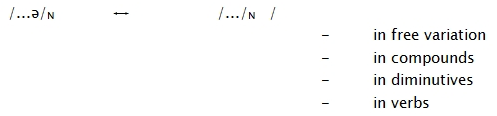

In general thus nouns ending in schwa have a schwa-less allomorph, used mainly in particular morphological contexts. We might express this relation as follows:

- 2011Meervoudsvorming in het Westerlauwers Fries en het Nederlands (en patroniemvorming in het Noord-Fries)Taal en Tongval63281-301

- 2011Meervoudsvorming in het Westerlauwers Fries en het Nederlands (en patroniemvorming in het Noord-Fries)Taal en Tongval63281-301

- 1996De en it-wurden yn it FryskUs Wurk4555-78

- 2011Historical gender change in West FrisianMorphology2131-56