- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

This section discusses some of the semantic classifications of main verbs proposed over the last fifty years. The discussion starts with Vendler's (1957) distinction between states, activities, achievements and accomplishments, which has been the starting point for most semantic classifications proposed later. A problem with Vendler's classifications is that it became clear very quickly that it is not a classification of main verbs but of events expressed by larger structures headed by these main verbs. For example, one of the features that Vendler uses in his classification (and which is taken over in one form or another in most classifications of later date) is whether the event denoted by the verb has some logically implied endpoint, and the examples in (52) show that this need not be an inherent property of the verb itself but may be (partly) determined by, e.g., the internal argument of the verb: a singular indefinite object headed by a count noun introduces an inherent endpoint of the event denoted by the verb eten'to eat' (the event ends when the roll in question has been fully consumed), whereas a plural indefinite object does not (the endpoint depends on the number of rolls that Jan will consume).

| a. | Jan | eet | een broodje | met kaas. | |

| Jan | eats | a roll | with cheese | ||

| 'Jan is eating a role with cheese.' | |||||

| b. | Jan eet | broodjes | met kaas. | |

| Jan eats | rolls | with cheese | ||

| 'Jan is eating rolls with cheese.' | ||||

Another problem with discussing the semantic classifications proposed since Vendler (1957) is that they often involve different dividing lines between the categories so that certain verbs may be categorized differently within the different proposals. Nevertheless, it is useful to discuss some specific proposals, given that the tradition that started with Vendler (1957) is still very much alive and continues to play an important role in present-day linguistics. Furthermore, we will see that a number of more recent proposals are formulated in such terms that make it possible to relate the semantic classification to the syntactic classification proposed in Section 1.2.2.

Verbs are often classified according to the Aktionsart (which is sometimes also called inner aspect) they express. The term Aktionsart refers to the internal temporal organization of the event denoted by the verb and thus involves questions like (i) whether the event is construed as occurring at a single point in time (momentaneous aspect) or as evolving over time (durative aspect); (ii) whether the event is inherently bounded in time, and, if so, whether the event is bounded at the beginning (ingressive/inchoative aspect), at the end (terminative aspect) or both; (iii) whether the verb expresses a single event or a series of iterated events, etc; see Lehmann (1999) for further distinctions and more detailed discussion.

| a. | Momentaneous aspect: exploderen'to explode', botsen'to collide' |

| b. | Durative aspect: lachen'to laugh', wandelen'to walk/hike', zitten'to sit' |

| c. | Inchoative aspect: ontbranden'to ignite', ontkiemen'to germinate' |

| d. | Terminative aspect: doven'to extinguish', smelten'to melt', vullen'to fill' |

| e. | Iterative aspect: bibberen'to shiver', stuiteren'to bounce repeatedly' |

The Aktionsarts in (53) do not, however, necessarily define mutually exclusive verb classes. Bounded events expressed by the inchoative and terminative verbs in (53c&d), for example, also evolve over time and are therefore durative as well. It therefore does not come as a surprise that there have been attempts to develop a more sophisticated semantic classification based on the aspectual properties of verbs.

Probably the best-known and most influential classification of main verbs is the one developed by Vendler (1957), who distinguishes the four aspectual classes in (54).

| a. | Activities: bibberen'to shiver', denken (over)'to think (about)', dragen'to carry', duwen'to push', hopen'to hope', eten (intr.) 'to eat', lachen'to laugh', lezen (intr.) 'to read', luisteren'to listen',praten'to talk', rennen'to run', schrijven (intr.) 'to write', sterven'to die', wachten (op)'to wait (for)', wandelen'to walk', zitten'to zit' |

| b. | Accomplishments: bouwen'to build', eten (tr.) 'to eat', koken (tr.) 'to cook', lezen (tr.) 'to read', opeten'to eat up', schrijven (tr.) 'to write', oversteken'to cross', verbergen'to hide', verorberen'to consume', zingen (tr.) 'to sing' |

| c. | States: begrijpen'to understand', bezitten'to own', haten'to hate', hebben'to have', horen'to hear', geloven'to believe', houden van'to love', kennen'to know', leven'to live', verlangen'to desire', weten'to know' |

| d. | Achievements: aankomen'to arrive', beginnen'to start', bereiken'to reach', botsen'to collide', herkennen'to recognize', ontploffen'to explode', ontvangen'to receive', overlijden'to die', zich realiseren'to realize', stoppen'to stop', opgroeien'to grow up', vinden'to find', winnen'to win', zeggen'to say' |

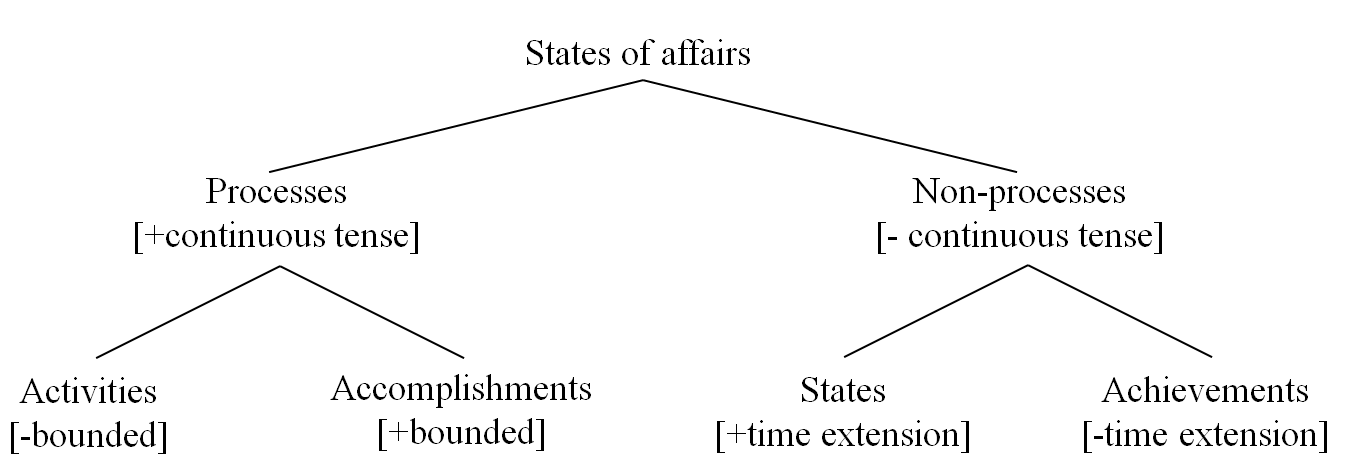

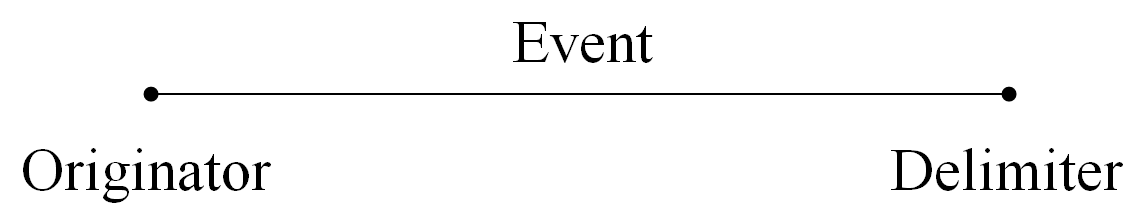

Vendler argues that activities and accomplishments can be grouped together as processes and that states and achievements can be grouped together as non-processes, as depicted in Figure 3.

The distinctions shown in Figure 3 are based on a number of semantic properties, which will be discussed in the following subsections.

Vendler claims that verbs fall into two supercategories, which he calls processes and non-processes. Process verbs denote events which involve a specific internal dynamism over time and are characterized by the fact that they can be used to provide an answer to interrogative, progressive aan het + infinitive constructions like Wat is Marie aan het doen?'What is Marie doing?'; see constructions like Wat is Marie aan het doen?'What is Mary doing?'; see also Booij (2010:ch.6).

| a. | Marie | is naar Peter | aan | het | luisteren. | activity | |

| Marie | is to Peter | aan | het | listen | |||

| 'Marie is listening to Peter.' | |||||||

| b. | Marie | is haar boterham | aan | het | opeten. | accomplishment | |

| Marie | is her sandwich | aan | het | prt.-eat | |||

| 'Marie is eating her sandwich.' | |||||||

| c. | * | Marie | is van spinazie | aan | het | houden. | state |

| Marie | is of spinach | aan | het | like | |||

| Compare: '*Marie is liking spinach.' | |||||||

| d. | * | Marie | is aan | het | aankomen. | achievement |

| Marie | is aan | het | prt.-arrive | |||

| 'Marie is arriving.' | ||||||

Vendler divides the processes in activities and accomplishments on the basis of whether or not the event has a logically implied endpoint. Activities like luisteren'to listen' are open-ended; the event referred to in (55a) has no natural termination point and can, at least in principle, last for an infinitely long period of time. Accomplishments like opeten'to eat up', on the other hand, involve some inherent endpoint; the event referred to in (55b) is completed when the sandwich referred to by the object has been fully consumed.

This difference can be made more conspicuous by means of considering the validity of the entailments in (56). When we observe at a specific point in time that (56a) is true, we may conclude that (56a') is also true, but the same thing does not hold for the (b)-examples. This shows that in the case of an accomplishment like opeten'to eat up' it is not sufficient for the subject of the clause to be involved in a specific activity, but that reaching the logically implied endpoint is a crucial aspect of the meaning.

| a. | Marie | is naar Peter | aan | het | luisteren. ⇒ | activity | |

| Marie | is to Peter | aan | het | listen | |||

| 'Marie is listening to Peter.' | |||||||

| a'. | Marie heeft | naar Peter | geluisterd. | |

| Marie has | to Peter | listened | ||

| 'Marie has listened to Peter.' | ||||

| b. | Marie | is haar boterham | aan | het | opeten. ⇏ | accomplishment | |

| Marie | is her sandwich | aan | het | prt.-eat | |||

| 'Marie is finishing her sandwich.' | |||||||

| b'. | Marie heeft | haar boterham | opgegeten. | |

| Marie has | her sandwich | prt.-eaten | ||

| 'Marie has finished her sandwich.' | ||||

The same point can be illustrated by question-answer pairs like those in (57), which show that accomplishments can be used in interrogatives of the form Hoe lang kostte het ...te Vinfinitive?'How long did it take to V ...?', which question the span of time that was needed to reach the logically implied endpoint, whereas activities cannot. The primed examples provide the corresponding answers to the questions.

| a. | * | Hoe lang | kostte | het | naar je leraar | te luisteren? | activity |

| how long | took | it | to your teacher | to listen | |||

| Compare: '*How long did it take to listen to your teacher?' | |||||||

| a'. | * | Het | kostte | een uur | naar mijn leraar | te luisteren. |

| it | cost | an hour | to my teacher | to listen | ||

| Compare: '*It took an hour to listen to my teacher.' | ||||||

| b. | Hoe lang | kostte | het | je maaltijd | op | te eten? | accomplishment | |

| how long | took | it | your meal | prt. | to eat | |||

| 'How long did it take to finish your meal?' | ||||||||

| b'. | Het | kostte | 10 minuten | mijn maaltijd | op | te eten. | |

| it | cost | 10 minutes | my meal | prt. | to eat | ||

| 'It took 10 minutes to finish my meal.' | |||||||

The question-answer pairs in (58) show that the opposite holds for interrogatives of the type Hoe lang auxfinite ...V?'For how long did ... V ...?', which simply question the span of time during which the activity took place; such pairs can be used with verbs denoting activities but not with verbs denoting accomplishments.

| a. | Hoe lang | heb | je | naar je leraar | geluisterd? | activity | |

| how long | have | you | to your teacher | listened | |||

| 'For how long did you listen to your teacher?' | |||||||

| a'. | Ik | heb | een uur | (lang) | naar mijn leraar | geluisterd. | |

| I | have | an hour | long | to my teacher | listened | ||

| 'I have listened to my teacher for an hour.' | |||||||

| b. | * | Hoe lang | heb | je | je maaltijd | opgegeten? | accomplishment |

| how long | have | you | your meal | prt.-eaten |

| b'. | * | Ik | heb | een uur | (lang) | mijn maaltijd | opgegeten. |

| I | have | an hour | long | my meal | prt.-eaten |

Another, but essentially identical, test that is often used to distinguish activities and accomplishments is the addition of specific types of temporal adverbial phrases: adverbial phrases like gedurende een uur'during an hour' or een uur lang'for an hour', which refer to the span of time during which the event denoted by the verb takes place, are typically used with activities; adverbial phrases like binnen een uur'within an hour', which measure the span of time that is needed to reach a logically implied endpoint, are typically used with accomplishments.

| a. | Jan luisterde | gedurende/*binnen een uur | naar zijn leraar. | activity | |

| Jan listened | during/within an hour | to his teacher | |||

| 'Jan listened to his teacher for an hour.' | |||||

| b. | Jan at | zijn maaltijd | binnen/*gedurende | vijf minuten | op. | accomplishment | |

| Jan ate | his meal | within/during | five minutes | prt. | |||

| 'Jan finished his meal in an hour.' | |||||||

The (in)validity of the inferences in (56) and the selection restrictions on adverbial phrases in (59) are related to the fact that activities can normally be divided into shorter subevents that can again be characterized as activities: if I have been listening to Peter for an hour, I also have been listening to Peter during the first five minutes of that hour, the second five minutes of that hour, etc. This does not hold for accomplishments due to the fact that they crucially refer to the implied endpoint of the event: if I have finished my meal within five minutes, I did not necessarily finish my meal within the first, second, third or fourth minute of that time interval; cf. Dowty (1979:ch.3).

Vendler claims that states differ from achievements in that the former have a temporal extension, whereas the latter do not. This can be made clear by using the questions Hoe lang V finite Subject ... al ...?'For how long has Subject already Vpart ...'. The examples in (60) show that states are easily possible in such question-answer pairs, whereas achievements are not.

| a. | Hoe lang | weet | Jan | al | wie | de dader | is? | state | |

| how long | knows | Jan | already | who | the perpetrator | is | |||

| 'For how long has Jan known who the perpetrator is?' | |||||||||

| a'. | Jan weet | al | een paar weken | wie | de dader | is. | |

| Jan know | already | a couple of weeks | who | the perpetrator | is | ||

| 'Jan has known for a couple of weeks who the perpetrator is.' | |||||||

| b. | *? | Hoe lang | herkent | Peter de dader | al? | achievement |

| how long | recognizes | Peter the perpetrator | already |

| b'. | *? | Jan | herkent | de dader | al | een paar weken. |

| Jan | recognizes | the perpetrator | already | a couple of weeks |

Achievements occur instead in question-answer pairs that involve the actual moment at which the event took place, which is clear from the fact that they can readily be used in questions like Hoe laat Vfinite Subject ...?'At what time did Subject V ...?'.

| a. | Hoe laat | herkende | Peter de dader? | achievement | |

| how late | recognized | Peter the perpetrator | |||

| 'At what time did Peter recognize the perpetrator?' | |||||

| a'. | Peter herkende | de dader | om drie uur. | |

| Peter recognized | the perpetrator | at three oʼclock |

| b. | Hoe laat | ontplofte de bom? | achievement | |

| how late | exploded the bomb | |||

| 'At what time did the bomb explode?' | ||||

| b'. | De bom | ontplofte | om middernacht. | |

| the bomb | exploded | at midnight |

States, on the other hand, normally do not readily enter questions of this type, and, if they do, the answer to the question refers to some moment at which something has happened that resulted in the obtainment of the state denoted by the verb.

| a. | *? | Hoe laat | houd | je | van Jan? | state |

| how late | love | you | of Jan | |||

| 'At what time do you love Jan?' | ||||||

| b. | Hoe laat | weet | je | of | je | geslaagd | bent? | state | |

| how late | know | you | whether | you | passed | are | |||

| 'At what time do you know whether you passed the exam/get the results of the exams?' | |||||||||

Note that we have labeled the top node in Figure 3, repeated below for convenience, not as verbs, but as states of affairs. The reason is that, although Vendler seems to have set out to develop a classification of verbs, he actually came up with a classification of different types of states of affairs; see, e.g., Verkuyl (1972) and Dowty (1979).

For example, it seems impossible to classify the verb schrijven'to write' without additional information about its syntactic environment. The judgments on the use of the adverbial phrases of time in example (63) show that schrijven functions as an activity if it is used as an intransitive verb, but as an accomplishment if it is used as a transitive verb.

| a. | Jan | schreef | gedurende/*binnen | een uur. | activity | |

| Jan | wrote | during/within | an hour | |||

| 'Jan was writing for an hour.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan schreef | het artikel | binnen/*gedurende | een uur. | accomplishment | |

| Jan wrote | the article | within/during | an hour | |||

| 'Jan wrote the article within an hour.' | ||||||

It is not, however, simply a matter of the adicity of the verb. First, the examples in (64) show that properties of the object may also play a role: the interpretation depends on whether the object refers to an unspecified or a specified quantity of books; cf. Verkuyl (1972/1993), Dowty (1979) and Dik (1997). In the (a)-examples this is illustrated by means of the contrast evoked by a bare plural noun phrase and a plural noun phrase preceded by a cardinal numeral, and in the (b)-examples by means of the contrast evoked by noun phrases headed by, respectively, a non-count and a singular count noun.

| a. | Jan schreef | gedurende/*binnen | twee jaar | boeken. | activity | |

| Jan wrote | during/within | two year | books |

| a'. | Jan schreef | binnen/*gedurende | twee jaar | drie boeken. | accomplishment | |

| Jan wrote | within/during | two year | three books |

| b. | Jan at | spaghetti. | activity | |

| Jan ate | spaghetti |

| b'. | Jan at | een bord spaghetti. | accomplishment | |

| Jan ate | a plate [of] spaghetti |

A similar effect may arise in the case of verbs like ontploffen'to explode'. If the subject is a singular noun phrase, we are dealing with a momentaneous event, that is, with an achievement. If the subject is a definite plural, however, the adverbial test suggests that we can also be dealing with an activity, and if the subject is an indefinite plural the adverbial test suggests that we can only be dealing with an activity.

| a. | De bom | ontplofte | om drie uur/*de hele dag. | achievement | |

| the bomb | exploded | at three oʼclock/the whole day |

| b. | De bommen | ontploften | om drie uur/de hele dag. | achievement or activity | |

| the bombs | exploded | at three oʼclock/the whole day |

| c. | Er | ontploften | de hele dag/??om drie uur | bommen. | activity | |

| there | exploded | the whole day/at three oʼclock | bombs | |||

| 'There were bombs exploding the whole day.' | ||||||

Second, the addition of elements other than objects may also have an effect on the interpretation; the examples in (66) show, for instance, that adding a complementive like naar huis'to home' or a verbal particle like terug'back' turns an activity into an accomplishment.

| a. | Jan wandelde | twee uur lang/*binnen twee uur. | activity | |

| Jan walked | two hours long/within two hours | |||

| 'Jan walked for two hours.' | ||||

| b. | Jan wandelde | binnen twee uur/*twee uur lang | naar huis. | accomplishment | |

| Jan walked | within two hours/two hours long | to home | |||

| 'Jan walked home within two hours.' | |||||

| b'. | Jan wandelde | in twee uur/*twee uur lang | terug. | accomplishment | |

| Jan walked | in two hours/two hours long | back | |||

| 'Jan walked back within two hours.' | |||||

Third, the examples in (67) illustrate that the categorial status of the complement of the verb may also affect the aspectual nature of the event: whereas the nominal complement in (67b) triggers an accomplishment reading, the PP-complement triggers an activity reading.

| a. | Jan dronk de wijn. | accomplishment | |

| Jan drank the wine |

| b. | Jan dronk van de wijn. | activity | |

| Jan drank of the wine |

The examples in (68) show a somewhat similar alternation between states and activities. The (a)-examples show that if the verb denken'to think' takes a propositional complement like a clause, it cannot occur in the progressive aan het + infinitive + zijn construction, and we may therefore conclude that we are dealing with a state. The (b)-examples show that if the verb denken selects a PP-complement, it can occur in the progressive construction, and that we are thus dealing with an activity. The (c)-examples show that we get a similar meaning shift if we supplement the verb with the verbal particle na.

| a. | Marie denkt | dat | Jan | een deugniet | is. | state | |

| Marie thinks | that | Jan | a rascal | is | |||

| 'Marie thinks that Jan is a rascal.' | |||||||

| a'. | * | Marie is aan het | denken | dat Jan een deugniet is. |

| Marie is aan het | think | that Jan a rascal is |

| b. | Marie denkt | over het probleem. | activity | |

| Marie thinks | about the problem | |||

| 'Marie is thinking about the problem.' | ||||

| b'. | Marie is | over het probleem | aan het | denken. | |

| Marie is | about the problem | aan het | think |

| c. | Marie denkt | na. | activity | |

| Marie thinks | prt. | |||

| 'Marie is pondering.' | ||||

| c'. | Marie is | aan het | nadenken. | |

| Marie is | aan het | prt.-think |

The previous subsections have briefly discussed some distinctive semantic properties of verbs and events that Vendler (1957) used to motivate his classification in Figure 3. This discussion leads to the following characterizations of the four subclasses.

| a. | Activities +continuous tense, -bounded: events that go on for some time in a homogeneous way in the sense that they do not proceed toward a logically necessary endpoint. |

| b. | Accomplishments +continuous tense, +bounded: events that go on for some time in a non-homogeneous way in the sense that they proceed toward a logically necessary endpoint. |

| c. | States -continuous tense, +time extension: stable situations that last for some period of time. |

| d. | Achievements -continuous tense, -time extension: events that are perceived as occurring momentaneously. |

One problem with this classification is that the features used are in fact more widely applicable than simply for making the distinctions given in (69). The feature ±bounded, for example, may be just as relevant for states and achievements as for activities and accomplishments. In fact, this feature may group states and activities as unbounded, and accomplishments and achievements as bounded states of affairs. The examples in (70) show that states behave like activities in that they can be used in perfective questions of the form Hoe lang auxfinite ...V?'For how long did ... V ...?', whereas accomplishments and achievements cannot.

| a. | Hoe lang | heeft | hij | naar zijn leraar | geluisterd? | activity | |

| how long | has | he | to his teacher | listened | |||

| 'For how long did he listen to his teacher?' | |||||||

| b. | * | Hoe lang | heeft | hij | zijn maaltijd | opgegeten? | accomplishment |

| how long | has | he | his meal | prt.-eaten |

| c. | Hoe lang | heeft | hij | van spinazie | gehouden? | state | |

| how long | has | he | of spinach | liked | |||

| 'For how long did he like spinach?' | |||||||

| d. | * | Hoe lang is | de bom | ontploft? | achievement |

| how long has | the bomb | exploded |

If an interrogative phrase refers to a specific time, on the other hand, the acceptability judgments are reversed. This is shown in (71) by means of the adverbial phrase hoe laat'at what time'.

| a. | * | Hoe laat | heeft | hij | naar zijn leraar | geluisterd? | activity |

| how late | has | he | to his teacher | listened |

| b. | Hoe laat | heeft | hij | zijn maaltijd | opgegeten? | accomplishment | |

| how late | has | he | his meal | prt.-eaten | |||

| 'At what time did he eat his meal?' | |||||||

| c. | * | Hoe laat | heeft | hij | van spinazie | gehouden? | state |

| how late | has | he | of spinach | liked |

| d. | Hoe laat | is | de bom | ontploft? | achievement | |

| how late | has | the bomb | exploded | |||

| 'At what time did the bomb explode?' | ||||||

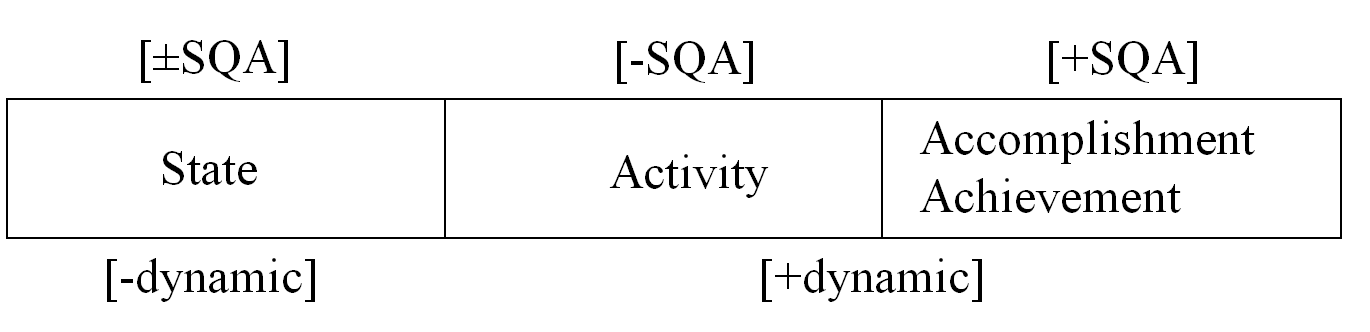

Distribution patterns like these suggest that the four verb classes can be defined by means of a binary feature system of the form in Table 4, in which the features ±bounded and ±continuous tense can be construed as given in Figure 3; cf. Verkuyl (1993).

| –bounded | +bounded | |

| –continuous tense | states | achievements |

| +continuous tense | activities | accomplishments |

Note that the feature ±bounded correlates with other semantic properties of the events. Accomplishments like opeten'to eat up' and achievements like ontploffen'to explode' in (72) both indicate that some participant in the event (here, respectively, the object and the subject) undergoes a change of state and that obtaining the new state marks the end of the event; the only difference is that the transformation requires some time in the former but is perceived as taking place instantaneously in the latter case.

| a. | Jan | at | de boterham | op. | accomplishment | |

| Jan | ate | the sandwich | prt. | |||

| 'Jan ate the sandwich.' | ||||||

| b. | De bom | ontploft. | achievement | |

| the bomb | explodes |

Activities and states, on the other hand, typically do not involve a change of stage and refer to more or less homogenous states of affairs with the result that the end of these states of affairs is more or less arbitrarily determined. This shows that it is not a priori clear whether the feature ±bounded is the correct feature; it might just as well have been ±change of state, as shown in Table 5. It therefore does not come as a surprise that there are a variety of binary feature systems available; see Rosen (2003: Section 1.3) for a brief discussion of some other proposals.

| –change of state | +change of state | |

| –continuous tense | states | achievements |

| +continuous tense | activities | accomplishments |

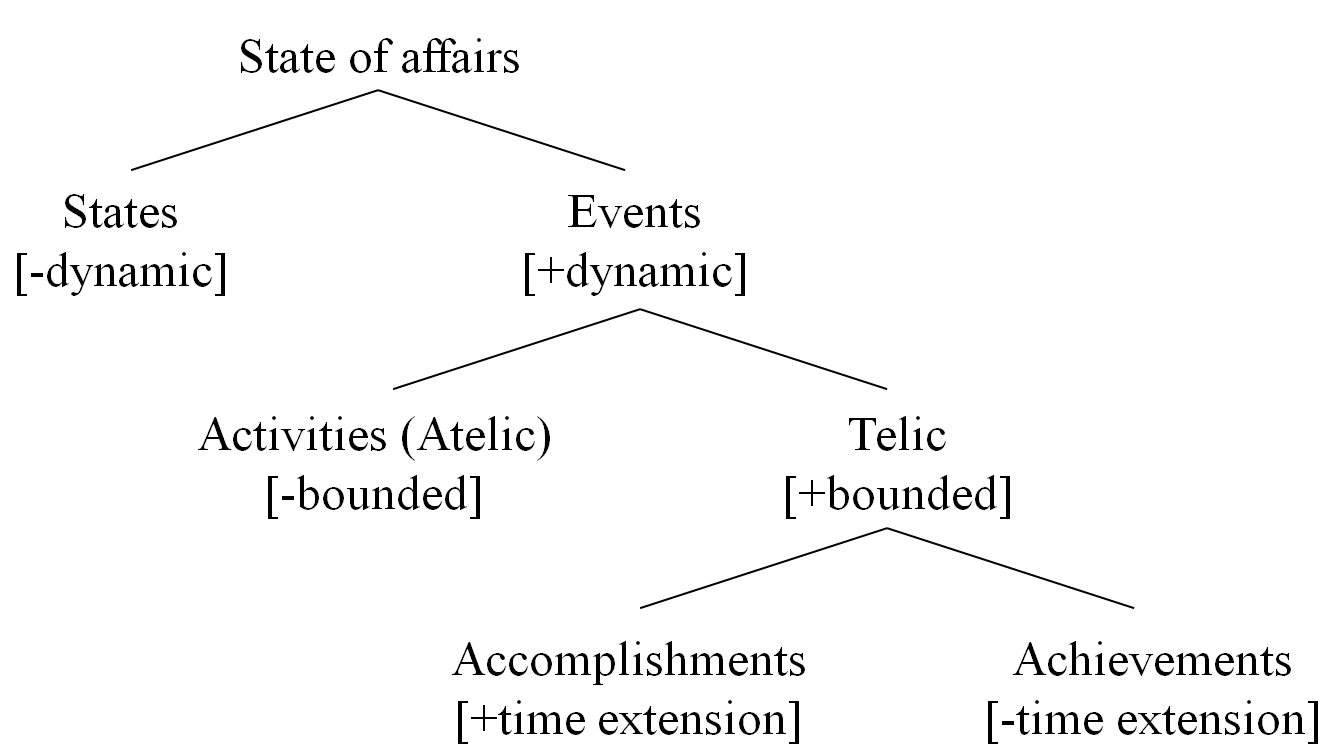

Other alternatives to Vendler's classification readily come to mind. Figure 4, which is based on Smith (1991) and Dik (1997), takes the basic division to be that between states and events: states lack internal dynamism in that they do not require any input of energy as nothing changes while they hold (Lehmann 1999:44), while events do have some form of internal dynamism. Events can be divided further on the basis of their boundedness: activities are not inherently bounded, whereas accomplishments and achievements are. The latter two differ in that only the former evolve over time. This gives rise to the hierarchical or at least more layered classification in Figure 4.

As this is not the place to discuss the pros and cons of the available feature systems, we will confine ourselves to summarizing some of the conspicuous properties of the verb classes as distinguished by Vendler (1957) by means of the table in (73); we refer the reader to Miller (1999) and Rosen (2003) for more discussion.

| state | activity | accomplishment | achievement | |

| dynamic | — | + | + | + |

| bounded/change-of-state | — | — | + | + |

| punctual | — | — | — | + |

| continuous tense | — | + | + | — |

This subsection discusses alternative approaches to Vendler's classification that do not primarily appeal to the internal temporal organization of the events, but instead to specific properties of the participants in the event. One example of this was already discussed in Subsection I, where it was observed that the aspectual feature ±bounded can readily be replaced by the feature ±change of state, which involves a property of one of the participants in the event. This shift in perspective may have been (unintentionally) initiated by Dowty (1979), who suggested (in line with the basic principle of Generative Semantics) that verbs can be semantically decomposed by means of a number of atomic semantic elements like do, become and cause, which combine with a stative n-place predicate πn in (74a) to form the more complex events in (74b-d), and, in fact, a number of more complex subclasses of these event types such as inchoative achievements like ontbranden'to ignite', which would be assigned the structure become [do (α1, [πn(α1, ..., αn)])].

| a. | State: πn(α1, ..., αn) |

| b. | Activity: do (α1, [πn(α1, ..., αn)]) |

| c. | Achievement: become [πn(α1, ..., αn)] |

| d. | Accomplishment: Φ cause (become [πn(α1, ..., αn)]) |

The status of the three semantic atoms is quite complex. The element do seems to function as a simple two-place predicate taking an argument of the stative predicate πn as well as the stative predicate itself as arguments. The element become, on the other hand, functions as an operator expressing that the truth value of the stative predicate πn(α1, ..., αn) changes from false to true. The element cause, finally, is a connective that expresses that event Φ is a causal factor for the event expressed by the formula following it (here: the achievement become [πn(α1, ..., αn)]); there is some event that causes some other event to come into existence.

The semantic structure attributed to accomplishments in (74d) correctly accounts for our intuition about example (75a) that the referent of the noun phrase het documenten'the documents' undergoes a change of state as the result of some unspecified action performed by the referent of the subject of the sentence, which may be further clarified by adding an instrumental met-PP like met een papierversnipperaar'with a paper shredder'; Jan has destroyed the documents by putting them in a shredder. It should be noted, however, that it is not immediately clear whether the inference that Jan is involved in some action is part of the meaning of the verb or the result of some conversational implicature in the sense of Grice (1975). The answer to this question depends on whether an example such as (75b) likewise expresses that there is some event that involves the referent of the noun phrase de orkaan'the hurricane' that causes a change of state in the referent of the noun phrase de stad'the city'.

| a. | Jan vernietigde | de documenten | (met een papierversnipperaar). | |

| Jan destroyed | the documents | with a paper shredder |

| b. | De | orkaan | vernietigde | de stad | (*met ....). | |

| the | hurricane | destroyed | the city | with |

The fact that it is not possible to add an instrumental met-PP to example (75b) suggests that the causal relation is more direct in this case and, consequently, that the inference we can draw from (75a) that it is some action of Jan that triggers the change of state is nothing more than a conversational implicature. Given this conclusion, it is tempting to simplify Dowty's semantic structures in (74) by construing all semantic atoms as n-place predicates, as in (76).

| a. | State: πn(α1, ..., αn) |

| b. | Activity: do(α1, [πn(α1, ..., αn)]) |

| c. | Achievement: become(β, [πn(α1, ..., αn)]], where β ∈ {α1, ..., αn} |

| d. | Accomplishment: cause(γ, (become (β, [πn(α1, ..., αn)])), in which β ∈ {α1, ..., αn} and γ ∉ { α1, ..., αn} |

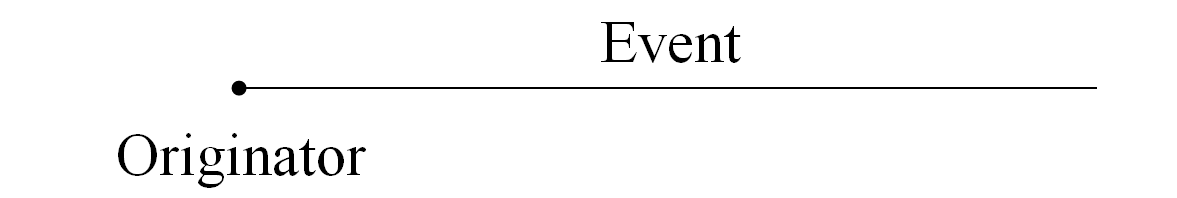

The interpretations of states and activities remain the same, but those of achievements and accomplishments change: an achievement is now interpreted as a change of state, such that β becomes an argument of πn, and an accomplishment is now interpreted as a change of state, such that β becomes an argument of πn as the result of some external cause γ. This reinterpretation of Dowty's system in fact seems to come very close to the proposals of the kind proposed in Van Voorst (1988) and Tenny (1994), who claim that Vendler's classes can be defined as in (77) by assuming that the nominal arguments in the clause may function as originator (typically the external argument) or delimiter (typically an internal argument of the verb) of the event; note that states do not fall in this classification since they are characterized by the absence of event structure; see also Levin & Rappaport Hovav (1995), Van Hout (1996), Van der Putten (1997) and many others for proposals in a similar spirit, and Levin & Rappaport Hovav (2005) for a recent review of research in this line of investigation.

| Activity: |  |

| Achievement: |  |

| Accomplishment: |  |

An advantage of taking participant roles as the basis of the aspectual classification of events is that this immediately accounts for the fact that the intransitive and transitive uses of verbs like schrijven'to write' and eten'to eat' differ in interpretation in the way they do: only the transitive primed examples have an internal argument that may function as delimiter.

| a. | Jan schreef | twee uur lang/*binnen twee uur. | activity | |

| Jan wrote | for two hours/within two hours |

| a'. | Jan schreef | de brief | binnen twee uur/*twee uur lang. | accomplishment | |

| Jan wrote | the letter | within two hours/for two hours |

| b. | Jan at | vijf minuten lang/*binnen vijf minuten. | activity | |

| Jan ate | for five minutes/within five minutes |

| b'. | Jan at | zijn lunch | binnen vijf minuten/*vijf minuten lang. | accomplishment | |

| Jan ate | his lunch | within five minutes/for five minutes |

Furthermore, this approach may provide a better understanding of the fact established earlier that properties of the nominal arguments of the verb may effect the aspectual interpretation by postulating additional conditions that the nominal arguments must meet in order to be able to function as delimiters; cf. the discussion of the examples in (64), repeated here as (79), which show that verbs like schrijven'to write' or eten'to eat' are only interpreted as accomplishments if the objects refer to specified quantities. This suggests that bare plurals and noun phrases headed by a mass noun cannot function as delimiters.

| a. | Jan schreef | gedurende/*binnen | twee jaar | boeken. | activity | |

| Jan wrote | during/within | two year | books |

| a'. | Jan schreef | binnen/*gedurende | twee jaar | drie boeken. | accomplishment | |

| Jan wrote | within/during | two year | three books |

| b. | Jan at | spaghetti. | activity | |

| Jan ate | spaghetti |

| b'. | Jan at | een bord spaghetti. | accomplishment | |

| Jan ate | a plate [of] spaghetti |

In fact, we can now also account for the fact illustrated in (65), repeated here as (80), that the subject may affect that the aspectual interpretation of the sentence by placing a similar restriction on the originator.

| a. | De bom | ontplofte | om drie uur/*de hele dag. | achievement | |

| the bomb | exploded | at three oʼclock/the whole day |

| b. | De bommen | ontploften | om drie uur/de hele dag. | achievement or activity | |

| the bombs | exploded | at three oʼclock/the whole day |

| c. | Er | ontploften | de hele dag/??om drie uur | bommen. | activity | |

| there | exploded | the whole day/at three oʼclock | bombs | |||

| 'There were bombs exploding the whole day.' | ||||||

This is formalized by Verkuyl (1972/2005) in his claim that the aspectual interpretation is compositional in the sense that it depends both on a feature of the verb and a feature of its nominal arguments (subject and object). According to Verkuyl the relevant feature of the verb is ±dynamic, which distinguishes between states and events, and the relevant feature of the nominal arguments is ±sqa, which distinguishes between noun phrases that refer to a specified quantity or a non-specified quantity; as soon as the subject or the object is assigned the feature -sqa the event becomes unbounded.

Another advantage of taking participant roles as the basis of the aspectual event classification is that we can also readily account for the fact that the so-called causative alternation in (81) has the effect of changing an achievement into an accomplishment: the causative construction in (81b) has an additional external argument that may act as originator.

| a. | Het raam | breekt. | achievement | |

| the window | breaks |

| b. | Jan breekt het raam. | accomplishment | |

| Jan breaks the window |

We can now also account for the earlier observation that the addition of complementives or verbal particles may affect the aspectual interpretation, by assuming that these add a meaning aspect to the construction which enables the object to function as a delimiter. Tenny (1994), for example, claims that such elements add a terminus (point of termination), as a result of which the object of an activity may become a delimiter; see the examples in (82).

| a. | Janoriginator | hielp | de dame. | activity | |

| Jan | helped | the lady |

| a'. | Janoriginator | hielp | de damedelimiter | uit de autoterminus. | accomplishment | |

| Jan | helped | the dame | out.of the car |

| b. | Janoriginator | duwde | de kar. | activity | |

| Jan | pushed | the cart |

| b'. | Janoriginator | duwde | de kardelimiter | wegterminus. | accomplishment | |

| Jan | pushed | the cart | away |

Something similar is shown by the slightly more complex cases in (66), repeated here as (83), in which the addition of a complementive/verbal particle adds a terminus and thus turns an intransitive activity into an (unaccusative) achievement.

| a. | Jan wandelde | twee uur lang/*binnen twee uur. | activity | |

| Jan walked | two hours long/within two hours | |||

| 'Jan walked for two hours.' | ||||

| b. | Jan wandelde | binnen twee uur/*twee uur lang | naar huis. | achievement | |

| Jan walked | within two hours/two hours long | to home | |||

| 'Jan walked home within two hours.' | |||||

| b'. | Jan wandelde | in twee uur/*twee uur lang | terug. | achievement | |

| Jan walked | in two hours/two hours long | back | |||

| 'Jan walked back within two hours.' | |||||

Note in passing that the (b)-examples were considered accomplishments under Vendler's approach because they are temporally bounded, but as achievements under the classification in (77) because Jan does not function as an originator but as a delimiter. This shows that the redefinition of Vendler's original categories in terms of participant roles is not innocuous, but may give rise to different dividing lines between event types.

The participant perspective on the aspectual classification of events discussed in Subsection II implies that temporal notions no longer enter this classification, subsection A will argue that this is a desirable result by showing that the feature ±time extension applies across all event types, and can thus be used to extend the classification, subsection B will discuss yet another feature, ±control, which has been argued to apply across all types of states of affairs and can likewise be used to extend the classification.

Subsection II has shown that Vendler's classification can be expressed by appealing to the roles that the nominal arguments play in the event and discussed a number of advantages of this shift of perspective. Another potential advantage is that activities, achievements and accomplishments are no longer defined by the temporal feature ±time extension. This enables us to solve the problem for Vendler's original proposal that there is a class of achievements that have temporal extension: verbs like afkoelen'cool', smelten'to melt' and zinken'to sink' are not momentaneous but involve a gradual change of state; cf. Dowty (1979: Section 2.3.5). Furthermore, we can now also define so-called semelfactive verbs like kloppen'to knock', krabben'to scratch' and kuchen'to cough' as instantaneous activities. Finally, we can also understand that accomplishments like een boek schrijven'to write a book' and een raam breken'to break a window' differ in their temporal extension. In short, the aspectual feature ±time extension can be used to divide all three main event types into two subclasses.

| [-time extension] | [+time extension] | |

| activities | kloppen 'to knock' kuchen 'to cough' knipogen 'to wink' rukken 'to jerk' | dragen 'to carry' lachen 'to laugh' luisteren 'to listen' wachten (op) 'to wait (for)' |

| achievements | aankomen 'to arrive' herkennen 'to recognize' ontploffen 'to explode' overlijden 'to die' | afkoelen 'to cool' smelten 'to melt' verdorren 'to wither' zinken 'to sink' |

| accomplishments | doorslikken 'to swallow' omstoten 'to knock over' verraden 'to betray' wegslaan 'to hit away' | bouwen 'to build' opeten 'to eat up' oversteken 'to cross' verbergen 'to hide' |

Note that our discussion above has abstracted away from the fact that properties of the nominal arguments of the verb may affect the temporal interpretation: crossing a square, for example, will have a temporal extension while crossing a line is instead instantaneous. The three classes of non-momentaneous verbs in Table (84) can easily be recognized, as they can always be the complement of the inchoative verb beginnen'to begin'.

| a. | Jan begon | te lachen. | activity | |

| Jan started | to laugh |

| b. | Het ijs | begon | te smelten. | achievement | |

| the ice | started | to melt |

| c. | Jan begon | het huis | te bouwen. | accomplishment | |

| Jan started | the house | to build | |||

| 'Jan started to build the house.' | |||||

The momentaneous verbs, on the other hand, normally do not allow this, except when they can be repeated and thus receive an iterative reading when combined with a durative adverbial phrase; cf. the examples in (86).

| a. | Jan kuchte | drie keer. | |

| Jan coughed | three times |

| a'. | Jan kuchte | vijf minuten lang. | |

| Jan coughed | for five minutes |

| b. | Jan sloeg | de hond | drie keer. | |

| Jan hit | the dog | three times |

| b'. | Jan sloeg | de hond | vijf minuten lang. | |

| Jan hit | the dog | for five minutes |

Since momentaneous activities differ from momentaneous achievements and accomplishments in that they can typically be repeated, it is the former but not the latter that are typically used as the complement of beginnen.

| a. | Jan begon | te kuchen. | |

| Jan started | to cough |

| b. | * | Jan begon | aan | te komen. |

| Jan started | prt. | to arrive |

| c. | * | Jan begon | de lamp | om | te stoten. |

| Jan started | the lamp | prt. | to knock.over |

Another way of extending Vendler's classification is by adding Dik's (1997) feature ±control. This feature denotes a property of the subject of the clause and expresses whether the referent of the subject is able to bring about or to terminate the event. The examples in (88) show that this feature can be superimposed on all four subclasses; the states of affairs in the primeless examples are all controlled, whereas those in the primed examples are not.

| a. | Jan gelooft | het. | |

| Jan believes | it |

| a'. | Jan weet het. | state | |

| Jan knows it |

| b. | Jan wandelt | in het park. | |

| Jan walks | in the park |

| b'. | Jan rilt | van de kou. | activity | |

| the shivers | from the cold |

| c. | Jan vertrok | op tijd. | |

| Jan left | in time |

| c'. | Jan overleed. | achievement | |

| Jan died |

| d. | Jan vernielde | de auto. | |

| Jan vandalized | the car |

| d'. | Jan verzwikte | zijn enkel. | accomplishment | |

| Jan twisted | his ankle |

Dik provides a number of tests that can be used to determine whether the subject is able to control the event. The first involves the use of the imperative: whereas controlled events allow the imperative, non-controlled events do not.

| a. | Geloof | het | maar! | |

| believe | it | prt. |

| a'. | * | Weet het maar! | state |

| Jan knows it |

| b. | Wandel | in het park! | |

| Jan walks | in the park |

| b'. | * | Ril van de kou! | activity |

| Shiver from the cold |

| c. | Vertrek | op tijd! | |

| leave | in time |

| c'. | * | overlijd! | achievement |

| die |

| d. | Verniel de auto! | |

| vandalize the car |

| d'. | * | Verzwik je enkel! | accomplishment |

| twist you ankle |

This finding is interesting because Vendler (1957) and Dowty (1979) have claimed that states cannot occur in the imperative form on their prototypical use: an example such as Ken uw rechten!'Know your rights!' was explained by claiming that this example did not involve an order/advice to know something, but to do something that would lead to the state of knowing something. Similarly, a command like Zit!'Sit!' would be interpreted as an instruction to perform some activity that would lead to assuming the desired posture. However, if geloven'to believe' indeed denotes a state, this cannot be maintained. Other typical states that can occur in the imperative are copular constructions, provided that the predicative element is a stage-level predicate, that is, a predicate that denotes a transitory property; individual-level predicates, that is, predicates that denote more permanent properties, normally give an infelicitous result in the imperative construction.

| a. | Wees | verstandig/geduldig! | stage-level predicate | |

| be | sensible/patient |

| b. | * | Wees | intelligent/klein! | individual-level predicate |

| be | intelligent/little |

Another context in which the difference between controlled and non-controlled events comes out clearly is in infinitival constructions such as (91), in which the implied subject PRO of the infinitival clause is interpreted as coreferential with the subject of the main verb beloven'to promise'.

| a. | Jan belooft [PRO | het | te geloven/*weten]. | |

| Jan promises | it | to believe/know | ||

| 'Jan promises to believe it.' | ||||

| b. | Jan belooft [PRO | te wandelen in het park/*te rillen van de kou]. | |

| Jan promises | to walk in the park/to shiver from the cold | ||

| 'Jan promises to walk in the park.' | |||

| c. | Jan belooft [PRO | op tijd | te vertrekken/*te overlijden]. | |

| Jan promises | in time | to leave/to die | ||

| 'Jan promises to leave in time.' | ||||

| d. | Jan beloofde [PRO | de auto | te vernielen/*zijn enkel | te verzwikken]. | |

| Jan promised | the car | to vandalize/his ankle | to twist | ||

| 'Jan promised to vandalize the car.' | |||||

Note that this again goes against earlier claims (e.g. Dowty 1979) that states cannot occur in this environment. The examples in (92) show that the difference between stage- and individual-level predicates that we observed in the copular constructions in (90) is also relevant in this context.

| a. | Jan beloofde [PRO | verstandig/geduldig | te zijn]! | stage-level predicate | |

| Jan promised | sensible/patient/nice | to be |

| b. | * | Jan beloofde [PRO | intelligent/klein | te zijn]. | individual-level predicate |

| Jan promised | intelligent/little | to be |

Although some verbs may require a +control or -control subject, other verbs may be more permissive in this respect; a verb like rollen'to roll' in (93), for example, is compatible both with a +control and a -control subject. That the referent of Jan in (93a) but the referent of de steen'the stone' in (93b) does not, is clear from the fact that the adverbial phrases opzettelijk/vrijwillig'on purpose/voluntarily' can be used with the former only. The examples also show that +control subjects are typically animate (with the possible exception of certain machines).

| a. | Jan rolde | opzettelijk/vrijwillig | van de heuvel. | |

| Jan rolled | on purpose/voluntarily | from the hill |

| b. | De steen | rolde | (*opzettelijk/*vrijwillig) | van de heuvel. | |

| the stone | rolled | on purpose/voluntarily | from the hill |

Note in passing that notions like controllability or volitionality are often seen as defining properties of the thematic role of agent; cf. the discussion in Levin & Rappaport Hovav (2005: Section 2.3.1). The fact that the subjects of states and achievements, which are normally not assigned the role of agent, can also have this property and the fact that the interpretation of the event may depend on the animacy of the subject casts some doubt on proposals of this sort.

The previous subsections reviewed one line of research concerned with verb/event classification that started with Vendler (1957), but there are other classifications based on specific inherent conceptual properties of verbs. Verbs have been classified as, for instance, verbs of putting, removing, sending and carrying, change of possession, concealment, creation and transformation, perception, social interaction, communication, sound and light emission, bodily functions, grooming and bodily care, and so on; see Levin (1993: Part II) for a long list of such classes. Although lists like these may seem somewhat arbitrary, making such distinctions can be useful, as these classes may exhibit several defining semantic and syntactic properties; Levin's classification, for instance, is based on the ways in which the participants involved in the state of affairs can be syntactically expressed in English. Although we will refer to at least some of these classes in our discussion of verb frame alternations in Chapter 3, we do not think it would be very helpful or insightful to list them here: we will introduce the relevant classes where needed and refer the reader to Levin's reference book for details.

- 2010Construction morphologynullnullOxford/New YorkOxford University Press

- 1997The theory of functional grammar, Part 1: the structure of the clausenullnullnullMouton de Gruyter

- 1997The theory of functional grammar, Part 1: the structure of the clausenullnullnullMouton de Gruyter

- 1997The theory of functional grammar, Part 1: the structure of the clausenullnullnullMouton de Gruyter

- 1979Word meaning in Montague grammar. The semantics of verbs and times in Generative Semantics and in Montague's PTQnullnullDordrechtReidel

- 1979Word meaning in Montague grammar. The semantics of verbs and times in Generative Semantics and in Montague's PTQnullnullDordrechtReidel

- 1979Word meaning in Montague grammar. The semantics of verbs and times in Generative Semantics and in Montague's PTQnullnullDordrechtReidel

- 1979Toward a semantic analysis of verb aspect and the English imperfective progressiveLanguage and Philosophy145-77

- 1979Word meaning in Montague grammar. The semantics of verbs and times in Generative Semantics and in Montague's PTQnullnullDordrechtReidel

- 1979Word meaning in Montague grammar. The semantics of verbs and times in Generative Semantics and in Montague's PTQnullnullDordrechtReidel

- 1979Word meaning in Montague grammar. The semantics of verbs and times in Generative Semantics and in Montague's PTQnullnullDordrechtReidel

- 1975Logic and conversationCole, P. & Morgan, J. (eds.)Speech acts: Syntax and Semantics 3New YorkAcademic Press41-58

- 1996Event semantics of verb frame alternations: a case study of Dutch and its acquisitionTilburgTilburg UniversityThesis

- 1999Aspectual type(s)Brown, Keith & Miller, Jim (eds.)Concise encyclopedia of grammatical categoriesOxfordElsevier43-49

- 1999Aspectual type(s)Brown, Keith & Miller, Jim (eds.)Concise encyclopedia of grammatical categoriesOxfordElsevier43-49

- 1993English verb classes and alternationsnullnullChicago/LondonUniversity of Chicago Press

- 1995Unaccusativity at the syntax-lexical semantics interfacenullnullCambridge, MA/LondonMIT Press

- 2005Argument realizationnullnullCambridge/New YorkCambridge University Press

- 2005Argument realizationnullnullCambridge/New YorkCambridge University Press

- 1999Aspect: Further developmentsBrown, Keith & Miller, Jim (eds.)Concise encyclopedia of grammatical categoriesOxfordElsevier43-49

- 1997Mind and matter in morphology. Syntactic and lexical deverbal morphology in DutchLeidenUniversity of LeidenThesis

- 2003The syntactic representation of linguistic eventsCheng, Lisa & Sybesma. Rint (eds.)The second <i>Glot International</i> State-of-the-Article book. The latest in LinguisticsBerlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter323-367

- 2003The syntactic representation of linguistic eventsCheng, Lisa & Sybesma. Rint (eds.)The second <i>Glot International</i> State-of-the-Article book. The latest in LinguisticsBerlin/New YorkMouton de Gruyter323-367

- 1991The parameter of aspectnullnullDordrechtKluwer Academic Publishers

- 1994Aspectual roles and the syntax-semantics interfacenullnullDordrechtKluwer

- 1994Aspectual roles and the syntax-semantics interfacenullnullDordrechtKluwer

- 1957Verbs and timesThe Philosophical Review56143-160

- 1957Verbs and timesThe Philosophical Review56143-160

- 1957Verbs and timesThe Philosophical Review56143-160

- 1957Verbs and timesThe Philosophical Review56143-160

- 1957Verbs and timesThe Philosophical Review56143-160

- 1957Verbs and timesThe Philosophical Review56143-160

- 1957Verbs and timesThe Philosophical Review56143-160

- 1957Verbs and timesThe Philosophical Review56143-160

- 1972On the compositional nature of the aspectsnullnullDordrechtReidel

- 1972On the compositional nature of the aspectsnullnullDordrechtReidel

- 1972On the compositional nature of the aspectsnullnullDordrechtReidel

- 1993A theory of aspectuality. The interaction between temporal and atemporal structurenullnullCambridgeCambridge University Press

- 1993A theory of aspectuality. The interaction between temporal and atemporal structurenullnullCambridgeCambridge University Press

- 2005Aspectual composition: surveying the ingredientsVerkuyl, Henk J., Swart, Henriëtte de & Hout, Angeliek van (eds.)Perspectives on aspectDordrechtSpringer19-39

- 2005Aspectual composition: surveying the ingredientsVerkuyl, Henk J., Swart, Henriëtte de & Hout, Angeliek van (eds.)Perspectives on aspectDordrechtSpringer19-39

- 1988Event structurenullnullAmsterdam/PhiladelphiaJohn Benjamins