- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Finite interrogative complement clauses may be introduced by the complementiserof if/whether or a wh-word (wanneer when, wat what, waar where, hoekom why, watter what/which). Interrogative complement clauses introduced by of íf/whether are general interrogatives (indirect yes/no-questions), as exemplified by (1), whereas interrogative complement clauses introduced by wh-words are specific interrogatives (indirect wh-questions), as exemplified by (2). Like finite declarative complement clauses (see the section on syntactic positions of finite declarative complement clauses), interrogative complement clauses are most frequently used as object clauses, but are also used as subject clauses and complementive clauses (discussed in more detail in the section on syntactic distribution).

| Ek vra [of dit seer was]. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I ask.PRS if.COMP it sore be.PRT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I ask if it was sore. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek vra [wat jou oorgekom het]. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I ask.PRS what you over.come.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I ask what happened to you. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

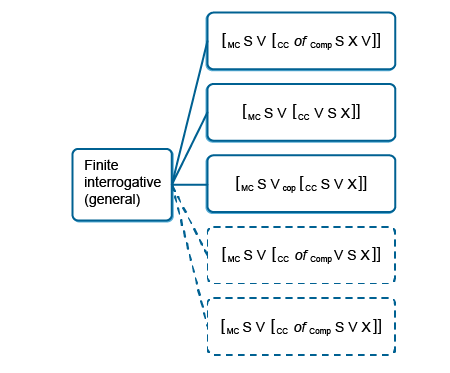

The main structural possibilities for general interrogative complement clauses are summarised in Figure 1, with non-standard constructions, or constructions particularly associated with spoken language, indicated by dashed lines.

General interrogative complement clauses are most prototypically introduced by the complementiser of if/whether, followed by dependent word order (verb-final, or SXV), as in (3).

| Ek wonder of hulle vriende na die partytjie kom. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(SUB) hulle vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie] [(VF) kom]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS if.COMP their friends to the party come.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if their friends will come to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The complementiser of if/whether may be omitted, in which case the word order in the complement clause reverts to main-clause interrogative word order (VSX), as in (4). This happens infrequently, but is more likely in spoken than in written Afrikaans.

| Ek wonder kom hulle vriende na die partytjie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(V1) kom] [(SUB) hulle vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS come.PRS their friends to the party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if their friends are coming to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A semantically and syntactically constrained, less schematic construction occurs where of if/whether is omitted following a copular verb in the complement-taking predicate, and the word order in the complement clause reverts to main-clause declarative word order (SVX), as in (5).

| Dit lyk my dit is 'n groot probleem deesdae. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) dit lyk my [(CC) [(SUB) dit] [(V2) is] [(COMPLM) 'n groot probleem] [(ADV) deesdae]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it seem.PRS me it be.PRS a big problem nowadays | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It seems to me it is a big problem nowadays. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A number of other (less acceptable) word-order variations in the general interrogative clause are attested, primarily in spoken language. There is a variant with of if/whether and main-clause interrogative word order (VSX). In this variant, the word order corresponds to that in (4), but the complementiser is present, as shown in (6).

| Ek wonder of kom hulle vriende na die partytjie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(V1) kom] [(SUB) hulle vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS if.COMP come.PRS their friends to the party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if their friends are coming to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In addition, there is a variant with of if/whether and main-clause declarative word order (SVX). The form frequently appears to be the consequence of processing strain, as it primarily (though not exclusively) occurs in spoken language where there is a modal verb present, as in (7).

| Hy het die musiek aan hom gestuur en gevra of hy sal woorde maak. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC1) hy het die musiek aan hom gestuur] en [(MC2) gevra [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(SUB) hy] [(V2) sal] [(OBJ) woorde] [(VF) maak]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| he have.AUX the music to him send.PST and ask.PST if.COMP he will.AUX.MOD words make.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| He sent the music to him and asked if he would make words. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

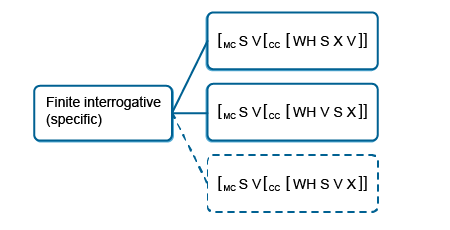

Specific interrogative complement clauses take two main construction forms: one with dependent (verb-last) word order (SXV), and one with independent interrogative word order (VSX). A non-standard form with main-clause declarative word order (SVX) is also attested. The construction forms for specific interrogative complement clauses are summarised in Figure 2, with non-standard constructions indicated by dashed rather than solid lines.

The more normative verb-final (SXV) specific interrogative complement construction is exemplified in (8), and is the major variant in written Afrikaans, although it occurs freely in spoken Afrikaans too.

| Ek wonder wanneer hulle vriende na die partytjie kom. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(WH) wanneer] [(SUB) hulle vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie] [(VF) kom]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS when their friends to the party come.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder when their friends will be coming to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The construction with main-clause interrogative word order (VSX) is exemplified in (9). This variant is the major variant in spoken Afrikaans, and does occur in written Afrikaans, although it is not very frequent in writing.

| Ek wonder wanneer kom hulle vriende na die partytjie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(WH) wanneer] [(V2) kom] [(SUB) hulle vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS when come.PRS their friends to the party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder when their friends will be coming to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In addition, a clearly non-standard form with declarative verb-second (SVX) word order is also attested, primarily in spoken language, as in (10).

| Maar daar was dae wat ek nie geweet het hoe ek gaan daai dae klaarkry nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) maar daar was dae wat ek nie geweet het [(CC) [(WH) hoe] [(SUB) ek] [(V2) gaan] [(OBJ) daai dae] [(VF) klaarkry]] nie] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| but there be.PRT days that I not know.PST have.AUX how I go.LINK those days finish.get.INF PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| But there were days that I didn’t know how I would get through those days. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

For general interrogative complement clauses, the construction with of if/whether and dependent word order (SXV) is most prototypical (Ponelis 1979:440,445). If the verb phrase consists of a single past or present tense lexical verb only, the verb is in the final position, as in (3) and (11), respectively.

| Ek wonder of hulle vriende by die partytjie was. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(SUB) hulle vriende] [(ADJ) by die partytjie] [(VF) was]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS if.COMP their friends at the party be.PRT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if their friends were at the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If the main verb is accompanied by a modal auxiliary, the modal verb occurs directly before the main verb, as in (12). The same holds for any aspectual verbs accompanying the main verb, as in (13).

| Ek wonder of ons hulle vriende na die partytjie moet uitnooi. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(SUB) ons] [(OBJ) hulle vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie] [(VF) moet uitnooi]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS if.COMP we their friends to the party must.AUX.MOD invite.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if we should invite their friends to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek wonder of my vriend al begin ontspan. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(SUB) my vriend] [(ADV) al] [(VF) begin ontspan]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS if.COMP my friend already start.LINK relax.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if my friend is starting to relax yet. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In past-tense constructions formed with the auxiliary het have, the auxiliary always occurs after the main verb in the past-tense form, as in (14). If a modal auxiliary is present in addition, it precedes the main verb, as shown in (15).

| Ek wonder of hulle ons vriende na die partytjie genooi het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(COMP) of] [(SUB) hulle] [(OBJ) ons vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie] [(VF) genooi het]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS if.COMP they our friends to the party invite.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if they invited our friends to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek wonder of hulle ons vriende na die partytjie sou genooi het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [CC [(COMP) of] [[(SUB) hulle] [(OBJ) ons vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie] [(VF) sou genooi het]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS if.COMP they our friends to the party will.AUX.MOD.PRT invite.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder if they would have invited our friends to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The complementiser of if/whether may be omitted. According to Ponelis (1979:440,454) and Feinauer (1990:116), the omission of of if/whether occurs only where the complement clause functions as predicate to the copular verbs lyk to appear/seem, voel to feel, skyn to seem and smaak to appear, in which case the word order in the complement clause reverts to main-clause declarative word order (SVX) as in (16a) (from Ponelis 1979:440). The alternative form with of if/whether and dependent word order (SXV) is exemplified in (16a'). In these cases, of if is interchangeable in meaning with asof as if/though.

The most frequent copular verb with general interrogative complement clauses is lyk to appear/seem. Its non-factivity predisposes it to an interrogative (“subjective”) complement clause with of if/whether or asof as if/though (see Ponelis 1979:222-223). However, lyk also occurs with declarative complement clauses, although infrequently (see the section on syntactic positions of the declarative complement clause). Interrogative complement clauses with lyk occur most frequently with of, as in (17) (around 56% of the time), with asof used 32% of the time, as in (18). The construction with the omitted complementiser, and declarative word order in the complement clause, occurs in only 12% of cases, and is illustrated in (19).

| Dit lyk of 'n beduidende ommeswaai plaasvind in die markaandeel van plaaslike produsente. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) [(SUB) dit] [(V2) lyk] [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(SUB) 'n beduidende ommeswaai] [(VF) plaasvind] [(ADV) in die markaandeel van plaaslike produsente]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it seem.PRS if.COMP a significant turnaround place.find.PRS in the market.share of local producers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It seems as if a significant turnaround is taking place in the market share of local producers. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit lyk asof die Golfstroom vinniger afkoel terwyl dit oor die Atlantiese Oseaan reis. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) [(SUB) dit] [(V2) lyk] [(CC) [(COMP) asof] [[(SUB) die Golfstroom] [(ADV) vinniger] [(VF) afkoel] [(ADV) terwyl dit oor die Atlantiese Oseaan reis]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it seem.PRS as.if.COMP the Gulf.stream faster down.cool.PRS while it over the Atlantic Ocean travel.PRS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It seems as if the Gulf Stream cools down faster while travelling across the Atlantic Ocean. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit lyk my daar is net nie geld nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) [(SUB) dit] [(V2) lyk] [(EXP) my] [(CC) [[(SUB) daar] [(V2) is] net nie [(OBJ) geld] nie]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it seem.PRS me there be.PRS just not money PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It seems to me there is just no money. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

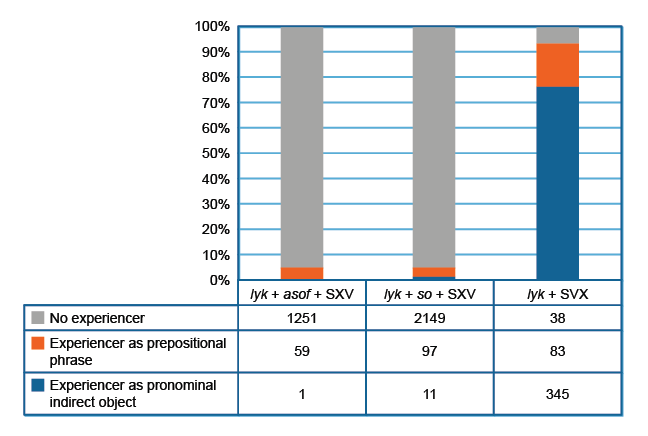

The construction without the complementiser, and with declarative word order, occurs proportionally more frequently in spoken language than in written language – in spoken language, it accounts for around 70% of all cases of lyk 'to seem/appear followed by an interrogative complement clause, whereas in written language this construction accounts for only around 10% of cases. The construction without the complementiser and declarative word order is also particularly strongly associated with the presence of an experiencer, either in the form of a pronominal indirect object (most frequently the first person my me), or in the form of a prepositional phrase, usually vir + pronoun to + pronoun (most frequently the first person my). An analysis of around 4,000 cases of lyk followed by an interrogative complement clause (from the Taalkommissiekorpus) demonstrates that the form without the complementiser is distinctly associated with the presence of an experiencer, and particularly in the form of pronominal indirect object. As is evident in Figure 3, the form lyk + of/asof seem/appear + if/whether OR as if/though and dependent word order typically has no marked experiencer present (as in (17) and (18)), with a small minority of cases including the experiencer in the form of a prepositional phrase (as in (20) and (21)). However, for lyk followed by independent declarative word order, the picture is markedly different, with the prototypical construction including an experiencer in the form of a pronominal indirect object (usually my, as in (19) and (22), or (in a smaller number of cases) in the form of a prepositional phrase (as in (23). Cases with no experiencer present (illustrated in (24) do occur, but are a minority.

| En dit lyk vir ons asof dit amper nie die ink werd is nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| en [(MC) [(SUB) dit] [(V2) lyk] [(EXP) vir ons] [(CC) [(COMP) asof] [[(SUB) dit] amper nie die ink werd [(VF) is] nie]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| and it seem.PRS to us as.if.COMP it almost not the ink worth be.PRS PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| And it seems to us as if it is almost not worth the ink. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In hierdie stadium lyk dit vir my of die skoolstelsel grootliks die oorsaak is van Karien se emosionele probleme. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) [(ADV) in hierdie stadium] [(V2) lyk] [(SUB) dit] [(EXP) vir my] [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(SUB) die skoolstelsel] grootliks die oorsaak [(V2) is] van Karien se emosionele probleme]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| in this stage seem.PRS it to me if.COMP the school.system largely the cause be.PRS of Karien PTCP.POSS emotional problems | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| At this stage it seems to me as if the school system is largely the cause of Karien’s emotional problems. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maar dit lyk my die onderwyseres het nie veel notisie van ons geneem nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| maar [(MC) [(SUB) dit] [(V2) lyk] [(EXP) my] [(CC [[(SUB) die onderwyseres] [(V2) het] nie veel notisie van ons [(VF) geneem] nie]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| but it seem.PRS me the teacher.F have.AUX not much notice of us take.PST PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| But it seems to me as if the teacher didn’t take much notice of us. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dit lyk vir my hy weet nie veel van rugby af nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) [(SUB) dit] [(V2) lyk] [(EXP) vir my] [(CC) [[(SUB) hy] [(V2) weet] nie veel van rugby af nie]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| it seem.PRS to me he know.PRS not much of rugby off PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| It seems to me as if he doesn’t know much about rugby. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dan lyk dit daar is 'n konsensus: die rugbybase sal hul kant moet bring. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) [(ADV) dan] [(V2) lyk] [(SUB) dit] [(CC) [[(SUB) daar] [(V2) is] 'n konsensus: die rugbybase sal hul kant moet bring]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| then seem.PRS it there be.PRS a consensus: the rugby.bosses will.AUX.MOD their side must.AUX.MOD bring.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Then there seems to be a consensus: the rugby bosses will have to do their part. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The above suggests that the construction with the copular verb as matrix verb, no complementiser, and declarative word order constitutes a case where the complement clause expresses a factive claim, with the complement-taking predicate functioning as an epistemic hedge with a function of intersubjective coordination. This is further supported by the occurrence of the construction without the dummy subject dit it, as in (25).

| Lyk my jy het nie goed geslaap nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) [(V2) lyk] [(EXP) my] [(CC) [[(SUB) jy] [(V2) het] nie goed [(VF) geslaap] nie]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| seem.PRS me you have.AUX not good sleep.PST PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Seems to me you’ve not slept well. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Beyond this specialised construction, the omission of the complementiser of if/whether does also occur in more general contexts – in other words, where the general interrogative complement clause is used as an object clause rather than a predicate clause (in contrast to Ponelis (1979) and Feinauer (1990)) with the word order in the complement clause reverting to independent interrogative word order (VSX). However, this is an infrequent phenomenon that is particularly associated with spoken language. Unlike the specialised construction outlined above, this construction is a general case of complementiser omission, with thematic prominence shifted to the complement clause. The interrogative word order is retained in the complement clause, which indicates that the factivity of the clause is not presupposed. Some attested examples are listed in (26) and (27).

| Hulle vra vir haar was Boet Ewerson vandag hier. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) hulle vra vir haar [(CC) [(Vpst) was] [(SUB) Boet Ewerson] [(ADV) vandag hier]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| they ask.PRS for her be.PRT Boet Ewerson today here | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| They ask her whether Boet Ewerson was here today. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hy het vir hom die môre gevra weet hy hoe om toast te maak. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) hy het vir hom die môre gevra [(CC) [(V1) weet] [(SUB) hy] [(CC) [hoe om toast te maak]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| he have.AUX for him the morning ask.PST know.PRS he how for.COMP toast PTCL.INF make.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| He asked him in the morning whether he knew how to make toast. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are two less standard constructions for the general interrogative complement clause. The first is characterised by the presence of the complementiser of if/whether, followed by independent interrogative word order (VSX), as in (28).

| Ons weet nie of sal ons môre opstaan nie. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ons weet nie [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(V1) sal] [(SUB) ons] [(ADV) môre] [(VF) opstaan]]] nie] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| we know.PRS not if.COMP will.AUX.MOD we tomorrow arise.INF PTCL.NEG | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| We don’t know if we’ll get up tomorrow. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PCSA, adapted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The second is characterised by main-clause declarative word order with of if/whether, as in (7).

Feinauer (1989:31) finds that these non-standard word-orders are extremely infrequent in her data, a finding we confirmed in our analysis of the Ponelis Corpus of Spoken Afrikaans, where the non-normative word orders occur only in 4% of the total number of general interrogative complement clauses. In the Taalkommissiekorpus and the Maroelakorpus, these constructions occur at negligible frequencies.

Where non-normative word order does occur in general interrogative complement clauses with of, it more frequently takes the form with declarative rather than interrogative word order, as in (7). These forms appear to be the consequence of processing strain, as they are often, though not exclusively, associated with grammatical environments of increased complexity. In the normative literature, the construction with of and main-clause interrogative order is discussed and clearly proscribed from the 1950s onwards, with less attention to of and main-clause declarative word order. The non-normative construction is usually attributed to spoken-language influence (Van der Merwe and Ponelis 1982:141) or to the influence of English via the second-language Afrikaans of native speakers of English (Prinsloo and Odendal 1995:136). However, an analysis of the Afrikaans Historical Corpus (Kirsten 2016) demonstrates that non-normative word orders with of at no point became entrenched constructions in written language. In the period 1911-1920, non-normative word orders account for only 3% of general interrogative complement clauses (see (29)), and in subsequent periods the frequency is 1% or less.

| Die bevolking werd in onkunde gehou van wat in Europa gebeur was, en wis nie beter of Nederland was deur Frankrijk verower… | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC1) die bevolking werd in onkunde gehou van wat in Europa gebeur was], en [(MC2) [(V2) wis] nie beter [(CC) [(COMP) of] [[(SUB) Nederland] [(V2) was] deur Frankrijk [(VF) verower]]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the population be.AUX.PASS.PRS in ignorance keep.PASS of what in Europe happen.PST be.AUX.PERF and know.PST not better if.COMP Netherlands be.AUX.PASS.PRT by France defeat.PASS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The population was kept ignorant of what was happening in Europe, and did not know whether the Netherlands were conquered by France. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| HCSA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wh-interrogatives show more variability between the normatively preferred verb-final word order, and the verb-second order that characterises main-clause wh-interrogatives than is the case for general interrogatives. There is a clear register differentiation in the frequency of the two constructions, with the verb-final order by far the dominant form in written Afrikaans, with spoken Afrikaans demonstrating more variability.

For the more normative verb-final construction, if the verb phrase consists of a single past or present-tense lexical verb only, the verb occurs in the final position, as in (8) and (30).

| Ek wonder hoekom hulle by die partytjie was. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(WH) hoekom] [(SUB) hulle] [(ADJ) by die partytjie] [(VF) was]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS why they at the party be.PRT | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder why they were at the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

If the main verb is accompanied by a modal auxiliary or aspectual verb, the modal or aspectual verb occurs directly before the main verb, as in (31) and (32).

| Ek wonder hoekom hulle vriende na die partytjie moet kom. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(WH) hoekom] [(SUB) hulle vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie] [(VF) moet kom]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS why their friends to the party must.AUX.MOD come.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder why their friends have to come to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek wonder wanneer hulle uiteindelik begin ontspan. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(WH) wanneer] [(SUB) hulle] [(ADV) uiteindelik] [(VF) begin ontspan]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS when they eventually start.LINK relax.INF | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder when they will eventually start relaxing. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In past-tense constructions formed with the auxiliary het have, the auxiliary always occurs after the main verb in the past-tense form, as in (33). If a modal auxiliary is present in addition, it precedes the main verb, as shown in (34).

| Ek wonder hoekom hulle ons vriende na die partytjie genooi het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(WH) hoekom] [(SUB) hulle] [(OBJ) ons vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie] [(VF) genooi het]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS why they our friends to the party invite.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder why they invited our friends to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ek wonder hoekom hulle ons vriende na die partytjie sou genooi het. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| [(MC) ek wonder [(CC) [(WH) hoekom] [(SUB) hulle] [(OBJ) ons vriende] [(ADV) na die partytjie] [(VF) sou genooi het]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder.PRS why they our friends to the party will.AUX.MOD.PRT invite.PST have.AUX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| I wonder why they would have invited our friends to the party. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Biberauer (2002:37) argues that the specific interrogative complement clause with main-clause interrogative word order is an established construction in spoken Afrikaans, occurring at high frequency (around 70%). Feinauer (1989:31) similarly reports a high frequency in her spoken corpus, and we find, in the Ponelis Corpus of Spoken Afrikaans, that this construction accounts for around 47% of all instances. It is also reasonably frequent in unedited written Afrikaans – in the Maroela Comment Corpus, it accounts for 31% of all cases. On the basis of these data, it appears that the two main word-order variants of the specific interrogative complement clause may be regarded as two entrenched constructional forms from which speakers make a selection. The two constructions appear to be functionally differentiated, in a similar way as the two normative variants of the declarative complement clause are functionally differentiated, with the main-clause interrogative word order having the effect of shifting the informational focus to the complement clause, and the complement-taking predicate functioning as an interpersonal frame for the complement clause (see Thompson 2002; Verhagen 2005).

Biberauer (2002) argues that in contemporary spoken Afrikaans, there is a process of language change underway, with the variant with main-clause interrogative word order becoming increasingly dominant. An analysis of a twentieth-century corpus of Afrikaans does not provide a definitive answer to this question: in the written sources included in the Historical Corpus of Standard Afrikaans, specific interrogatives with main-clause interrogative word orders are consistently attested at relatively low, but non-negligible frequencies, ranging from 3% to 8%, with contemporary written Afrikaans (as reflected in the Taalkomissiekorpus) demonstrating a frequency of around 6% of the variant with main-clause interrogative word order. The diachronic variation evident in written language is therefore not indicative of a long-term change.

The lower frequency of the construction with main-clause interrogative word order in written as compared to spoken registers raises the question of whether the differences in frequency might be ascribed to a normative effect that comes into play in edited written registers, or whether there is a functional explanation for the register difference. While the normativity explanation seems likely, and has been proposed by Biberauer (2002), an analysis of prescriptive sources we undertook demonstrates that the question of word order in the specific interrogative complement clause is hardly raised in prescriptive sources, and where it is, there is conflicting advice. A proscription on this word order is added in the second edition of "Skryf Afrikaans van A-Z" (Müller and Pistor 2011); however, in the seventh edition of "Die korrekte woord" (Van der Merwe and Ponelis 1991), the VSX order in specific interrogative complement clauses is regarded as acceptable in both spoken and written language.

Given the recentness of prescriptive advice on the VSX order in specific interrogative complement clauses, and the conflicting views evident, it may well be that normativity is not the only explanation for the differences in frequency of this construction in spoken and written language. Rather, it may be the case that the construction is more frequent in spoken language than in written language, since in the former the interpersonal function is more dominant than the propositional function.

Lastly, a clearly non-normative word order occurs at very low frequencies, where main-clause declarative word order (SVX) is used in the complement clause, as in example (10). While this appears to occur primarily in spoken language, it also occasionally occurs in written registers, as in (35). This variant does not appear to be an established construction; rather it appears to be associated with contexts of increased grammatical complexity which induce processing strain.

| Die rede waarom ek skryf, is omdat ek wil weet hoe 'n mens moet aansoek doen vir die pos van president. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| die rede waarom ek skryf, is [(COMPLM) omdat [(SUB) ek] [(V2) wil] [(VF) weet] [(CC) [(WH) hoe] [(SUB) 'n mens] [(VF) moet aansoek doen] vir die pos van president]]] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| the reason why I write.PRS be.PRS because I want.to.AUX.MOD know.INF how a human must.AUX.MOD application do.INF for the post of president | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The reason why I am writing, is because I want to know how one should apply for the job of president. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TK | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: Is this a unitary phenomenon?Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics3419-69

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: Is this a unitary phenomenon?Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics3419-69

- 2002Verb second in Afrikaans: Is this a unitary phenomenon?Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics3419-69

- 1990Skoon afhanklike sinne in Afrikaanse spreektaal.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde8116-120,

- 1990Skoon afhanklike sinne in Afrikaanse spreektaal.South African Journal of Linguistics = Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Taalkunde8116-120,

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinneSouth African Journal of Linguistics7(1)30-37

- 1989Plasing in Afrikaanse afhanklike sinneSouth African Journal of Linguistics7(1)30-37

- 2016Grammatikale verandering in Afrikaans van 1911-2010.Thesis

- 2011Skryf Afrikaans van A tot ZPharos

- 1979Afrikaanse sintaksis.Van Schaik

- 1979Afrikaanse sintaksis.Van Schaik

- 1979Afrikaanse sintaksis.Van Schaik

- 1979Afrikaanse sintaksis.Van Schaik

- 1979Afrikaanse sintaksis.Van Schaik

- 1979Afrikaanse sintaksis.Van Schaik

- 1995Afrikaans op sy besteVan Schaik

- 2002“Object complements and conversation”: Towards a realistic accountStudies in Language26(1)125-164

- 1982Die korrekte woord: Afrikaanse taalkwessies.Van Schaik

- 1982Die korrekte woord: Afrikaanse taalkwessies.Van Schaik

- 2005Constructions of intersubjectivity: discourse, syntax, and cognitionOxford/New YorkOxford University Press