- Dutch

- Frisian

- Saterfrisian

- Afrikaans

-

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological processes

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Word stress

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Monomorphemic words

- Diachronic aspects

- Generalizations on stress placement

- Default penultimate stress

- Lexical stress

- The closed penult restriction

- Final closed syllables

- The diphthong restriction

- Superheavy syllables (SHS)

- The three-syllable window

- Segmental restrictions

- Phonetic correlates

- Stress shifts in loanwords

- Quantity-sensitivity

- Secondary stress

- Vowel reduction in unstressed syllables

- Stress in complex words

- Primary stress in simplex words

- Accent & intonation

- Clitics

- Spelling

- Morphology

- Word formation

- Compounding

- Nominal compounds

- Verbal compounds

- Adjectival compounds

- Affixoids

- Coordinative compounds

- Synthetic compounds

- Reduplicative compounds

- Phrase-based compounds

- Elative compounds

- Exocentric compounds

- Linking elements

- Separable complex verbs (SCVs)

- Gapping of complex words

- Particle verbs

- Copulative compounds

- Derivation

- Numerals

- Derivation: inputs and input restrictions

- The meaning of affixes

- Non-native morphology

- Cohering and non-cohering affixes

- Prefixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixation: person nouns

- Conversion

- Pseudo-participles

- Bound forms

- Nouns

- Nominal prefixes

- Nominal suffixes

- -aal and -eel

- -aar

- -aard

- -aat

- -air

- -aris

- -ast

- Diminutives

- -dom

- -een

- -ees

- -el (nominal)

- -elaar

- -enis

- -er (nominal)

- -erd

- -erik

- -es

- -eur

- -euse

- ge...te

- -heid

- -iaan, -aan

- -ief

- -iek

- -ier

- -ier (French)

- -ière

- -iet

- -igheid

- -ij and allomorphs

- -ijn

- -in

- -ing

- -isme

- -ist

- -iteit

- -ling

- -oir

- -oot

- -rice

- -schap

- -schap (de)

- -schap (het)

- -sel

- -st

- -ster

- -t

- -tal

- -te

- -voud

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Adverbs

- Univerbation

- Neo-classical word formation

- Construction-dependent morphology

- Morphological productivity

- Compounding

- Inflection

- Inflection and derivation

- Allomorphy

- The interface between phonology and morphology

- Word formation

- Syntax

- Preface and acknowledgements

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of verb phrases I:Argument structure

- 3 Projection of verb phrases II:Verb frame alternations

- Introduction

- 3.1. Main types

- 3.2. Alternations involving the external argument

- 3.3. Alternations of noun phrases and PPs

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.3.1.1. Dative alternation with aan-phrases (recipients)

- 3.3.1.2. Dative alternation with naar-phrases (goals)

- 3.3.1.3. Dative alternation with van-phrases (sources)

- 3.3.1.4. Dative alternation with bij-phrases (possessors)

- 3.3.1.5. Dative alternation with voor-phrases (benefactives)

- 3.3.1.6. Conclusion

- 3.3.1.7. Bibliographical notes

- 3.3.2. Accusative/PP alternations

- 3.3.3. Nominative/PP alternations

- 3.3.1. Dative/PP alternations (dative shift)

- 3.4. Some apparent cases of verb frame alternation

- 3.5. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of verb phrases IIIa:Selection of clauses/verb phrases

- 5 Projection of verb phrases IIIb:Argument and complementive clauses

- Introduction

- 5.1. Finite argument clauses

- 5.2. Infinitival argument clauses

- 5.3. Complementive clauses

- 6 Projection of verb phrases IIIc:Complements of non-main verbs

- 7 Projection of verb phrases IIId:Verb clusters

- 8 Projection of verb phrases IV: Adverbial modification

- 9 Word order in the clause I:General introduction

- 10 Word order in the clause II:Position of the finite verb (verb-first/second)

- 11 Word order in the clause III:Clause-initial position (wh-movement)

- Introduction

- 11.1. The formation of V1- and V2-clauses

- 11.2. Clause-initial position remains (phonetically) empty

- 11.3. Clause-initial position is filled

- 12 Word order in the clause IV:Postverbal field (extraposition)

- 13 Word order in the clause V: Middle field (scrambling)

- 14 Main-clause external elements

- Nouns and Noun Phrases

- 1 Characterization and classification

- 2 Projection of noun phrases I: complementation

- Introduction

- 2.1. General observations

- 2.2. Prepositional and nominal complements

- 2.3. Clausal complements

- 2.4. Bibliographical notes

- 3 Projection of noun phrases II: modification

- Introduction

- 3.1. Restrictive and non-restrictive modifiers

- 3.2. Premodification

- 3.3. Postmodification

- 3.3.1. Adpositional phrases

- 3.3.2. Relative clauses

- 3.3.3. Infinitival clauses

- 3.3.4. A special case: clauses referring to a proposition

- 3.3.5. Adjectival phrases

- 3.3.6. Adverbial postmodification

- 3.4. Bibliographical notes

- 4 Projection of noun phrases III: binominal constructions

- Introduction

- 4.1. Binominal constructions without a preposition

- 4.2. Binominal constructions with a preposition

- 4.3. Bibliographical notes

- 5 Determiners: articles and pronouns

- Introduction

- 5.1. Articles

- 5.2. Pronouns

- 5.3. Bibliographical notes

- 6 Numerals and quantifiers

- 7 Pre-determiners

- Introduction

- 7.1. The universal quantifier al 'all' and its alternants

- 7.2. The pre-determiner heel 'all/whole'

- 7.3. A note on focus particles

- 7.4. Bibliographical notes

- 8 Syntactic uses of noun phrases

- Adjectives and Adjective Phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- 2 Projection of adjective phrases I: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adjective phrases II: Modification

- 4 Projection of adjective phrases III: Comparison

- 5 Attributive use of the adjective phrase

- 6 Predicative use of the adjective phrase

- 7 The partitive genitive construction

- 8 Adverbial use of the adjective phrase

- 9 Participles and infinitives: their adjectival use

- 10 Special constructions

- Adpositions and adpositional phrases

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Introduction

- 1.1. Characterization of the category adposition

- 1.2. A formal classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3. A semantic classification of adpositional phrases

- 1.3.1. Spatial adpositions

- 1.3.2. Temporal adpositions

- 1.3.3. Non-spatial/temporal prepositions

- 1.4. Borderline cases

- 1.5. Bibliographical notes

- 2 Projection of adpositional phrases: Complementation

- 3 Projection of adpositional phrases: Modification

- 4 Syntactic uses of the adpositional phrase

- 5 R-pronominalization and R-words

- 1 Characteristics and classification

- Phonology

-

- General

- Phonology

- Segment inventory

- Phonotactics

- Phonological Processes

- Assimilation

- Vowel nasalization

- Syllabic sonorants

- Final devoicing

- Fake geminates

- Vowel hiatus resolution

- Vowel reduction introduction

- Schwa deletion

- Schwa insertion

- /r/-deletion

- d-insertion

- {s/z}-insertion

- t-deletion

- Intrusive stop formation

- Breaking

- Vowel shortening

- h-deletion

- Replacement of the glide w

- Word stress

- Clitics

- Allomorphy

- Orthography of Frisian

- Morphology

- Inflection

- Word formation

- Derivation

- Prefixation

- Infixation

- Suffixation

- Nominal suffixes

- Verbal suffixes

- Adjectival suffixes

- Adverbial suffixes

- Numeral suffixes

- Interjectional suffixes

- Onomastic suffixes

- Conversion

- Compositions

- Derivation

- Syntax

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Unergative and unaccusative subjects

- Evidentiality

- To-infinitival clauses

- Predication and noun incorporation

- Ellipsis

- Imperativus-pro-Infinitivo

- Expression of irrealis

- Embedded Verb Second

- Agreement

- Negation

- Nouns & Noun Phrases

- Classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Partitive noun constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Nominalised quantifiers

- Kind partitives

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Bare nominal attributions

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers and (pre)determiners

- Interrogative pronouns

- R-pronouns

- Syntactic uses

- Adjective Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification and degree quantification

- Comparison by degree

- Comparative

- Superlative

- Equative

- Attribution

- Agreement

- Attributive adjectives vs. prenominal elements

- Complex adjectives

- Noun ellipsis

- Co-occurring adjectives

- Predication

- Partitive adjective constructions

- Adverbial use

- Participles and infinitives

- Adposition Phrases

- Characteristics and classification

- Complementation

- Modification

- Intransitive adpositions

- Predication

- Preposition stranding

- Verbs and Verb Phrases

-

- General

- Morphology

- Morphology

- 1 Word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 1.1.1 Compounds and their heads

- 1.1.2 Special types of compounds

- 1.1.2.1 Affixoids

- 1.1.2.2 Coordinative compounds

- 1.1.2.3 Synthetic compounds and complex pseudo-participles

- 1.1.2.4 Reduplicative compounds

- 1.1.2.5 Phrase-based compounds

- 1.1.2.6 Elative compounds

- 1.1.2.7 Exocentric compounds

- 1.1.2.8 Linking elements

- 1.1.2.9 Separable Complex Verbs and Particle Verbs

- 1.1.2.10 Noun Incorporation Verbs

- 1.1.2.11 Gapping

- 1.2 Derivation

- 1.3 Minor patterns of word formation

- 1.1 Compounding

- 2 Inflection

- 1 Word formation

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

- 0 Introduction to the AP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of APs

- 2 Complementation of APs

- 3 Modification and degree quantification of APs

- 4 Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative

- 5 Attribution of APs

- 6 Predication of APs

- 7 The partitive adjective construction

- 8 Adverbial use of APs

- 9 Participles and infinitives as APs

- Nouns and Noun Phrases (NPs)

- 0 Introduction to the NP

- 1 Characteristics and Classification of NPs

- 2 Complementation of NPs

- 3 Modification of NPs

- 3.1 Modification of NP by Determiners and APs

- 3.2 Modification of NP by PP

- 3.3 Modification of NP by adverbial clauses

- 3.4 Modification of NP by possessors

- 3.5 Modification of NP by relative clauses

- 3.6 Modification of NP in a cleft construction

- 3.7 Free relative clauses and selected interrogative clauses

- 4 Partitive noun constructions and constructions related to them

- 4.1 The referential partitive construction

- 4.2 The partitive construction of abstract quantity

- 4.3 The numerical partitive construction

- 4.4 The partitive interrogative construction

- 4.5 Adjectival, nominal and nominalised partitive quantifiers

- 4.6 Kind partitives

- 4.7 Partitive predication with a preposition

- 4.8 Bare nominal attribution

- 5 Articles and names

- 6 Pronouns

- 7 Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- 8 Interrogative pronouns

- 9 R-pronouns and the indefinite expletive

- 10 Syntactic functions of Noun Phrases

- Adpositions and Adpositional Phrases (PPs)

- 0 Introduction to the PP

- 1 Characteristics and classification of PPs

- 2 Complementation of PPs

- 3 Modification of PPs

- 4 Bare (intransitive) adpositions

- 5 Predication of PPs

- 6 Form and distribution of adpositions with respect to staticity and construction type

- 7 Adpositional complements and adverbials

- Verbs and Verb Phrases (VPs)

- 0 Introduction to the VP in Saterland Frisian

- 1 Characteristics and classification of verbs

- 2 Unergative and unaccusative subjects and the auxiliary of the perfect

- 3 Evidentiality in relation to perception and epistemicity

- 4 Types of to-infinitival constituents

- 5 Predication

- 5.1 The auxiliary of being and its selection restrictions

- 5.2 The auxiliary of going and its selection restrictions

- 5.3 The auxiliary of continuation and its selection restrictions

- 5.4 The auxiliary of coming and its selection restrictions

- 5.5 Modal auxiliaries and their selection restrictions

- 5.6 Auxiliaries of body posture and aspect and their selection restrictions

- 5.7 Transitive verbs of predication

- 5.8 The auxiliary of doing used as a semantically empty finite auxiliary

- 5.9 Supplementive predication

- 6 The verbal paradigm, irregularity and suppletion

- 7 Verb Second and the word order in main and embedded clauses

- 8 Various aspects of clause structure

- Adjectives and adjective phrases (APs)

-

- General

- Phonology

- Afrikaans phonology

- Segment inventory

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- The diphthongised long vowels /e/, /ø/ and /o/

- The unrounded mid-front vowel /ɛ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /ɑ/

- The unrounded low-central vowel /a/

- The rounded mid-high back vowel /ɔ/

- The rounded high back vowel /u/

- The rounded and unrounded high front vowels /i/ and /y/

- The unrounded and rounded central vowels /ə/ and /œ/

- The diphthongs /əi/, /œy/ and /œu/

- Overview of Afrikaans consonants

- The bilabial plosives /p/ and /b/

- The alveolar plosives /t/ and /d/

- The velar plosives /k/ and /g/

- The bilabial nasal /m/

- The alveolar nasal /n/

- The velar nasal /ŋ/

- The trill /r/

- The lateral liquid /l/

- The alveolar fricative /s/

- The velar fricative /x/

- The labiodental fricatives /f/ and /v/

- The approximants /ɦ/, /j/ and /ʋ/

- Overview of Afrikaans vowels

- Word stress

- The phonetic properties of stress

- Primary stress on monomorphemic words in Afrikaans

- Background to primary stress in monomorphemes in Afrikaans

- Overview of the Main Stress Rule of Afrikaans

- The short vowels of Afrikaans

- Long vowels in monomorphemes

- Primary stress on diphthongs in monomorphemes

- Exceptions

- Stress shifts in place names

- Stress shift towards word-final position

- Stress pattern of reduplications

- Phonological processes

- Vowel related processes

- Consonant related processes

- Homorganic glide insertion

- Phonology-morphology interface

- Phonotactics

- Morphology

- Syntax

- Afrikaans syntax

- Nouns and noun phrases

- Characteristics of the NP

- Classification of nouns

- Complementation of NPs

- Modification of NPs

- Binominal and partitive constructions

- Referential partitive constructions

- Partitive measure nouns

- Numeral partitive constructions

- Partitive question constructions

- Partitive constructions with nominalised quantifiers

- Partitive predication with prepositions

- Binominal name constructions

- Binominal genitive constructions

- Bare nominal attribution

- Articles and names

- Pronouns

- Quantifiers, determiners and predeterminers

- Syntactic uses of the noun phrase

- Adjectives and adjective phrases

- Characteristics and classification of the AP

- Complementation of APs

- Modification and Degree Quantification of APs

- Comparison by comparative, superlative and equative degree

- Attribution of APs

- Predication of APs

- The partitive adjective construction

- Adverbial use of APs

- Participles and infinitives as adjectives

- Verbs and verb phrases

- Characterisation and classification

- Argument structure

- Verb frame alternations

- Complements of non-main verbs

- Verb clusters

- Complement clauses

- Adverbial modification

- Word order in the clause: Introduction

- Word order in the clause: position of the finite Verb

- Word order in the clause: Clause-initial position

- Word order in the clause: Extraposition and right-dislocation in the postverbal field

- Word order in the middle field

- Emphatic constructions

- Adpositions and adposition phrases

Verbs (V), nouns (N), adjectives (A) and prepositions (P) constitute the four major word classes. The present study deals with verbs and their projections (verb phrases). It is organized as follows.

- I. Characterization and classification (Chapter 1)

- II. Argument structures (Chapter 2)

- III. Verb frame alternations (Chapter 3)

- IV. Clausal/verbal complements (Chapter 4 to Chapter 7)

- V. Modification (Chapter 8)

- VI. Word Order (Chapter 9 to Chapter 13)

- VII. Clause-external elements (Chapter 14)

- VIII. Syntactic uses of verbal projections

Section 1.1 provides a brief survey of some conspicuous syntactic, morphological and semantic characteristics of verbs. Section 1.2 reviews a number of semantic and syntactic classifications of verbs and proposes a partly novel classification bringing together some of these proposals; this classification will be the starting point of the more extensive discussion of nominal complementation in Chapter 2. Section 1.3 discusses verbal inflection while Sections 1.4 and 1.5 discuss a number of semantic notions related to verbs: tense, mood/modality and aspect.

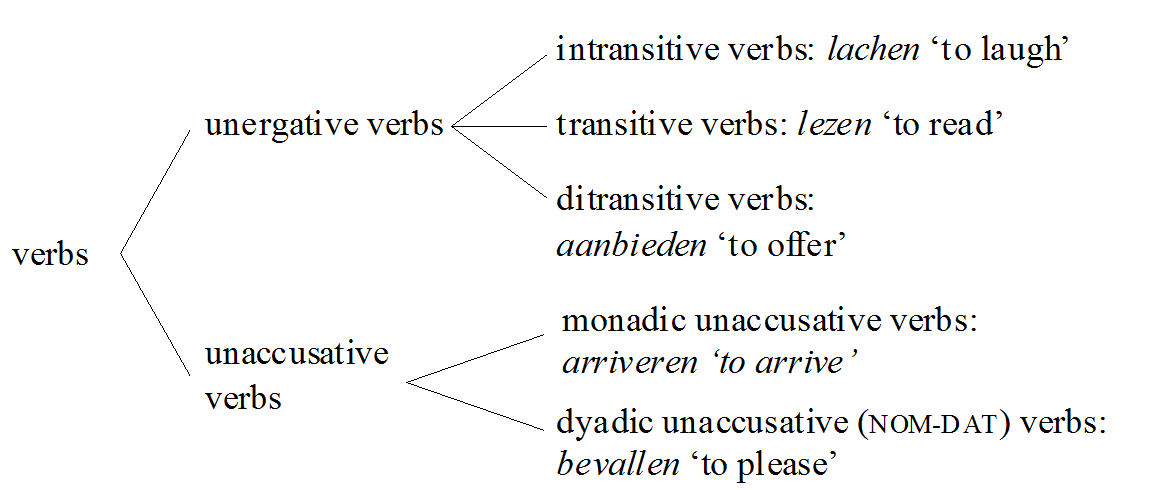

Verbs can project in the sense that they take arguments (Chapter 2 to Chapter 5) and that the resulting projections can be modified by a large set of adverbial phrases (Chapter 8). We will begin the discussion of complementation by focusing on the adicity of verbs, that is, the number and type of arguments they can take. The traditional classification is normally based on the number of nominal arguments that verbs take, that is, whether a verb is intransitive, transitive or ditransitive.

| a. | Jan lacht. | intransitive | |

| Jan laughs |

| b. | Jan leest een boek. | transitive | |

| Jan reads a book |

| c. | Jan biedt | Peter een baan | aan. | ditransitive | |

| Jan offers | Peter a job | prt. |

Chapter 2 provides evidence, however, that in order to arrive at a satisfactory classification not only the number but also the type of arguments should be taken into account: we have to distinguish between what have become known as unergative and unaccusative verbs, which exhibit systematic differences in syntactic behavior. Because the distinction is relatively new (it was first proposed in Perlmutter 1978, and has received wider recognition only after Burzio 1981/1986) but nevertheless plays an important role throughout this study, we will briefly introduce the distinction here.

Unaccusative verbs never take an accusative object. The subjects of these verbs maintain a similar semantic relation with the unaccusative verb as direct objects with transitive verbs; they are both assigned the thematic role of theme. This is illustrated by the minimal pair in (2); the nominative noun phrase het glas'the glass' in the unaccusative construction (2b) maintains the same relation with the verb as the accusative noun phrase het glas in the transitive construction in (2a). It is therefore generally assumed that the subject in (2b) originates in the regular direct object position, but is not assigned accusative case by the verb, so that it must be promoted to subject, for which reason we will call the subject of an unaccusative verb a DO-subject. The fact that (2b) has a transitive alternant is an incidental property of the verb breken'to break'. Some verbs, such as arriveren'to arrive', only occur in an unaccusative frame.

| a. | Jan | breekt het glas. | |

| Jan | breaks the glass |

| a'. | * | Jan arriveert | het boek. | transitive |

| Jan arrives | the book |

| b. | Het glas | breekt. | |

| the glass | breaks |

| b'. | Het boek | arriveert. | unaccusative | |

| the book | arrives |

Hoekstra (1984a) has argued that regular intransitive verbs and unaccusative verbs have three distinguishing properties: (a) intransitives take the perfect auxiliary hebben'to have', whereas unaccusatives take the auxiliary zijn'to be'; (b) the past/passive participle of unaccusatives can be used attributively to modify a head noun that corresponds to the subject of the verbal construction, whereas this is not possible with intransitive verbs; (c) the impersonal passive is possible with intransitive verbs only. These properties are illustrated in (3) by means of the intransitive verb lachen'to laugh' and the unaccusative arriveren'to arrive'.

| a. | Jan heeft/*is gelachen. | |

| Jan has/is laughed |

| b. | Jan is/*heeft gearriveerd. | |

| Jan is/has arrived |

| a'. | * | de gelachen jongen |

| the laughed boy |

| b'. | de gearriveerde jongen | |

| the arrived boy |

| a''. | Er werd gelachen. | |

| there was laughed |

| b''. | * | Er werd gearriveerd. |

| there was arrived |

Mulder & Wehrmann (1989), however, argued that only a subset of the unaccusative verbs exhibits all the properties in (3). Locational verbs like hangen in (4), for example, enter into a similar alternation as the verb breken in (2), but nevertheless the verb in (4b) does not fully exhibit the behavior of the verb arriveren, as is clear from the fact that it takes the auxiliary hebben in the perfect tense. It has been suggested that this might be due to the fact that there is an aspectual difference between the verbs arriveren and hangen: the former is telic whereas the latter is not.

| a. | Jan hangt | de jas | in de kast. | transitive | |

| Jan hangs | the coat | into the wardrobe |

| b. | De jas | hangt | in de kast. | intransitive | |

| the coat | hangs | in the wardrobe |

The examples in (5) show that we can make a similar distinction for the dyadic verbs. A verb like bevallen'to please' in the (b)-examples behaves like an unaccusative verb in the sense that it selects the auxiliary zijn and cannot be passivized. Since the object would appear with dative case in languages with morphological case (cf. the German verb gefallen'to please'), such verbs have become known as nominative-dative (nom-dat) verbs. A verb like onderzoeken'to examine' in the (a)-examples behaves like a traditional transitive verb in that it selects the auxiliary hebben and can be passivized while in a language with morphological case the object would be assigned accusative case (cf. the German verb besuchen'to visit').

| a. | De dokter | heeft/*is | Marie gisteren | onderzocht. | |

| the physician | has/*is | Marie yesterday | examined |

| a'. | Marie is | gisteren | (door de dokter) | onderzocht. | |

| Marie has.been | yesterday | by the physician | examined |

| b. | De nieuwe voorzitter | is/*heeft | mij | goed | bevallen. | |

| the new chairman | is/has | me | well | pleased |

| b'. | * | Ik | ben | goed | bevallen | (door de nieuwe voorzitter). |

| I | have.been | well | pleased | by the new chairman |

Given that unaccusative verbs have a DO-subject, that is, a subject that occupies an underlying object position, we correctly predict that unaccusative triadic verbs do not exist. Consequently, if the distinction between what is nowadays known as unergative (verbs that in principle can assign accusative case) and unaccusative verbs is indeed on the right track, we have to extend the traditional classification of verbs at least as in Figure 1. Sections 1.2 and 2.1 will argue that there are reasons to extend the classification in Figure 1 even further, but we will not digress on this here.

Section 2.2 discusses verbs taking various types of predicative complements. Examples are the copulas, the verb vinden'to consider' and a large set of verbs that may combine with a resultative phrase.

| a. | Jan is aardig. | copular construction | |

| Jan is nice |

| b. | Ik | vind | Jan aardig. | vinden-construction | |

| I | consider | Jan nice |

| c. | Jan slaat | Peter dood. | resultative construction | |

| Jan hits | Peter dead |

We will also show that verbs entering the resultative construction may shift from one verb class to another by (apparently) changing their adicity, as illustrated in the (a)-examples in (7), or their selectional properties, as in the (b)-examples.

| a. | Jan loopt | (*het gras). | adicity | |

| Jan walks | the grass |

| a'. | Jan loopt | *(het gras) | plat. | |

| Jan walks | the grass | flat |

| b. | Jan veegt | de vloer/$bezem. | selection | |

| Jan brushes | the floor/broom |

| b'. | Jan veegt | de bezem/$vloer | kapot. | |

| Jan brushes | the broom/floor | broken |

Sections 2.3 and 2.4 discuss verbs taking PP-complements, like wachten'to wait' in (8a). and the somewhat more special cases such as wegen'to weigh' in (8b) that take an obligatory adjectival phrase. The discussion of complements in the form of a clause will be postponed to Chapter 5.

| a. | Jan wacht op vader. | PP-complements | |

| Jan waits for father |

| b. | Jan weegt | veel te zwaar. | AP-complements | |

| Jan weighs | much too heavy |

Section 2.5 concludes by discussing another number of more special verb types like inherently reflexive verbs and so-called object experiencer verbs.

| a. | Jan vergist | zich. | inherently reflexive verb | |

| Jan be.mistaken | refl |

| b. | Die opmerking | irriteert | Jan/hem. | object experiencer verb | |

| that remark | annoys | Jan/him |

The previous subsection has already shown that it is not always possible to say that a specific verb categorically belongs to a single class: examples (2) and (4), for instance, demonstrate that the verbs breken'to break' and hangen'to hang' can be used both as a transitive and as an unaccusative verb. And the examples in (7) show that the class of the verb may apparently also depend on other elements in the clause. This phenomenon that verbs may be the head of more of one type of syntactic frame is known as verb frame alternation will be discussed in Chapter 3. Another familiar type of alternation, known as dative shift, is illustrated in (10).

| a. | Marie geeft | het boek | aan Peter. | dative shift | |

| Marie gives | the book | to Peter |

| b. | Marie geeft | Peter | het boek. | |

| Marie gives | Peter | the book |

We will take a broad view of the term verb frame alternation and include voice alternations such as the alternation between active and passive clauses, illustrated in the (a)-examples in (11), as well as alternations that are the result of derivational morphology, such as the so-called locative alternation in the (b)-examples in (11), which is triggered by the affixation by the prefix be-.

| a. | Jan leest | het boek. | passivization | |

| Jan reads | the book |

| a'. | Het boek | wordt | door Jan | gelezen. | |

| the book | is | by Jan | read |

| b. | Jan plakt | een foto | op zijn computer. | locative alternation | |

| Jan pastes | a picture | on his computer |

| b'. | Jan beplakt | zijn computer | met foto's. | |

| Jan be-pastes | his computer | with pictures |

These chapters in a sense continue the discussion in Chapter 2 on argument structure by discussing cases in which verbs take a verbal dependent, that is, a clause or a smaller (extended) projection of some other verb. The reason not to discuss this type of complementation in Chapter 2 is that it does not essentially alter the syntactic verb classification developed there: for example, many of the verbs taking an internal argument have the option of choosing between a nominal and a clausal complement. The reason for devoting a separate chapter to clausal/verbal arguments is that such arguments exhibit many special properties and introduce a number of complicating factors that have been investigated extensively in the literature. Even a brief discussion of these special properties and complicating factors would have seriously hampered the main line of argumentation in Chapter 2, and it is therefore better to discuss these properties in their own right.

Chapter 5 provides an exhaustive discussion of dependent clauses functioning as arguments or complementives. Section 5.1 starts with finite argument clauses; we will discuss subject, direct object, and prepositional clauses. This section also includes a discussion of fragment clauses and wh-extraction.

| a. | dat | duidelijk | is | [dat | Marie de nieuwe voorzitter | wordt]. | subject | |

| that | clear | is | that | Marie the new chairman | becomes | |||

| 'that it is clear that Marie will be the new Chair.' | ||||||||

| b. | dat | Jan niet | gemeld | heeft | [dat | hij | weg | zou | zijn]. | direct object | |

| that | Jan not | reported | has | that | he | away | would | be | |||

| 'that Jan hasnʼt reported that heʼd be away.' | |||||||||||

| c. | dat | Peter erover | klaagt | [dat het regent]. | prepositional object | |

| that | Peter about.it | complains | that it rains | |||

| 'that Jan is complaining about it that it is raining.' | ||||||

A typical example of fragment clauses is given in (13b); constructions like these are arguably derived by a partial deletion of the phonetic contents of a finite clause, which is indicated here by means of strikethrough.

| a. | Jan heeft | gisteren | iemand | bezocht. | speaker A | |

| Jan has | yesterday | someone | visited | |||

| 'Jan visited someone yesterday.' | ||||||

| b. | Kan je | me ook | zeggen | wie | Jan gisteren | bezocht | heeft? | speaker B | |

| can you | me also | tell | who | Jan yesterday | visited | has | |||

| 'Can you tell me who (Jan visited yesterday)?' | |||||||||

Wh-extraction is illustrated in (14b) by means of wh-movement of the direct object of the complement clause. In constructions like these the wh-phrase arguably originates in the same position as the direct object dit boek in (14a), that is, the embedded clause in (14b) contains an interpretative gap, which we have indicated by means of a horizontal line.

| a. | Ik | denk [Clause | dat | Marie | dit boek | morgen | zal | kopen]. | |

| I | think | that | Marie | this book | tomorrow | will | buy |

| b. | Wat | denk | je [Clause | dat | Marie __ | morgen | zal | kopen]? | |

| what | think | you | that | Marie | tomorrow | will | buy | ||

| 'What do you think that Marie will buy tomorrow?' | |||||||||

Section 5.2 discusses three types of formally different types of infinitival clauses: Om + te-infinitivals, te-infinitivals and bare infinitivals. The examples in (15) are control constructions, which are characterized by the fact that they typically have an implicit (phonetically empty) subject pronoun, which is normally represented as PRO. It seems that the construal of PRO, which is normally referred to as control, is subject to a set of context-sensitive conditions. In certain specific environments PRO is obligatorily controlled in the sense that it has an (i) overt, (ii) unique, (iii) local and (iv) c-commanding antecedent, whereas in other environments it need not satisfy these four criteria.

| a. | Jan beloofde | [om PRO | het boek naar Els | te sturen]. | om + te-infinitival | |

| Jan promised | comp | the book to Els | to send | |||

| 'Jan promised to send the book to Els.' | ||||||

| b. | Jan beweerde [PRO | het boek | naar Els | te sturen]. | te-infinitival | |

| Jan claimed | the book | to Els | to send | |||

| 'Jan claimed to send the book to Els.' | ||||||

| c. | Jan wilde [PRO | het boek | naar Els | sturen]. | bare infinitival | |

| Jan wanted | the book | to Els | send | |||

| 'Jan wanted to send the book to Els.' | ||||||

In addition to the control infinitivals in (15) there are also subject raising and accusativus-cum-infinitivo infinitivals. An example of the first type is given in (16b). The fact that the matrix verb schijnen in (16a) is unable to take a referential subject such as Jan suggests that the same holds for the verb schijnen in (16b). This has led to the hypothesis that the noun phrase Jan in (16b) is base-generated as the subject of the infinitival clause and subsequently raised to the subject position of the matrix clause, in a similar way as the underlying object of a passive clause is promoted to subject, subject raising is restricted to te-infinitivals and bare infinitivals and we will show that this can be accounted for by appealing to a generally assumed locality restriction on this type of passive-like movement.

| a. | Het | schijnt | [dat | Jan een nieuwe auto | koopt]. | |

| it | seems | that | Jan a new car | buys | ||

| 'It seems that Jan is buying a new car.' | ||||||

| b. | Jani | schijnt [ti | een nieuwe auto | te kopen]. | |

| Jan | seems | a new car | to buy | ||

| 'Jan seems to be buying a new car.' | |||||

Accusativus-cum-infinitivo (lit.: accusative with infinitive) constructions are characterized by the fact that the subject of infinitival clause is phonetically expressed by an accusative noun phrase. In Dutch, this construction occurs with bare infinitivals headed by a causative or a perception verb only; cf. example (17).

| a. | Marie | liet | [hemacc | dansen]. | |

| Marie | make/let | him | dance | ||

| 'Marie made him dance.' | |||||

| b. | Els hoorde | [henacc | een liedje | zingen]. | |

| Els heard | them | a song | sing | ||

| 'Els heard them sing a song.' | |||||

Section 5.3 concludes with a discussion of complementives, that is, clauses that function as secondary predicates; examples of cases that are sometimes analyzed as complementives are the copular constructions in (18).

| a. | Een feit | is | [dat | hij | te lui | is]. | |

| a fact | is | that | he | too lazy | is | ||

| 'A fact is that he is too lazy.' | |||||||

| b. | dat boek | is moeilijk | [(om) | te lezen]. | |

| that book | is hard/not | comp | to read | ||

| 'that book is hard to read.' | |||||

Because the complementive use of clauses is extremely rare, it seems advisable to not immediately commit ourselves to the suggested complementive analysis. Closer scrutiny will in fact reveal that at least in some cases there is reason for doubting this analysis: it seems plausible, for instance, that example (18b) should be analyzed as a construction with a complementive AP modified by an infinitival clause.

Non-main verbs differ from main verbs in that they do not denote states of affairs, but express additional (e.g., aspectual) information about the state of affairs denoted by the main verb. This implies that non-main verbs do not have an argument structure and are thus not able to semantically select a clausal/verbal complement. Nevertheless, the use of the term selection is also apt in this case since non-main verbs impose selection restrictions on the verb they are accompanied by: the examples in (19) show that perfect auxiliaries like hebben'to have' select past participles, semi-aspectual verbs like zitten'to sit' select te-infinitives, and aspectual verbs like gaan'to go' select bare infinitives. Chapter 6 will review a number of characteristic properties of non-main verbs and will discuss the three subtypes illustrated in (19).

| a. | Jan heeft | dat boek | gelezen. | perfect auxiliary | |

| Jan has | that book | read | |||

| 'Jan has read that book.' | |||||

| b. | Jan zit | dat boek | te lezen. | semi-aspectual verb | |

| Jan sits | that book | to read | |||

| 'Jan is reading that book.' | |||||

| c. | Jan gaat | dat boek | kopen. | aspectual verb | |

| Jan goes | that book | buy | |||

| 'Jan is going to buy that book.' | |||||

Verb clustering is probably one of the most discussed issues in the syntactic literature on Dutch and German, and the topic is certainly complex enough to devote a separate chapter to it. Verb clustering refers to the phenomenon that verbs that are in a selection relation tend to group together in the right periphery of the clause (with the exception of finite verbs in main clauses, which must occur in second position). This phenomenon is illustrated in (20) by the embedded counterparts of the main clauses in (19).

| a. | dat | Jan dat boek | heeft | gelezen. | perfect auxiliary | |

| that | Jan that book | has | read | |||

| 'that Jan has read that book.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan dat boek | zit | te lezen. | semi-aspectual verb | |

| that | Jan that book | sits | to read | |||

| 'that Jan is reading that book.' | ||||||

| c. | dat | Jan dat boek | gaat kopen. | aspectual verb | |

| that | Jan that book | goes buy | |||

| 'that Jan is going to buy that book.' | |||||

The examples in (20) show that verb clusters may arise if a non-main verb selects a past/passive participle, a te-infinitive, or a bare infinitive as its complement. Verb clusters may actually consist of more than two verbs as is shown in (21) by means of the perfect-tense counterparts of (20b&c).

| a. | dat | Jan dat boek | heeft | zitten | te lezen. | |

| that | Jan that book | has | sit | to read | ||

| 'that Jan has been reading that book.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan dat boek | is | gaan | kopen. | |

| that | Jan that book | is | go | buy | ||

| 'that Jan has gone to buy that book.' | ||||||

Furthermore, verb clustering is not restricted to non-main verbs: it is also possible with main verbs selecting a te-infinitival or a bare infinitival (but not with main verbs selecting an om + te-infinitival). Example (22) provides some examples on the basis of the (b)-examples in (16) and (17), repeated here in a slightly different form for convenience.

| a. | Jan | schijnt | een nieuwe auto | te kopen. | |

| Jan | seems | a new car | to buy | ||

| 'Jan seems to be buying a new car.' | |||||

| a'. | dat | Jan | een nieuwe auto | schijnt | te kopen. | |

| that | Jan | a new car | seems | to buy |

| b. | Els hoorde | hen | een liedje | zingen. | |

| Els heard | them | a song | sing | ||

| 'Els heard them sing a song.' | |||||

| b'. | dat | Els hen | een liedje | hoorde | zingen. | |

| that | Els them | a song | heard | sing |

In the examples in (20) and (22) verb clustering is obligatory but this does not hold true across-the-board. In some examples, verb clustering is (or seems) optional and in other cases it is forbidden:

| a. | dat | Jan | <dat boek> | probeerde <dat boek> | te lezen. | |

| that | Jan | that book | tried | to read | ||

| 'that Jan tried to read that book.' | ||||||

| b. | dat | Jan Marie | <??dat boek> | aanbood <dat boek> | te lezen. | |

| that | Jan Marie | that book | prt.-offered | to read | ||

| 'that Jan offered to Marie to read that book.' | ||||||

Some descriptions of verb clustering take it more or less for granted that any string of verbs (or rather: verb-like elements) in clause-final position can be analyzed as a verb cluster. Section 5.2.2 and Chapter 6 show that many of such cases should in fact receive a different analysis: we may be dealing with, e.g., deverbal adjectives or nominalizations. These findings are important since this will enable us to present a much simpler description of verb clustering than is found in more descriptive grammars such as Haeseryn et al. (1997). Section 7.1 will therefore start by providing some diagnostics that may help us to identify genuine verb clusters. Sections 7.2 and 7.3 discuss the intricate relation between the hierarchical and the linear order of verb clusters. Section 7.4 concludes with a discussion of the permeation of verb clusters by clausal constituents, a phenomenon that is especially pervasive in the variety of Standard Dutch spoken in Flanders.

This chapter will discuss adverbial modification of the clause/verbal projection. Section 8.1 will discuss the various semantic types of adverbial clause: the basic distinction is the one between adverbial phrases modifying the VP, like manner and certain spatio-temporal modifiers, and adverbial phrases modifying some larger part of the clause, like negation and modal modifiers. Section 8.2 will discuss the categorial status of adverbial phrase and show that there are often various options. temporal modifier, for example, can be APs (vroeg'early'), PPs (na de wedstrijd'after the game', NPs (de hele wedstrijd'during the whole game') and clauses (nadat Ajax verloren had'after Ajax had lost the game'). Section 8.3 concludes with word order restrictions related to adverbial clauses. These involves word order restrictions can be related to the semantic type of the adverbial modifiers (e.g., clausal modifiers precede predicate modifiers in the middle field of the clause), but also to their categorial type (e.g. adverbial clauses tend to occur in extraposed position).

This chapter discusses the word order in the clause. Chapter 9 starts by providing a bird's eye view of the overall, internal organization of the clause by characterizing the positions in which the verbs normally occur (the so-called second and clause-final position), by defining specific topological fields in the clause that often enter the description (clause-initial position, middle field, postverbal position), as well as the major movement operations affecting the word order in the clause (wh-movement, extraposition, various forms of "scrambling", etc). Readers who are not familiar with Dutch syntax may find it profitable to read this chapter as a general introduction to the syntax of Dutch: it presents a number of issues pertaining to Dutch which the reader will encounter throughout this study. Chapter 10 to Chapter 13 will provide a more exhaustive discussion of the various issues introduced in Chapter 9.

We conclude our study of verbs and verb phrases with a discussion of elements that can be assumed to be external to the sentence in the sense defined in Chapter 9. The clearest cases are those elements that precede the sentence-initial position like discourse particles, vocatives and left-dislocated elements.

| a. | Hé, [Sentence | wat | doe | jij | daar]? | discourse particle | |

| hey | what | do | you | there | |||

| 'Hey, what are you doing there?' | |||||||

| b. | Jan, [Sentence | kom | alsjeblieft | even | hier]! | vocative | |

| Jan | come | please | for.a.moment | here | |||

| 'Jan, please, come here for a moment!' | |||||||

| c. | Mariei, [Sentence | ik | heb | haari | niet | gezien]. | left-dislocated element | |

| Marie | I | have | here | not | seen | |||

| 'Marie, I havenʼt seen her.' | ||||||||

Clause-external elements at the right edge of the sentence are more difficult to identify, next to discourse particles and vocative, we find at least right right-dislocated elements and afterthoughts.

| a. | [Sentence | Ik | heb | haari | niet | gezien], Mariei. | right-dislocated element | |

| [Sentence | I | have | here | not | seen | |||

| 'I havenʼt seen her, Marie.' | ||||||||

| b. | [Sentence | Ik | heb | Mariei | niet | gezien]; | mijn zusteri. | afterthought | |

| [Sentence | I | have | Marie | not | seen | my sister | |||

| 'I havenʼt seen Marie—my sister.' | |||||||||

In the volumes on noun phrases, adjective phrases and adpositional phrases we included a separate discussion of the syntactic uses of these phrases, that is, their uses as arguments, modifiers and predicates. This does not seem to make sense in the case of verb phrase. The use of clauses as arguments and complementives is discussed in Chapter 5, and their adverbial use is discussed in Section 8.3. Clauses can also be used as modifiers of nouns; such relative clauses are extensively discussed in Section N3.3. Furthermore there is an extensive discussion on the attributive and predicative use of past/passive participles and so-called modal infinitives in Section A9. In short, since the addition of a separate discussion of the syntactic uses of verb phrases would simply lead to unwanted redundancy, we do not include such a discussion here but simply refer the reader to the sections mentioned above for relevant discussion.

- 1981Intransitive verbs and Italian auxiliariesCambridge, MAMITThesis

- 1986Italian syntax: a government-binding approachnullnullDordrecht/Boston/Lancaster/TokyoReidel

- 1997Algemene Nederlandse spraakkunstGroningenNijhoff

- 1984Transitivity. Grammatical relations in government-binding theorynullnullDordrecht/CinnaminsonForis Publications

- 1989Locational verbs as unaccusativesBennis, Hans & Kemenade, Ans van (eds.)Linguistics in the Netherlands 1989Dordrechtnull111-122

- 1978Impersonal passives and the unaccusative hypothesisBerkeley Linguistics Society4157-189